Republican High Liangzuo | 1935 North Shanxi Field Trip Notes

Publish Time:

2025-03-18 12:57

Source:

In the spring of 1935, the Nationalist Government in Nanjing dispatched Shao Yuanchong, a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang, and Zhang Ji, a member of the Central Supervisory Committee, to Shaanxi to pay homage to the Yellow Emperor's Mausoleum. After the ceremony, Shao Yuanchong went on an inspection tour of Northwest China, visiting Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi. His secretary, Gao Liangzuo, accompanied him throughout the journey, recording their observations and experiences, which were subsequently published in major newspapers and generated significant public attention.

Editor's Note

In the spring of 1935, the Nanjing National Government dispatched Shao Yuanchong, a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang, and Zhang Ji, a member of the Central Supervisory Committee, to Shaanxi to pay homage to the Yellow Emperor's Mausoleum. After the sacrificial activities, Shao Yuanchong made a tour of Northwest China, visiting Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi. His secretary, Gao Liangzuo, accompanied him throughout the journey. Gao recorded his observations along the way, which were published in major newspapers at the time, causing a strong reaction. "Northwest Travel Notes" includes "A Trip to Hedong," which recounts his observations during his investigation in Shanxi.

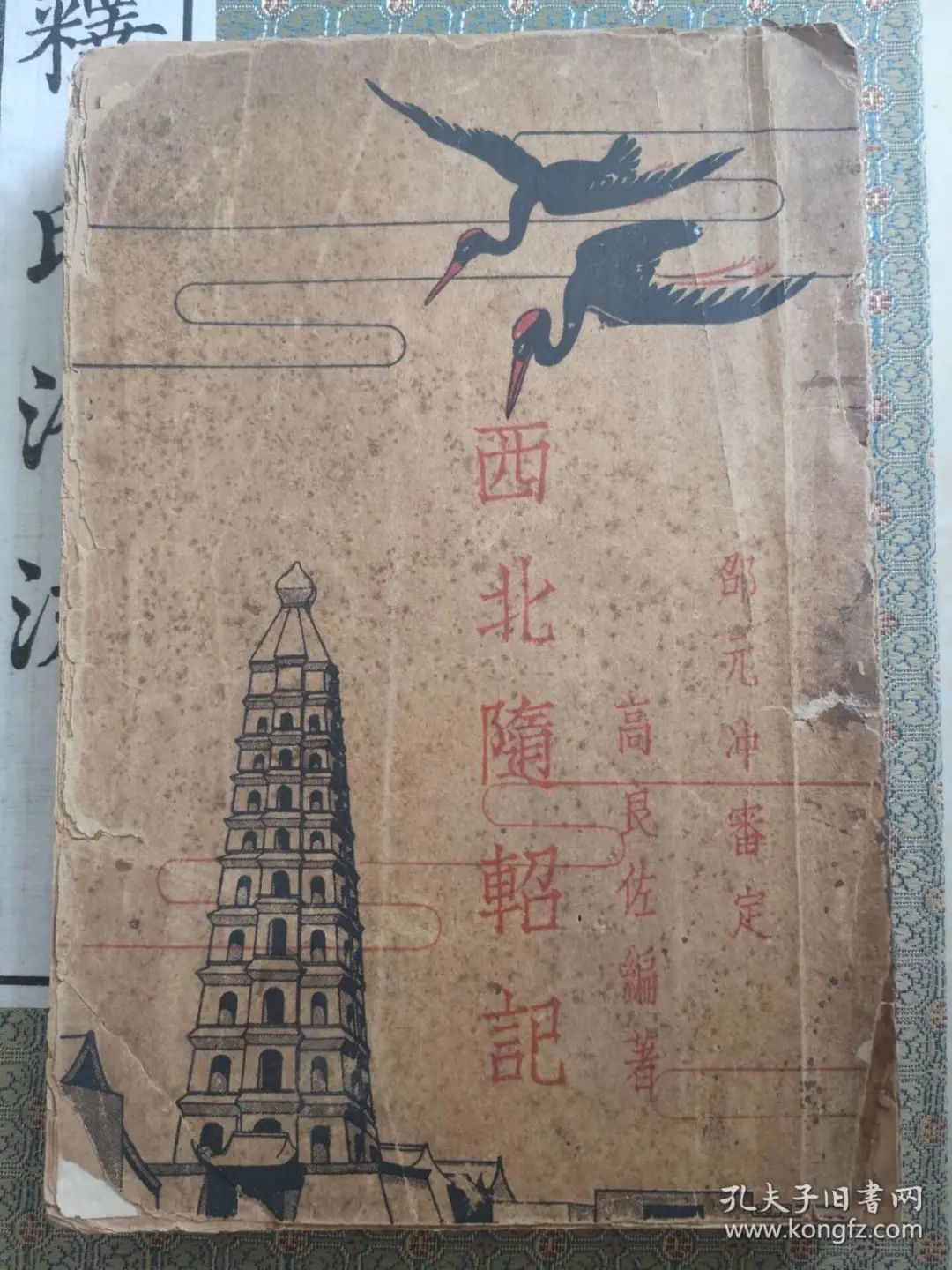

In February 1936, Gao Liangzuo compiled these factual records into "Northwest Travel Notes," which was reviewed by Shao Yuanchong and printed in Nanjing by the Jian Guo Monthly Publishing House. In August 2013, "Republic of China Shanxi Reader: Investigation Records" was published by Sanjin Publishing House, including Gao Liangzuo's account of his investigation in Shanxi under the title "Investigation Record of North and Central Shanxi." This article excerpts the parts about Datong and Hunyuan from "Investigation Record of North and Central Shanxi" and has been retitled.

Travelogues of modern figures visiting Hunyuan and Hengshan Mountain have always been a focus of this publication. We are now publishing this article for our readers.

Gao Liangzuo (1907~1968), courtesy name Mengbi, was from Songjiang, Shanghai, and served as Shao Yuanchong's secretary.

In 1936, "Northwest Travel Notes," authored by Gao Liangzuo and reviewed by Shao Yuanchong, was published by Jian Guo Monthly Publishing House in Nanjing.

Investigation Record of North Shanxi

Gao Liangzuo | Text

Inside pages of "Republic of China Shanxi Reader: Investigation Records"

1. Yungang Grottoes

July 23

At 4:00 AM, we arrived at Datong Station, where we were greeted by Zhao Chengshou, the commander of the Datong Cavalry, Lu Zhongfu, the Datong County Magistrate, and other officials and representatives. After Shao and Fu got off the train, they rested at the Shanxi Provincial Bank and had breakfast. Because of urgent public affairs, Chairman Fu left Datong for Taiyuan separately from Shao. At 9:30 AM, accompanied by Commander Zhao, we went to visit Yungang.

Yungang is located 30 li west of Datong city, at the foot of Wuzhou Mountain. The cliffs stand tall, with grottoes lined up, and viewed from afar, the rolling hills resemble a patch of clear clouds stretching across the horizon - this is the renowned Yungang Grottoes. Datong has been an important town in Yan and Jin since ancient times. During the Spring and Autumn Period, it was inhabited by the Northern Di tribes; during the Warring States period, it belonged to Zhao and Qin, and was the land of Yunzhong County. During the Han, Wei, and Jin dynasties, it was Pingcheng County of Yamen County. Emperor Daowu of the Northern Wei Dynasty moved the capital to Pingcheng, building palaces, ancestral temples, and shrines, on a large scale. During the Tang dynasty, it was Yunzhou, and the Datong Military Jiedushi was established. During the Liao and Jin dynasties, it was the Western Capital Datong Prefecture. During the Yuan dynasty, it was Datong Road. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, it was a prefecture, and now it is a county.

The Yungang Grottoes were excavated when the Northern Wei capital was in Datong. The stone of Wuzhou Mountain is mostly granite, highly suitable for carving. As it was close to the Wei capital, Emperor Wencheng, who was devout, ordered the construction of grottoes and Buddha statues, creating a magnificent sight. At that time, court officials who opposed Buddhism, such as Cui Hao, had already been executed. Therefore, the Emperor ordered the eminent monk Tan Yao to carve grottoes and statues in Wuzhou Mountain.

…

Traveling west from Datong along the Wuzhou River, the river water was muddy and surging, and we often saw people and animals crossing the river. Five li away, we reached Guanyintang Temple, where there is a three-dragon wall in front of the hall, said to be from the Ming Dynasty. After crossing the Wuzhou River again, we entered the pass, and after about 25 li, we arrived at the Yungang villa. It was already 10:45 AM, so we rested for a while and then visited the various grottoes. To the west of the villa, there is a towering multi-storied building, protecting the outer part of the ridge. Its blue tiles and magnificent eaves attracted our attention. This is what is now called the Shiku Temple, also known as the Dafo Temple. The temple has two grottoes, each with a three-story building, and the third floor has connected corridors. The first grotto is commonly known as the Great Buddha Hall. The hall is quite cold inside. After exiting the grotto, it was so dark that we could not see. A temple monk lit incense to illuminate the grotto, and we saw that the four walls were full of small Buddha carvings, and the colors were still vibrant. The central large Buddha is 60 meters high, majestic and splendid. We climbed to the third floor to reach the head of the Buddha. The first grotto is also known as the Tathagata Hall. In the center of the hall is a square pillar with standing Buddhas on all four sides, one of which is damaged. The carvings around the pillar are extremely delicate. On the third floor are four seated Buddhas, and there are numerous reliefs on all sides, all of which are Buddha images and floral decorations. Among them are extremely exquisite ones.

Between the Great Buddha Temple and the Five Buddha Cave, there are two grottoes: the Maitreya Hall and the Fulai Cave. In front of the Maitreya Hall, there is an inscription that reads "The First Mountain from the West," inscribed by Ma Guozhu in the fourth year of the Shunzhi reign. In the hall, there are two Buddhas sitting opposite each other on the main wall, appearing to be discussing scriptures. Above them are three Buddha images. On the east and west walls, there are eight niches each, and each niche has different decorations, either with round curtains half-hanging or with fluttering embroidered ribbons. Everything is soft and round, without the hardness of stone carvings. The celestial maidens and lotuses on the top wall are the most complete. Each lotus is surrounded by half-naked celestial maidens, separated into six parts by carved pillars. The pillars are also filled with carved celestial maidens, each with a different pose, all extremely elegant and graceful. The ingenuity of its design and the greatness of its craftsmanship are rarely seen in the world, except for the murals in the Dunhuang Mogao Caves. The Fulai Cave is west of the Maitreya Hall, and it has been greatly damaged. Observing its structure, it seems to be similar to the Maitreya Hall, except that it does not have a rear hall and is smaller. The central Buddha has been repaired by later generations with colored clay, greatly altering its original form. On the left and right of the cave entrance, one is a five-headed Buddha and the other is a three-headed Buddha, both majestic and solemn, acting as guardians and pillars. On the outer walls of the cave, there are still remnants of reliefs, but they are badly eroded and difficult to distinguish.

To the west of the Five Buddha Caves are six large caves. The easternmost cave is divided into three sections, its structure quite similar to the Great Buddha Hall. In the center is a large Buddha, more than fifty zhang high, which is still intact. The rear wall is low and damp, and the statues are severely damaged. The relief carvings in the front cave have all been defaced, with only a few retaining their original form. The second cave to the west has a similar structure to the previous one. The large Buddha has been destroyed, and there is much new decoration and color. Only the celestial maidens and standing Buddhas in the high places still retain the atmosphere of the Northern Wei Dynasty. Further west is the third cave, which is smaller inside and similar in structure to the Tathagata Hall. In the center is a square pillar, with a Buddha carved on each side. All four walls are newly decorated, and the original relief carvings have been completely removed by colored clay, which is a great pity. Further west is the fourth cave, which is larger and has two sections. The outer section has four tower-shaped pillars, which are extremely elegant and have not lost their original form. The inner section, however, has been completely painted over and remodeled. The central Buddha niche was originally divided into two levels, the upper level with three Buddhas and the lower level with two seated Buddhas. Now, only two clay Buddhas remain on the upper and lower levels. Further west, the fifth cave also has a large Buddha, about fifty zhang high, sitting cross-legged. The four walls are newly made clay statues, which are not worth seeing. Further west is the sixth cave, the interior of which has been completely destroyed and is empty. Only the relief carvings inside the cave entrance remain. Outside the cave, there are many small niches, and there are still very complete Buddha statues. The elegance and grace of their sitting postures are rarely seen in these caves, but unfortunately, many of their heads are missing, which is a great pity.

To reach the caves west of the Five Buddha Caves, one must exit the Great Buddha Temple and go around the outer wall of the Five Buddha Caves to reach the cave entrances. However, most of them have become residential areas, with earthen walls separating them. One must knock on the door to enter and get a glimpse of them. Many Buddha statues are exposed to the outside. West of this, the first large cave is also the Great Buddha Cave. Inside the cave is a large Buddha, about sixty zhang high. One can already see its shoulders and head from afar. The relief carvings on the walls are also vaguely discernible. The cave entrance is blocked by an earthen wall, so one cannot enter. To the east of the cave are two small caves. In one, two Buddhas are sitting opposite each other discussing scriptures, but it is in a state of disrepair. In the other, the cave entrance is blocked, and one can only vaguely see the colorful and ancient relief carvings inside the cave. The several-zhang-high wall outside the cave is full of small Buddha statues, countless in number. The greatness of the work is breathtaking. The second large cave to the west also has residential buildings in front of it. The central large Buddha is also about sixty zhang high. There are two Buddhas on the two walls, one standing and one sitting. The canopies above the two Buddhas are wonderfully carved, like the boxes in a theater. The relief carvings on the three walls are also very well preserved. Further west is the third large cave. The central large Buddha is a standing statue, about seventy zhang high, with a majestic appearance. Countless small Buddhas are carved on its kasaya, all extremely fine. There are four standing Buddhas on either side. The statues between the two standing Buddhas on the east wall are extremely handsome, with red kasayas that are still bright and vibrant. On the west wall of the cave entrance, there is a stone inscription that reads: “Da Ru Gu…”. Each line has about ten characters, and there are about twenty lines in total. Only twenty characters are now discernible. However, it is extremely important. Da Ru Gu refers to the Rouran people, who came to Yungang to pray for blessings during the Wei Dynasty. Further west is the fourth large cave, which is the most severely damaged. The large Buddha, from its feet to its top, is about seventy zhang or more, the largest of all the Buddhas. However, it is exposed to the elements, which is a great pity. Further west is the fifth cave, which also has a large seated Buddha. There is a standing Buddha on each of the east and west walls. The Buddha on the west wall has been destroyed. From here westward, to Bixia Palace, the caves and niches are smaller, but the countless large and small Buddhas, in various sitting and standing postures, each have their own charm.

After a hurried visit, I returned to the villa and then went east, entering the first large cave. It was dark, damp, and foul-smelling. In the center was a large Buddha, seated, about sixty zhang high. Two large attendant Buddhas stood beside it, their lower bodies having been peeled away, but their upper bodies were as good as new, beautiful and majestic, seemingly surpassing the large Buddhas in the Great Buddha Temple and the Five Buddha Caves. Further east was the second cave, half-blocked with mud. It is said to be where Liu Xiaobiao translated scriptures. Further east, passing several caves, some sealed and some open, the open ones had many damaged and peeled stone Buddhas, suspected to have been knocked off and stolen. The easternmost cave is the border between the left cloud and Yungang entrance. Having visited here, the great art of thousands of years has been fully appreciated. However, due to time constraints, I could not examine them in detail and was not satisfied.

At 1 pm, I returned to the city and had lunch at Zhao Commander's residence. At 5 pm, I went to Yanghe Street to see the Nine Dragon Wall. This wall was originally a screen wall of a Ming Dynasty Prince's mansion, built in the ninth year of Hongwu. Now the Prince's mansion has been changed into Xuandu Temple. The wall stands tall in the street, about five zhang high and twenty zhang wide, built of glazed bricks and tiles. There are countless small dragons on the small tiles, each with a different posture. It is said that there are a total of 1,380 large and small dragons, their scales and claws vivid and their colors bright and colorful, extremely exquisite. In front of the wall is a small pool, and beside it are steles recording repairs from the Qianlong and Jiaqing dynasties. Then I visited Huayan Temple on Qingyuan Street. The temple was built in the seventh year of Liao's Chongxi era, commonly known as the Upper Temple. In the eighth year of Qingning, it was expanded and housed copper and stone statues of various emperors. In the third year of Ming Hongwu, it was changed into Dayou Cang, and then Buddha statues were placed there, which are now damaged. Entering the temple gate, a tall platform rises several zhang high, with a Great Hero Hall built on top, also of similar height. The structure is simple, and the four walls are painted with Buddhist stories, extremely fine. The Buddha statues are very beautiful, with jeweled clothes, flowing skirts, and perfectly positioned hands and feet. Their eyes are long, their noses straight, their shoulders broad, and their waists slender, giving them a majestic and compassionate appearance. The five Buddhas in the center are Baosheng in the south, Amitabha in the west, Vairocana in the center, Akshobhya in the east, and Accomplishment in the north. They sit cross-legged with their eyes downcast and their hands clasped. In front of each is an attendant, and behind them are layers of flames, extremely magnificent and gorgeous. Not far from the Upper Temple is the Lower Huayan Temple. The two temples were originally connected, but they were separated in the Ming Dynasty and named the Thin Bogajiao Zangdian. The main hall is smaller than the Upper Temple and is a place for storing scriptures. There are wall scriptures on the four walls. Behind the large Buddha's seat hangs a five-room celestial palace, also a Liao Dynasty building. There are dozens of Buddha statues, which are also extremely beautiful. After lingering for a long time, I returned to my residence. I plan to leave Datong tomorrow morning and go to Hengshan Mountain.

II. Hengshan Mountain

July 24

At 6:00 AM, Commissioner Shao left Datong for Hunyuan, planning a trip to Hengshan Mountain. Departing from the southeast gate in a carriage, the journey led through open suburbs and across the Yu River. The Yu River was formerly known as the Hun River, later changed to Yu River. The "Jin Records" mention a Yu River in Datong, similar to the Hun River, now called the Yu River. Its source is the Hulu Sea beyond the Great Wall, entering through the Zhenqiang Fortress waterway, and flowing south past the Kaishangkou River, Xiaosi River, and Zhenchuan River. It passes east of the city, joins the Wuzhou River, flows south into the Sanggan River, meandering and never drying up throughout the year. Outside the city, there used to be Xingyun Bridge spanning the river, built during the Jin Tianhui period. However, due to strong currents and repeated collapses through the ages, it was finally destroyed by a flood during the Qing Jiaqing period and was never rebuilt. Traveling east after crossing the river, the weather was extremely hot, with little shade along the way. After traveling 45 li, we reached the Luozhen camp, located near the District Chief's residence. At 12:50 PM, we continued, passing the Sanggan River at 2:20 PM. The road continued across plains, with extensive farmland. In the villages passed, we saw many old Lama temples, scarce trees, and no ponds. It was said they relied on deep wells for water. At 7:00 PM we crossed the Hun River on horseback and at 8:30 PM arrived in Hunyuan County. We rested briefly at the North Gate, then were hosted by the county government, and finally stayed at Hengxing Bank in the West Gate.

From the east of the Guancen Mountain, running through Gouzhu, Yanmen and other mountains to the southeast of Hunyuan County, a mountain range rises, forming Tianfeng Ridge, which is Hengshan Mountain. It runs south into Hebei Province, rising again north of Quyang, also called Hengshan Mountain or Damo Mountain; it is as high and majestic as its counterpart to the northwest. Travelers to the Five Great Mountains often avoid Hengshan Mountain in the north, deterred by the distance and journey, and this has continued since the Han and Tang Dynasties. The ceremonies were held in Quyang, and hence, some consider the Quyang Hengshan Mountain to be the true one, leaving the Hengshan Mountain of Hunyuan desolate for a long time. From the Song Dynasty, Hengshan Mountain was acknowledged but as the country was not unified, the north was under the Khitan, and the Baigou River was the border, the sacrifice of Hengshan Mountain was still conducted by viewing it from Quyang. The Ming Dynasty finally established the Hengshan Mountain in Hunyuan as the true one. In the sixth year of Hongzhi, Ma Wensheng proposed rectifying the ceremonies and repairing the old temple in Hunyuan, but the regular sacrifices were still in Quyang, and only in the seventeenth year of Shunzhi in the Qing Dynasty did the sacrifice to the mountain finally take place in Hunyuan. Those who ascend this mountain cannot help but feel the rise and fall of nations.

July 25th, Cloudy and Sunny

At 6:15 AM, we rode along the south gate. Before going far, we saw a continuous range of peaks, rising majestically to the sky. Streams flowed down the mountains, with streams and springs along the road. Travelers crossed them while walking.

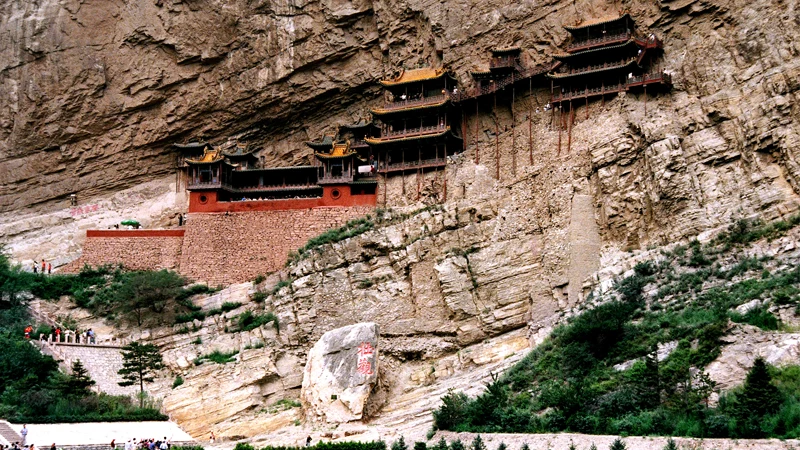

At 8:00 AM, we passed the Hanging Temple, the gateway to Mount Heng. It is backed by green screens and faces the fast-flowing water, with the sounds of waves and the beauty of mountains, all contained in one building; truly a magnificent place! The two buildings are both three stories high, built against the cliff, soaring dozens of meters high and separated by dozens of steps, connected by a suspension bridge. Looking up from below, they resemble fairy towers standing in the clouds. Climbing up, there are ornate beams and carved rafters, and exquisite architecture. It is as spacious as the Heng Building. In the middle is the Pure Yang Palace, with a statue of Lü Dongbin. On the upper floor, there are statues of the Queen Mother of the West and Laozi, as well as a niche of Maitreya Buddha, and the residence of a swordsman riding an ox, seemingly embodying the unity of Buddhism and Taoism. A clear bell rang, echoing in the clouds, making one feel like being in heaven. However, when stepping on the suspension bridge and leaning on the dangerous railings, glancing down, one's mind and eyes are shaken, and hands and feet become weak, giving a reminder of the peril of being close to a precipice. Below the cliff for a thousand feet, the Heng and Piao rivers converge, near what is called the Ci Xia. In the first year of the Tianxing era of Emperor Dao Wu of the Northern Wei Dynasty, when he conquered Yan and was returning to Pingcheng from Zhongshan, he mobilized 10,000 soldiers to excavate Hengling and construct a straight road of more than 500 li. This is the origin of the Xia. During the Song Dynasty, Yang Ye guarded the three passes and stationed his troops here. Traces of enemy towers, fortifications, cloud pavilions, and rainbow bridges still exist today. The two cliffs are steep, with the river flowing between them, so that a single soldier could block the passage, and the western Shu Yinping is not comparable. North of the temple, there is the Taibai Shrine by the Heng River, with calligraphy by Li Bai. It is said to have been built during the Southern Song Dynasty, but after searching through the steles, no evidence can be found.

From the Hanging Temple to Hengshan Mountain, there are still ten li. Going south less than half a li, there is the gate of Hengshan Mountain, with a stone archway bearing the inscription "Screen of Yan and Jin." Inside are three gates, with the inscription "Hengshan Mountain." To the left inside the gate are the Sanyuan Palace, Lama Temple, and Baiyi Temple, all on a small scale with few monks and priests.

Hengshan Mountain "Screen of Yan and Jin" archway

These four characters were written by Wang Nianzu, a Juren from Hunyuan in the Guangxu era.

Photographed by American traveler Galloway in 1925.

Entering the mountain, the road is wide and flat. There is a plain halfway up the mountain, with dozens of houses forming a village. Southwest of the mountain is the Chaimu Ridge. Above the middle of the mountain, the cliffs are steep and the roads are winding and difficult to traverse. After climbing for another four or five li, we reached Tingzhi Ridge, with a Longshen Shrine, the beginning of the cloudy road. Several tall and straight pines stand nearby. Looking up at the edge of the ridge, the pines stand densely, like coiled dragons. Going up for about three li, to the east is Wangxian Ridge, with the Ji Xian Cave nearby, deserted. To the northeast is the Zizhiyu Valley, where it is said that immortals once gathered herbs and ascended to heaven. The Jiajing Emperor once sent officials to gather herbs here, but now it is overgrown with weeds. In front of the valley is a stone, a natural staircase, called the Zhenyi Terrace. To the southwest is the Xuyang Rock, with pines and cypresses reaching high into the sky. When the morning glow touches them, the trees are brilliant with color. The cliff produces stone grease, multicolored and crystal clear; it is said that it can be used to refine pills and prepare elixirs. After another li, we could see a cliff inscription, "Hengzong," several meters long and wide, known as "Dazizwan." At Hufengkou, there is a pavilion. Behind the pavilion, on the wall, is a stele with the words "Jieshi," and to the right, it says "the auspicious day of April in the year of Yi Mao in the Hongzhi era of the Great Ming Dynasty," and to the left, "Respectfully erected by Dong Xi, Chief of the Prefecture from Huiji." From here, the road becomes even more rugged. After climbing for two li, we passed Lingyun Pavilion and arrived at the Beiyue Temple. In front is a gate, with "Forever Establishing the Hope of Jizhou" written on its front, and "Hengshan Mountain" on the back. Entering the gate is a hall, with the Ten Kings Hall to the left at the back, and then the Changing Room. To the left at the back is the Qianlong Spring, with sweet and bitter water. A pavilion was built to cover the spring, but the bitter one has since dried up. Further up, the mountain road becomes steep, impassable for carts and horses.

Entering the Yue Temple's main hall, the horizontal tablet above the entrance reads "Chongling" (崇灵). Ascending to the hall are 108 stone steps. In front of the hall are the characters "Nantianmen" (南天门), and above the hall is the tablet inscribed "Zhenyuan zhi Dian" (贞元之殿). To the east is the Qinglong (青龙) Hall, and to the west is the Baihu (白虎) Hall. The imperial throne is grand in structure. The Daoists' quarters are dusty and unfit for rest; they use the stone steps as resting places. The Daoists brew mountain tea for guests, which is quite delicious. Exiting the hall and going west, one ascends to the Wanshou Pavilion (万寿亭), an octagonal pavilion with four gates named Beiyue, Suofang, Zhongling, and Yuxiu. Inside the pavilion are four characters written by Emperor Kangxi: "Huachui Youjiu" (化垂悠久). West of the pavilion is the Yuhuang Pavilion (玉皇阁), a two-story structure housing a statue of the Jade Emperor. West of the pavilion, in a cave below, is a hall containing statues of the Three Gods of Fortune, Prosperity, and Longevity (福禄寿三星), flanked by statues of numerous immortals. The cave entrance is firmly sealed; opening it would reveal a fairyland. The pavilion and tower are situated beneath steep cliffs, with strange trees, longevity vines, interweaving and reflecting each other, interspersed with red stones and stalactites. Stelae and tablets are piled against the cliffs; though repaired over the ages, their origins can be traced back to the time of the Yao and Shun emperors. At the end of the hall are towering ancient pines and cypresses, their branches and leaves lush, offering a cool respite from the summer heat. Further up a sloping path, about half a mile, is the Qinqi Terrace (琴棋台) on the western peak, seemingly in the clouds, where one can leisurely enjoy the sound of nature. It bears an inscription reading "Wudao Yiji" (悟道遗迹), a scene of abandoned chess game, with a desolate atmosphere. Lightly tapping the chess pieces creates a sound, evoking a sense of ethereal transcendence. Following the terrace westwards, one finds a small valley, an ancient and ethereal setting, known as Tongyuan Valley (通元谷), said to be where Zhang Guolao practiced alchemy. Emperor Xuanzong of Tang bestowed upon Zhang the title of Tongxuan Xian (通玄先生), thus giving the valley its name.

At noon, I had lunch at the Yue Temple, eating noodles and porridge to satisfy my hunger. After eating, I climbed again from behind the temple to the summit. The path became steeper and more treacherous, lacking steps, obstructed by loose rocks, requiring strenuous climbing. After half an hour, I reached the top. Looking down, Hunyuan City's walls and houses looked like a chicken coop, and people were as small as black dots. The wind was so strong, it felt like I could be blown away. Yingxian Pagoda (应县浮图) loomed in the clouds, only 90 li away, seeming within reach. Gazing further east, I could see the hazy clouds of Fuyang and Shanggu. To the west, the river appeared like a screen, the Sanggan River like a ribbon. Looking north, I could see Yunzhong and Zise, and southwards Wutai and Yanmen; it was a vast and awe-inspiring panorama of heaven and earth.

After a while, having enjoyed the view, I descended. Passing an old hall, locals called it the sleeping palace, likely the Damo Shan Hall (大茂山殿). It's surrounded by pines, and the wind howled. An inscription recounts Shun's hunting expedition, where snow fell, a remote sacrifice, and a stone fell in front, hence its name "An Wang Stone" (安王石). It later flew to Quyang, leading to an order for on-site worship. To the left of the hall is Feishi Cave (飞石窟), large enough for three or four people. Its shape suggests a collapse possibly caused by digging, not supernatural removal. Next to the cave is Huanyuan Dong (还元洞), a cave of immeasurable depth, cold and dark, causing chills. Huang Yingkun, a supervisory censor during the Wanli reign, inscribed a stone tablet to commemorate its reopening. Ahead is Tianbao Hall (天宝殿), east of the Huai Bao Zongheng Pavilion (怀抱纵横亭), affording scenic views. Walking westward, through dense pines, one reaches the Lueyquan Pavilion (履一泉亭), where there is a well with sweet water. This was the site of the Longquan Shangguan (龙泉上观) temple built in the early Kaiyuan period of the Tang Dynasty, also known as the Taixuan Spring (太玄泉) as described in the Yu Di Lan (舆地览). Looking back towards Baihu Peak (白虎峰) and Xiyany Rock (夕阳岩), the mountain mist added to their beauty. It was already past three o'clock.

I walked to the foot of the mountain and rode out of the valley, returning to my lodgings in Hunyuan after four hours.

III. From Yingxian to Yanmen

July 26th

At 5 am, we departed from Hunyuan, with everyone seeing us off respectfully. At 5:40 am, we passed Yingheng Fort (映恒堡). After more than an hour, we arrived at the slightly pointed Xin Kuangkuang (辛圐圙). Xin Kuangkuang means "difficult and laborious accumulation," referring to a courtyard filled with accumulated debris; a unique word from the borderlands. From Hunyuan to this point, it's about 52 li. After this, traveling west, under the scorching sun, we sat on our cart, being roasted by the heat, making it quite difficult. After 40 li, we reached Yingxian, at noon. The county government is located in the city. Mr. Shao, a member of the commission, arranged accommodations for us at the public bank, where we rested.

Yingxian was called Guanyin County during the Han Dynasty, Guangwu County during the Jin Dynasty, belonging to Yanmen County. During the Sui Dynasty, it was changed to Shenwu, belonging to Mayi County. During the Tang Dynasty, Yingzhou was established. Later Tang upgraded it to Zhangguo Jun Jiedu. During the first year of the Later Jin Tianfu reign, it was taken by the Liao Dynasty, and it remained Yingzhou, under the jurisdiction of Xijing Road. During the Yuan Dynasty, it belonged to Datong Lu, and Jin City County was established. During the Ming Dynasty, it belonged to Datong Prefecture, with Jin City County incorporated into the state. This was continued during the Qing Dynasty and changed to a county during the Republic of China. In the southeast border, the mountain range runs east-west, connecting to Yanmen Pass, resembling a barrier. The Cuiwei Mountain (翠微山) in the southeast and Mantou Mountain (馒头山) in the southwest, both about 45 li from the city, stretch for more than 200 li, and the Great Wall follows their southern foot. To the northeast is the Longshou Mountain (龙首山), 30 li from the city, also called Bianyue Mountain (边耀山), stretching for more than 20 li. The peaks connect, echoing Yanmen Pass, thus the name Yingxian. To the northwest, the terrain is flat, with the Hunhe River and Sanggan River flowing through, fields crisscrossing, and abundant wheat crops.

In the evening, we visited the Foguang Temple (佛宫寺) to see the Sakyamuni Pagoda (释迦塔). The temple is located in the northwest corner of the city; originally called Baogong Temple, it was built by order of Tian He Shang in the second year of the Liao Qingning reign, and renovated in the fourth year of the Jin Mingchang reign. The pagoda is 360 feet high, with a circumference of half of that. It is an eight-sided, six-story structure, magnificent in scale; visible from several tens of li away as a single column standing in the sky. Each layer is over 30 feet high, with 24 pillars in the first layer, and a Sakyamuni Buddha statue on each layer. The Buddha statue on the lowest layer is about 20 feet high, sitting majestically at the base. Above the sixth layer is the Nantianmen (南天门). Looking down from the Nantianmen gate, people are as small as beans and horses as tiny as insects, inspiring awe. From the railing, one can see Hengyue, Taihang, Wutai and other northern peaks surrounding it. Above the Nantianmen are iron urns, iron dragons, lotus flowers, etc. Those who want to climb to the top to enjoy the view must climb the iron chains, which is quite dangerous. Remarkably, this pagoda is entirely made of wood, with each floor having the same area. Even after nearly a thousand years, it remains intact; hence, it is known as the number one pagoda in the world. During the Yuan Shun Emperor's reign, there was a major earthquake lasting seven days, yet the pagoda remained untouched, proving its robust construction. Yongle Emperor of the Ming Dynasty stayed at the pagoda, personally writing the inscription "Junji Shen Gong" (峻极神功). Wu Zong, the Zhengde Emperor, visited Yingxian, dined and enjoyed the scenery at the pagoda, personally writing "Tianxia Qi Guan" (天下奇观) and donating money to have the eunuch Zhou Shan repair it. Since then, during the Wanli reign of Ming and Kangxi reign of Qing, it was repaired again, remaining resplendent to this day, truly a rare treasure of China.

…

Originally published in "Northwest Sui Luo Ji"

Reprinted in "Republic of China Shanxi Reader - Field Notes"

Title added by the editor

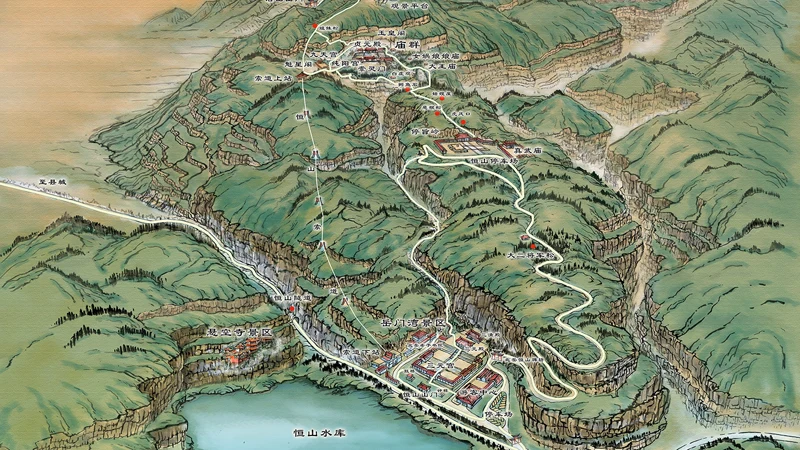

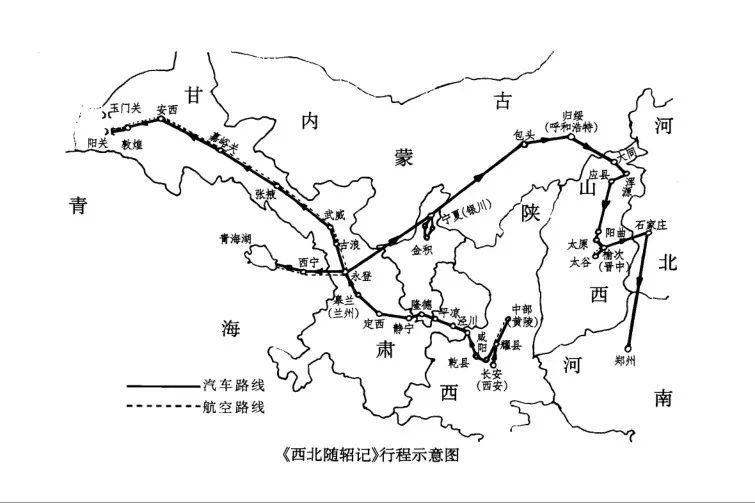

Itinerary map of "Northwest Sui Luo Ji"

Proofreading: Xue Fang

Editor: Xing Xuelin

Author's Introduction

Gao Liangzuo (1907~1968), courtesy name Mengbi, was from Songjiang, Shanghai, and served as Shao Yuanchong's secretary. In his youth, he attended Jiangsu Provincial Third Middle School, and later entered Shanghai Zhongshan University, where the president was Shao Yuanchong, who had previously served as Sun Yat-sen's confidential secretary. After graduating from Zhongshan University, he followed Shao Yuanchong to dedicate himself to the National Revolution. Before the Anti-Japanese War, he successively held positions such as Section Chief of the Political Department's Editing Section of the Whampoa Military Academy, editor of "Jian Guo Weekly" and "Jian Guo Monthly," and Director of the Editing Office of the Central Party History Compilation Committee of the Kuomintang. After the victory of the Anti-Japanese War, he served as Deputy Director of the Civil Administration Office of the Taiwan Provincial Governor's Office, concurrently serving as Executive Member of the Committee for the Repatriation of Japanese Nationals, Director of the Taiwan Provincial Cooperative Enterprise Management Committee, Advisory Committee Member of the Zhejiang Provincial Government, and Director of the News Office. He later went to Taiwan.

His major works include: "A Biography of Mr. Sun Yat-sen," "Notes from a Journey to Northwest China," "The Chinese Eastern Railway and the Far Eastern Railway Problem," "Wang Jingwei, the Traitor," "A History of the Chinese Revolution," and current affairs commentaries from "Jian Guo Weekly," totaling over 700,000 characters.

"Notes from a Journey to Northwest China" consists of ten chapters: "National Cemetery," "Journey to Longdong," "Lan Zhou Miscellany," "Journey to Qinghai," "Journey to Hexi," "Journey Beyond the Pass," "Return from Beyond the Pass," "Journey to Northern China," "Journey to Hedong," and "Record of the Return Journey." It provides detailed records of the history, geography, passes, scenery, social culture, customs, and education of Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi provinces, serving as important material for understanding the modern history and culture of Northwest China.

Keywords:

Hengshan

Related News