Zhang Zhaosong of the Republic of China | Travel Notes of Hengyue in 1919

Publish Time:

2025-03-18 11:19

Source:

In June 1919, Zhang Zhaosong, a literati of the Republic of China, traveled from Beijing to Hunyuan via Datong to tour Hengshan Mountain, as part of his journey to visit all five sacred mountains. Before his trip, he consulted historical records, confirming that Mount Heng (North Mountain) was located in Hunyuan, Shanxi, and not Quyang, Hebei, before packing his bags and setting off on his journey, writing the travelogue "Hengyue Youji".

Editor's Note

In June 1919, Zhang Zhaosong, a literati of the Republic of China, traveled from Beijing to Hunyuan via Datong to tour Hengshan Mountain, as part of his journey to visit the Five Great Mountains. Before his trip, he consulted historical records, clarifying that Mount Taihang was located in Hunyuan, Shanxi, and not in Quyang, Hebei, before setting off on his journey and writing "A Trip to Hengshan Mountain." "A Trip to Hengshan Mountain" was included in the "New Travelogue Collection" (Volume 15), published by the Commercial Press in May 1921. This article is reprinted from the fifth edition of the "New Travelogue Collection" from August 1928. Travelogues of modern figures visiting Hunyuan and Hengshan Mountain have always been a focus of this journal; we now publish this article for our readers.

A Trip to Hengshan Mountain

By Zhang Zhaosong

(1919)

Zhang Zhaosong (1867—1950)

Zhang Zhaosong (1867—1950), courtesy name Jingzhai, hao Jingzhai, was a native of Hepu, Guangxi, and a former Qing Dynasty scholar. In the first year of the Republic of China, he went to Beijing and was hired by Yuan Shikai as a home tutor, teaching many of Yuan's daughters, grandsons, and granddaughters, and also lectured at the Beijing Tax School and the Military Academy. During the sixth and seventh years of the Republic of China, he went to Anyang, Henan to lecture, taking the opportunity to explore the ancient sites of Zhongzhou, touring the Five Great Mountains and leaving behind poetry and prose.

In the fourteenth year of the Republic of China, Li Jishen established the Zhongyuan Library in Guangzhou to commemorate his teacher Deng Keng (Zhongyuan). Zhang Zhaosong served successively as the chief preparatory officer and director of the library. His works include "Yanjing Jiyou," "Luzou Shengji Ji," "Neizi Huang Jun Shu Zhai Liu Zhi Jia Yi Dan Qi Shou Yan," "Five Great Mountains Travelogue," "You Changping Mingling Ji," and "Zhongyuan Library Catalog, First Edition." Apart from individual publications, Zhang's works were also reprinted in various anthologies, making him famous for a time.

A Trip to Hengshan Mountain

I had visited Mount Tai and Mount Song in the autumn of Bingchen and Dingsi years. Thinking of visiting Hengshan Mountain, some said it was in Quyang, others said Hunyuan, with conflicting accounts. In the summer of Yi Mao, I took my young son Rìyuán out of Juyongguan and the Great Wall, arriving at Zhangjiakou, and traveled west to visit Hengshan, but the difficult journey stopped me. In recent years, I have frequently traveled between Baoding and Zhengding, looking west at the peaks, suspecting the presence of Hengshan. I often asked the locals, but none knew. I consulted Gu Tinglin's "辨北岳" (Discerning Mount Taihang): "Ancient emperors’ offerings did not always take place at the mountain’s peak. The offering to Mount Taihang in Shangquyang was 140 li from the foot of the mountain. Hengshan County spans 300 li. When emperors received feudal lords, it would be at a flat area in the south of the mountain, not a dangerous, remote, and isolated area. Therefore, I went to Quyang first, and then climbed Hunyuan.". Gu Tinglin used the word “went” for Quyang, not “climbed,” showing that he was referring to the temple for offerings, not the mountain peak in Hunyuan.

Wei Yi Jie’s preface to "Quyang Zhi" also states: "The worship of Mount Taihang Temple in Quyang has been around for a long time. Hunyuan is the peak of Hengshan Mountain, and Damo is the main branch. From Hunyuan, the mountain range reaches Quyang via Feihux, convenient for hunting and court visits. They did not want to make the horses and carriages climb the mountains and valleys, thus sparing manpower." "Hunyuan Zhi" also states: "Hengshan Mountain is 30 li south of the state capital, connected to Yuhua Peak in the north, Baishan in the east, and Qiangfeng Ridge in the southeast. The mountain range enters Shuoping from the Yinshan Mountains in the north, goes through Shuozhou, turns west and east to become Gouzhu. It continues to Xiawu, Ruyue, Shuya, and Cuiwei, rising in the south of the state, becoming Hengshan Mountain, with the peak being Tianfeng Ridge. Below it is the North Mount Taihang Temple, built in the first year of the Northern Wei Dynasty’s Taiyan era, and repeatedly rebuilt during the Tang Dynasty’s Wude era, the Jin Dynasty’s Tianhui era, and during the Ming Dynasty’s Hongwu era. During the Hongzhi era, Liu Yu, considering the old temple too narrow, built temples and palaces on the sunny side of Zhongfeng, changing the old temple into a寝宫. It connects to Damo Mountain in Fuping for more than 300 li, extending southeast to Quyang." Considering these accounts, they all accord with Gu’s statement, further showing that the peak of Hengshan Mountain should be in Hunyuan, not in Quyang.

Cover of "New Travelogue Collection"

Only Li Yunlin's "A Trip to Mount Taihang" states that Mount Taihang is in Quyang. Traveling to Baoding, upon viewing the mountain he found the main peak. Arriving at the Mount Taihang Temple, he asked a porter about the peak, who replied, "That’s Baishi Mountain." Following his words, he walked tens of li to the foot of the peak. He climbed, finding the path not too steep, and within ten minutes, he reached the summit. Descend from the shady side of the peak, he walked about 20 li and reached Guangchang County. Returning, he wrote an account, believing he had climbed the summit of Hengshan (Li Yunlin's account is found in "The Essence of Ancient and Modern Novels," Geography, Mountains and Rivers).

I note that Gu Zuyu’s "Fangyu Jiyao," citing "Baoding Prefecture Records," states that "from Tang County north to Yizhou is all Hengshan Mountain;" and also cites "Guangchang County Records," stating that "Baishi Mountain is 20 li southeast of the county seat, facing Heishi Mountain." It does not explicitly identify Baishi Mountain as Hengshan Mountain. Hengshan Mountain has many other names; "Erya" states: "Mount Taihang, the Han Dynasty changed its name to Changshan to avoid Emperor Wen’s name." "Baihu Tong" states: "North is Heng, meaning constant. Yin ends, Yang begins, its path long, therefore called Changshan." "Shangshu Datuan" states: "Hongshan," Ge Hong’s "Pillow Book" states: "Mount Taihang is also called Hengzong, Mingyue, Maodu." "Shui Jing Zhu" states: "Mount Taihang is also called Yin Yue, Zi Yue, and Zhen Yue in the Tang Dynasty's Yuanhe era. The Song Dynasty avoided the emperor’s name Zhenzong, therefore it was often called Changshan." "Fuping Records" states: "Damo Mountain is a ridge of Hengshan Mountain, also called Shenjian. Additionally, there are Lantang Mansion, Lie Nu Palace, Huayang Terrace, Ziwei Palace, Taiyi Palace, Qingfeng Tuo, and the Yuan Jin Cheng Hu Di, all found in "Kuangdi Zhi." Ultimately, there is no reference to it being called Baishi Mountain. Now, Li actually considers the Baishi peak he climbed to be the summit of Hengshan Mountain, though it may be a branch of Hengshan Mountain. However, judging from the porter’s words, it is close to empty conjecture. How can it be credible? This is why I decided to visit Hengshan.

Table of Contents of "New Travelogue Collection"

On the ninth day of the sixth month of the lunar calendar in the year Ji Wei (己末), I took an early train from the capital via the Beijing-Sui Railway and then went to the Ju Tang Pass section of the Great Wall. I passed Zhangjiakou at noon and arrived at the East China Inn in Datong in the evening. I hired a servant and rented two horses (each costing one silver dollar per day, and the servant's wages and food cost fifty cents). The next morning, the servant guided me on horseback through the three main streets of Datong's inner, middle, and outer cities. This was the place where Tuoba Gui of the Northern Wei Dynasty established his capital. I saw the offices of the Northern Jin Garrison Commander, the Yanmen Pass Prefect, and the County Magistrate. Merchants and people lived together; the shops mostly sold local goods. The furs on display were quite eye-catching. The streets were narrow and dirty, and the old houses were uneven. The inner and outer cities showed signs of gradual decay. Women in the streets gathered by the doors, sitting on the ground, exposing their chests to cool off. Some had elaborate hairstyles and painted lips and carefully dressed feet, others rode donkeys or horses, holding their children. Their movements were lively, and their voices were loud; they wore short jackets and pleated skirts. The language of the officials and the habits of the townspeople were the same. The men were dark-skinned and had prominent cheekbones; they were fierce and quick, having their own unique northern frontier style. Going out through the southeast gate, the suburbs were flat and open. I crossed the Yu River, where the mud was deep and the water flowed sluggishly. After the rain, dry riverbeds were visible. The weather was extremely hot, and there were few trees along the way. I rested for a while at the Sierzhuang National School. More than ten children, along with a teacher, were gathered in a flat-roofed earthen house. On a low platform, there was an altar to Confucius, with two earthen kangs (heated beds) on either side, covered with reed mats. The children were all sitting cross-legged, facing the wall, each in front of a desk and cabinet, with inkstones and books, quietly listening to the teacher's instructions. The teacher asked a child to go to the kang to boil tea and serve a drink. The coal smoke seeped through, and escaped from another hole. A cool breeze came in through the sparse curtains, the ground was dry and clean, and there were few flies. I asked about other schools in the area and how they compared to this one. He replied that they didn’t have much funding; the monthly public funds of about ten or more silver dollars were enough, and they didn’t charge students tuition, so there wasn’t much difference between them.

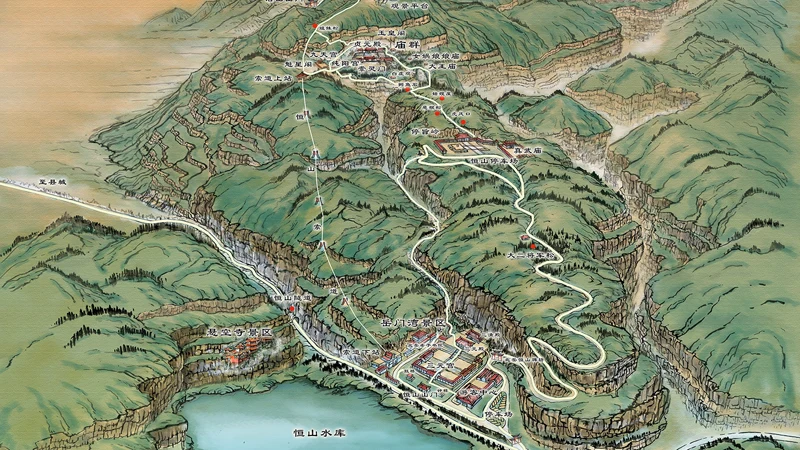

New Travel Notes Collection, Volume 15, Shanxi, Hengyue Travel Notes - Part Four

After leaving, I continued on. I passed Wangjiazhuang and Zhoujiabao and crossed the Sanggan River. Along the way, the plains were covered with fields. In every village I passed, I saw old Lama temples, very few trees, and almost no ponds. I heard that they relied on deep wells to provide water. Most of the farmers were men, weeding under the sun. The midday sun was extremely hot; approaching the southern foot of the mountain, I stopped at Jijiazhuang. From Datong to here, it was about sixty more li. The next morning, I climbed Mount Ailao, also known as Hengshan, which contains the passage through northern Dai. The cliffs reached the sky, as if carved by ancients. The coal cliffs were steep and winding; fine soil and sand occasionally fell from above, making a rustling sound like a stream. The path wound upwards; some people used three or four animals to pull a cart and walked up the trail. Hills and ridges were layered, villages scattered among them; the rocky crevices and mud trails were covered in lush greenery. After about twenty li, we reached the top of a ridge called Songshuwang in the local dialect, where there was a small shop, where we rested for a while. A mountain man pointed east and said: "That towering mountain is Hengshan." We wound our way down the mountain. The steep slope was rugged. We passed Yituo Primary School, rested for a while in Sanlingzhai. Continuing on, we passed over the Hancunbao Bridge and Jian River; a thunderstorm approached, so we hurried to the county town of Hun Yuan, just as the noon cannon fired. From Songshuwang to here was about forty more li. I stayed at a shop named Tianqingchang run by a man surnamed Xu in the South Gate.

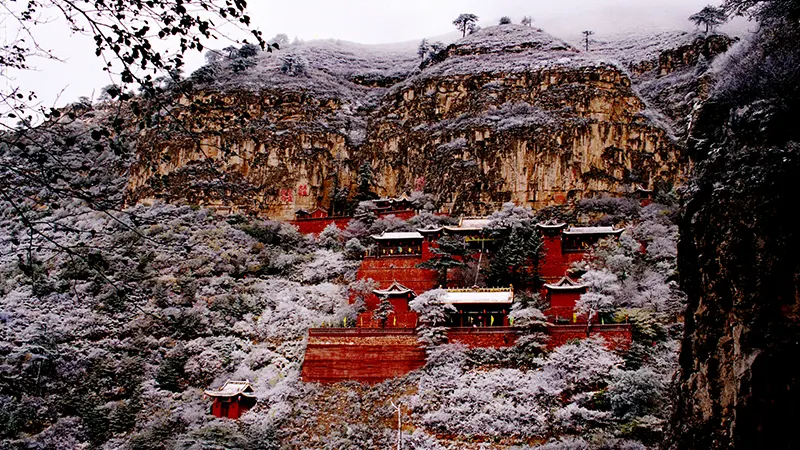

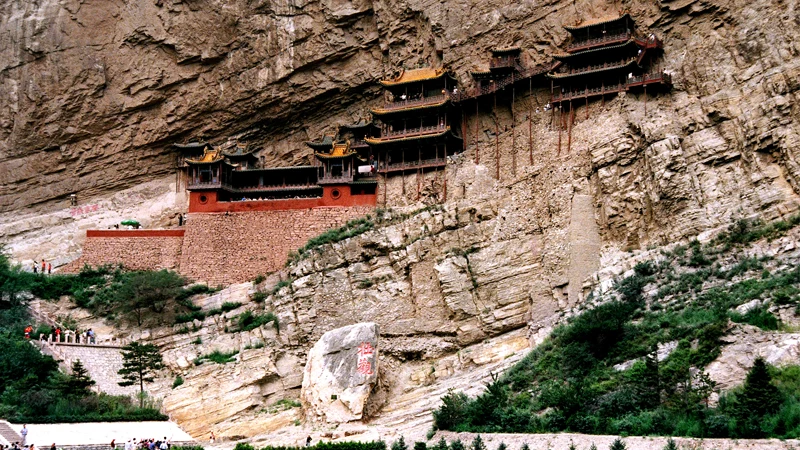

A sudden downpour caused the mountain streams to swell. I heard they were several feet deep. After bathing in the evening sun, I walked into the town. I went to Cheng's bookstore to borrow the Hun Yuan County Annals and a map of Hengshan Mountain, but they didn’t have either. I heard that Hun Yuan was poor and had few resources; although coal was abundant in the mountains, its value was low and transportation was inconvenient, making it difficult to sell. Fortunately, the local customs are simple, and the people live peacefully, working and studying. Women’s education is developing, with more than thirty women graduating from normal schools, promoting education and keeping up with the men's schools. In terms of water conservancy and agriculture, officials, gentry, and common people are now working together to get things started. I returned to the Xu's shop to spend the night. The next morning, Mr. Xu had already purchased supplies for climbing the mountain, such as tea, noodles, sugar, and warm clothes, which were packed into bags and loaded onto a strong donkey. Together with his younger brother Jizquan, he led me on horseback. We climbed east into the gorge and saw the cliffs, on which were carved the words "Magnetic Kiln Dangerous Pass." The stone peaks were tall and close together, soaring into the clouds, looking like layers of stacked stages or galleries. There were square holes at the base, one on each side, which were said to be the supports for old beams that held back the rising water; long since abandoned. On the south wall there was the Hanging Temple and a plaque that reads "The High Mountain is a Goal." Next to it was a stone on which Li Bai's inscription "Magnificent View" was carved. It seemed like a beehive and swallow's nest, called "Yueyuan Gate," which was said to be the place where Yang Ye guarded the three passes.

New Travel Notes Collection, Volume 15, Shanxi, Hengyue Travel Notes - Part Five

Following the stream, the sound of hooves and waterfalls echoed. Coal mines appeared repeatedly, and transport animals were everywhere; the morning air was refreshing and cool enough to warrant wearing cotton clothing. After about twenty li, I suddenly saw mountains surrounding us, slightly spread apart, like another world. Above stood a memorial archway with four large characters, "Hengshan Mountain," rebuilt in the sixteenth year of the Hongzhi reign (Ming dynasty), and inscribed by Liu Yu. In front were archways rebuilt by officials and gentry in the early Guangxu reign and in the sixth year of the Republic of China, with inscriptions such as “Divine Power Supports the Mandate of Heaven” and “Shield of Yan and Jin,” each with two iron or stone beasts. To the left, there was an inscription from the Daoguang reign on the rebuilding of the Yue Temple, reading "The First Mountain of Northern China." To the right were tablets with the texts of imperial sacrificial offerings to the Yue Temple from the Ming and Qing dynasties; all grand and imposing. To the north were the San Yuan Palace, the Lama Temple, and the Bai Yi Temple; all small and neglected, with few monks and Taoists. We went north up the steep cliff; the path was winding. The guide galloped ahead, and the horse was steady; I realized that it was a good steed from northern Hebei. I hadn’t realized how long the gorge was until now, suddenly surprised to see it was beyond the reach of ordinary horses. After climbing for three or four more li, we arrived at Tingzhi Ridge, where there was a Dragon God Temple, which was called the "Beginning of the Cloud Road." Several pine trees stood tall and straight, gazing up at the top, densely clustered, unlike those seen at Taishan Mountain; they were like old, twisted shapes.

After walking for about three li, we passed Cuiyun Pavilion. To the east is Wangxian Ridge, next to which is Jixian Cave, silent and deserted. To the northeast is Zizhiyu, which the Jiajing Emperor ordered to be searched. During the rainy season, the dampness and heat created fungus, snakes, and scorpions; it was dangerous to collect anything. There was a rock in front of the ravine, naturally forming steps—a place to shake off one’s clothes. In the southwestern secluded cliff, there was a multi-colored stone fat, rich in texture and taste, rumored to be used to refine elixirs; I picked up a small piece and kept it. After more than a li, to the north, I saw inscriptions on the cliff face of two large and two small characters "Hengzong." Going west for dozens of meters, we arrived in front of a temple, next to the Hufuikou Pavilion and the "Jie Shi Tablet." The road became even more rugged; after another two li, we reached the Land Deity Temple and the Pure Yang Palace, and nearby was the Niangniang Temple. We stopped our horses here. We climbed about ten meters, passed Lingyun Pavilion, and arrived at Beiyue Temple. There was a plaque on the main hall with the inscription 'Zhenyuan'; inside, the Yue God was worshipped. There were two other plaques, one with a title by the Kangxi Emperor, reading "Blessings Endure Forever," and another one with a title by the Guangxu Emperor, reading "Unique in the Northern Wilderness." The outer gate was called "South Heavenly Gate," and to the left and right were tablets with texts of sacrificial offerings by Ming and Qing emperors, a total of twenty-nine; to the west was the Imperial Stele Pavilion.

New Travel Notes Collection, Volume 15, Shanxi, Hengyue Travel Notes - Part Six

Behind the building, on the cliff face, are large characters carved into the rock, including “Immortal's Mansion,” “Famous Mountain Under Heaven,” “Path to Heaven,” and “Majestic and Spiritual Mountain.” To the west, slightly off to the side, is the South-Viewing Four Peaks Hall, its walls and stelae inscribed with several poems. Of particular note is a poem in the style of Zhu Xiudo of the Qianlong era, written in a concise and striking manner. Ascending the slanted path for half a mile brings one to the West Peak's Qinqi Terrace. Inscribed on the terrace are the four characters “Traces of Enlightenment.” The scene is desolate and ancient; a light tap on the stones produces a resounding, resonant echo. Following the path, traces of donkeys' hooves are still visible. Reaching the East Peak, one finds the Da Mao Shan Temple, where a stele records that “Emperor Shun, during a hunting expedition, encountered a snowfall and offered a remote sacrifice; a stone flew down from the mountain and landed in front, and was given the name 'An Wang' Stone. On a later visit, the stone flew to Quyang, and he ordered a temple to be built on that spot to offer sacrifices.” This account coincides with the account of the flying stone and temple construction described in the Quyang Zhi. However, the Quyang Zhi, in its description of the sacrificial hall, further states that 'during the Tang Dynasty's Zhen Guan era, a stone fell to the west of the county and a temple was built in response, initially named Beiyue Fuzun. In the fifteenth year of Kaiyuan, it was elevated to the status of 'An Tian Wang.' This seems contradictory. Considering the story of a flying stone leading to the construction of a temple, it sounds rather improbable and hardly reliable. However, standing high and looking far, overlooking the mist-shrouded mountains and valleys, one can see a formation reminiscent of many heroes defending the heartland. This reminded me of Qiao Yu's 'Climbing the Northern Peak' account, stating that 'to the east are Yu Yang and Shang Gu, and to the west is from Datong southwards, with peaks extending to the north as far as Yunzhong, and to the south one can glimpse Mount Wutai faintly in the distance, more than 200 miles away. The Cui Ping Five Peaks, and the Huajin Fenglong Mountains, all bow their heads and lie prostrate below,' etc., which is entirely not fabricated. Recalling that the Zhao clan concealed talismans here, and having myself visited the summit of Mount Tai in the past, leaving my mark there, I now on this peak of Hengshan, standing before the Wu Xu Terrace, place a small seal I carry upon the cliff face and earnestly pray to the mountain spirit, to forever establish my presence in the north.

The soil on the peak is fertile, and the mountain people, undeterred by the dangers of the terrain, plant grains, millet, medicinal herbs, and fruits extensively on the cliff faces and crevices, spreading down to the foot of the mountain. Is this what Guan Zhong referred to as 'Hengshan Mountain, where the five grains flourish and four harvests are reaped'? This is something unseen on Mount Tai. On this day, the clouds had cleared and the heat subsided; in the afternoon, a cold breeze came up. We donned cotton jackets to ward off the chill. Descending to the 'Human Heaven North Pillar' archway, we saw the thousand-character inscription in parallel prose by Zhang Chongde of the Qing dynasty. Two lines were carved on the right side, which read:

Mid-Autumn, the clouds clear, the moonlight round, On the summit of Hengshan, all night long, we watch the moon’s light.

No palaces of jade and jasper, In this world, could match this coldness in height.

Composed while visiting Beiyue Temple on the Mid-Autumn Festival, Ding Wei year of the Qianlong era, and viewing the moon from the Qinqi Terrace.

Written by Feng Minchang of Guangdong Province.

From "New Travelogue Collection, Volume 15: Shanxi, Hengshan Travelogue" — Part Seven

I felt a profound sense of respect. Happily, it was a remaining work by Mr. Feng Yushan of our county. Below it, I too inscribed two lines: 'On the 2nd day of the 10th month in late summer of the 8th year of the Republic of China, Zhang Zhaosong of Guangdong Province visited Beiyue Temple, inscribed a poem on the imperial stele pavilion wall, and wrote this.' In remembrance of this, the heartfelt inscription on the stone took approximately two hours to coarsely carve before the ink was applied to numerous sheets of paper. I just noticed some flourishing vegetation between the rocks, which I suspect to be among the 'nineteen types of sacred herbs,' so I collected a handful and a section of pine root, storing them in my bag.

Looking up at the cliffs, a gnarled old tree, twisted and seemingly about to move, is seen. It is said to have been there for many years and is called the 'Four-Clawed Dragon.' A Taoist priest invited me back to the Chonglingguan temple for tea and a simple vegetarian meal. A wolf pelt was placed on the kang for me to rest; about an hour later, I fell into a peaceful sleep. Going east past the Baiyun Lingxu Cave, I arrived at the Tongyuan Valley, where the four seal characters 'Traces of the Immortal Guolao' were carved into the wall; these were inscribed by Xing Qiren of the Ming dynasty. It is said to be where Zhang Guolao refined elixirs, and during the Tang dynasty was bestowed with the title of 'Tongyuan Xianren.' Nearby is the Feishi Cave, a vast cave, likely formed by collapses during excavation, not by divine power. Next to the cave is the Huan Yuan Cave, a deep and dark cave; Huang Yingkun erected a stele to record when it was sealed and subsequently reopened. Before us is the Tianbao Temple, and eastwards is the Huibao Zongheng Pavilion, offering magnificent views. Walking westward through the dense pines, we reach the Li Yiquan Pavilion, where the well water is clear and sweet; this is the site of the Longquan Shangguan Temple built in the early years of the Tang Kaiyuan era, the 'Taiyuan Spring' mentioned in the 'Yu Di Lan'. Next to it is Cheng Zhi's hidden retreat, with beautifully inscribed poems and prefaces. Looking back at the White Tiger Peak and Xiyang Cliff, the mountain ridges appear verdant; it is already five o'clock. The Taoist priest presented me with two walking sticks, both forked and sturdy, the wood slightly curved, said to bestow blessings of longevity. I happily accepted them. Reaching the foot of the mountain, I rode a horse out of the canyon, returning to Xudian in the south of Hunyuan City under the moonlight. The next morning, I led my servants and horses through 130 li and arrived at Datong's station in the evening. On the fourteenth, I took the Beijing-Suiyuan Railway early in the morning, passing through the Badaling, Great Wall, and Juyongguan tunnels, heading east. In the evening, I arrived at Beijing's Xizhimen Gate and took the circular city railway to my residence in Dongzongbu Hutong.

Originally published in "New Travelogue Collection, Volume 15"

August 1928, 5th Edition

Proofreader: Xue Fang

Editor: Xing Xuelin

Keywords:

Related News

Republic of China hemp mat treasure | Guiyou (1933) Deng Hengyue Ji (with poems and texts)

In today's ancient city of Hunyuan, when discussing well-preserved ancient residences, one must mention the "Ma Family Courtyard." The original owner, Ma Xi Zhen, has also gained attention, as if the person is known because of their residence.

Republican High Liangzuo | 1935 North Shanxi Field Trip Notes

In the spring of 1935, the Nationalist Government in Nanjing dispatched Shao Yuanchong, a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang, and Zhang Ji, a member of the Central Supervisory Committee, to Shaanxi to pay homage to the Yellow Emperor's Mausoleum. After the ceremony, Shao Yuanchong went on an inspection tour of Northwest China, visiting Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi. His secretary, Gao Liangzuo, accompanied him throughout the journey, recording their observations and experiences, which were subsequently published in major newspapers and generated significant public attention.

Republic of China, Jiang Weiqiao | 1918 Hengshan Mountain photo album

In September 1918, Jiang Weiqiao, a councillor of the Ministry of Education of the Beiyang Government, was ordered by the Ministry of Education to inspect the academic affairs in Shanxi Province. He took the opportunity to pay his respects at Mount Wutai and Hengshan Mountain. He departed from Beijing on September 21, first taking a train to Shijiazhuang, and then to Taiyuan; then he took a carriage to Mount Wutai and Hengshan Mountain; and finally returned to Beijing from Datong by train on October 13.

Shao Yuanchong of the Republic of China | Brief Record of the 1935 Northern Mount Taihe Expedition

In the spring of 1935, the Nanjing Nationalist Government dispatched Shao Yuanchong, a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang, and Zhang Ji, a member of the Central Supervisory Committee, to Shaanxi to pay homage to the Yellow Emperor's Mausoleum. After the ceremony, Shao Yuanchong went on an inspection tour of Northwest China, departing from Xi'an on April 25 and subsequently visiting Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi.

Chen Xingya's Travelogue of Yungang Grottoes and Hengshan Mountain in 1935, Republic of China

Between the September 18th Incident and the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, Chen Xingya held the idle post of council member of the Peiping Pacification Commission, staying at home and often traveling with friends to various famous scenic spots in China.