Fu Zengxiang's 1936 Travelogue of Mount Taihang during the Republic of China

Publish Time:

2025-03-18 11:51

Source:

In April 1936, Fu Zengxiang (courtesy name Cangyuan), a former Hanlin scholar and former Minister of Education, accepted the invitation of General Fu Yisheng, the chairman of Suiyuan Province, to serve as the chief editor of the "Suiyuan General Record." Accompanied by his eldest son Fu Zhongmo, nephew Fu Yumo, and fellow painter Li Yuling, he went to Guihuacheng (the old city of Hohhot), the capital of Suiyuan Province, to discuss the compilation of the record with colleagues from the Suiyuan Provincial General Record Office. Before leaving from Beiping for Suiyuan, Fu Cangyuan earnestly instructed his friends Zhou Yang'an, Xing Mianzhi, and Xu Senyu to join him for a tour of the scenic spots in Yunzhong and Hengshan Mountain on his return journey through Datong.

Editor's Note

In April 1936, Fu Zengxiang (courtesy name Cangyuan), a former Hanlin scholar and former Minister of Education, accepted the invitation of General Fu Yisheng, the chairman of Suiyuan Province, to serve as the chief editor of the "Suiyuan General History." Accompanied by his eldest son, Fu Zhongmo, his nephew, Fu Yummo, and fellow painter Li Yuling, he went to Guihuacheng (the old city of Hohhot), the capital of Suiyuan Province, to discuss the compilation of the history with colleagues from the Suiyuan Provincial History Compilation Office. Before departing from Beiping for Suiyuan, Fu Cangyuan earnestly instructed his friends Zhou Yang'an, Xing Mianzhi, and Xu Senyu to meet him in Datong on his return journey for a trip to the scenic spots of Yunzhong and Hengshan Mountain.

In mid-April, Fu intended to return to Beijing from Suiyuan and therefore invited his friends Zhou Yang'an, Xing Mianzhi, and Xu Senyu to meet him in Datong from Beiping. Due to prior engagements, Xu Senyu was unable to keep the appointment. Zhou Yang'an (Zhou Zhaoxiang, courtesy name Yang'an, a former Qing Dynasty Juren, a renowned modern epigrapher and painter) then took his rubbing craftsman Zhang Hei and Xing Mianzhi (Xing Duan, courtesy name Mianzhi, alias Zheren, a former Hanlin scholar and prominent figure in the Republic of China) to Datong via the Ping-Sui Railway, planning to travel together to Hengshan Mountain in Hunyuan. From April 22nd to 30th, Fu's group traveled from Datong to Hunyuan, spending a total of seven days on the round trip. The mode of transportation from Datong to Hunyuan was a palanquin carried by mules, while from Hunyuan City to Hengshan Mountain, they used the official sedan chair of Li Zhaolin, the magistrate of Hunyuan County. During this trip to Mount Heng, Fu received warm hospitality from Li Zhaolin and other Hunyuan officials, and was guided by Luo Wenju, the county school inspector (an official in charge of education, equivalent to the director of education). After returning to Beiping, Fu wrote "A Trip to Mount Heng" to record the journey.

Fu's "A Trip to Mount Heng" was first published in the 1937 issue of "Yilin Monthly: Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (No. 9). In 1995, when "Cangyuan's Travel Notes" was published, "A Trip to Mount Heng" was included in "Volume 3." It is worth mentioning that the version of "A Trip to Mount Heng" in "Cangyuan's Travel Notes" has several omissions compared to the version in the "Special Issue on Mountain Travel." This journal uses the version published in the 1937 "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" as a basis to present the original text. This is hereby explained.

Travelogues of modern figures visiting Hunyuan and Hengshan Mountain have always been a focus of this journal. This article is now published for the enjoyment of our readers.

Companion Piece to the Travelogue

Han Zhongcheng | Zhou Yang'an's Trip to Mount Heng

Fu Zengxiang (1872-1950), courtesy name Yuan Shu, alias Cangyuan, was a native of Jiang'an, Sichuan, and a renowned modern Chinese bibliophile. He was a Jinshi in the Guangxu Wuxu examination, selected as a Shujishi in the Hanlin Academy, and appointed as a compiler in the Hanlin Academy. Later, he served as the director of education in Zhili. After the establishment of the Republic of China, he held the important post of Minister of Education in the Beiyang government, resigning and retiring during the May Fourth Movement.

A Trip to Mount Heng

Cangyuan | Text

April 22-30, 1936

Fu Zengxiang of Jiang'an

April 22nd, Bingzi year

In the early summer of Yihai year, I, along with Mr. Xing Zheren (courtesy name Mianzhi) and Mr. Xu Senyu, ascended Mount Heng, spending the night on Mount Zhu Rong. We then planned a trip to Mount Heng the following year. In late spring of Bingzi year, I stayed in Guihuacheng for a month, responding to the invitation of my relative Yisheng to work at the governor's office. On my return journey, I passed through Yunzhong. Yunzhong is only a hundred or so li from Hunyuan, so I sent a letter to Mianzhi and Mr. Zhou Yang'an, setting a date to meet. I arrived in Datong on April 22nd, and Mr. Xing and Mr. Zhou had already arrived from Beijing, and I was hosted at the guesthouse.

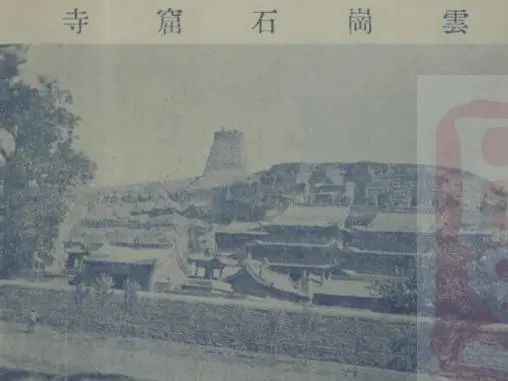

Yungang Grottoes

Yungang Great Buddha

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

23rd

In the morning, Yang'an and Yuling, together with Zhong and Yu, went to visit Yungang.

In the afternoon, Mianzhi and I went sightseeing in the city, first visiting Huayan Temple. The main hall, with nine bays, is magnificent and resplendent, a remaining structure from the Liao and Jin dynasties. The statues inside the hall are majestic, and the murals on the four walls depict Buddha images with exquisite colors, something rarely seen in my life. The location of the hall is very open, and from the steps, one can see the whole city. I heard that during the siege a few years ago, shells flew everywhere, and a hole was pierced in the ridge of the hall, but fortunately, the Buddha statues remained intact. The "Liao History" records that in the eighth year of Qingning, stone and bronze statues of emperors were enshrined in the temple. One bronze statue was of an emperor in imperial robes, but it is now lost. The plaque on the hall is inscribed by the Ming monk Huichuan. A side plaque inscribed by Ma Lin reads "Controlling the Gentleman," the characters are particularly powerful. In front of the hall is a Dharani pillar from the second year of Liao Taikang. The person who erected the pillar was Si Wenxian of Benshan Putong. The pagoda stands on Yangliupo in the west of the city; this pillar is not from the temple. Inside the hall are two steles from the Ming Dynasty, one from the government and one from the monk Jue Tong, which describe the construction history in detail and are valuable for research.

Upper Huayan Temple

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

Arriving at the Lower Huayan Temple, the main hall has five bays, and the statues are also grand. The upper structure is a magnificent building, and below is a lotus pond, with brilliant gold and colors, bright as new. Surrounding the hall are scripture libraries, called "Heavenly Palace Pavilions." The eaves are carved and decorated, connected by a flying bridge, with exquisite craftsmanship. The temple formerly housed Liao-dynasty engraved Buddhist scriptures, but they have been lost. The plaque on the hall reads "The Collection of the Buddha's Teachings," the calligraphy is simple and ancient, possibly an old plaque from the Liao or Jin dynasties, which has been repaired later, so the style remains. On the beams of the hall are two lines of inscriptions, from Yang Youxuan, the Jiedushi of Datong Army, who was also the governor of Yunzhou, built in the seventh month of the seventh year of Zhongxi, a total of more than ninety characters. There are two steles inside the hall. The left one is the record of the reconstruction of the "Collection of the Buddha's Teachings" in the second year of Jin Dading, written by Duan Ziqing of Yunzhong, and inscribed by the monk Fahui. The right one is the epitaph of the monk Furi Yuanming in the tenth year of Zhiyuan, written by Ruyi Laoren Xiangmai, and inscribed by the abbot Wuyuan. The east courtyard is the Haihui Hall. There is a record of the reconstruction during the Wanli reign, written by Shi Yuanzhong, but the calligraphy is by Tingkui, a member of the Lu Prefecture royal family, imitating the style of Chu He'nan, which is particularly elegant. I asked the rubbing craftsman to make a rubbing of it. We detoured to see the Nine Dragon Wall, with colorful glazed tiles, the scales and claws flying, its style similar to those in the Forbidden City and Beihai in Beijing, but more ancient and beautiful. The wall faces a square pond, the water of which has dried up. Next to it is a stele from the Qianlong era, written by the prefect Mu Te'en, which mentions that in a previous year of drought, a yellow dragon appeared in the pond, and rain immediately fell, which is also a strange story.

Locals say there is a Southern Temple, located in the shade of the South Gate city walls. My interest not yet waning, I drove on further. Upon entering, I learned it was the Shanhuasi Temple. The temple buildings were quite dilapidated, but the mountain gate was particularly grand, and the guardian deities were especially majestic and imposing. The main hall contained five Buddha statues, sculpted during the Ming Dynasty. The celestial beings on either side were sculpted during the Liao and Jin Dynasties; their expressions are vivid and lifelike, clearly the work of a master craftsman. Wall paintings remain on two walls and in the southeast corner; their brushwork is even more ancient and refined than that of the Huayan Temple. According to Zhu Shao Zhang's inscription on the main hall of the Puen Temple, "For the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, the Eight Heavenly Dragons and Devas surround them with clasped hands, all selected from renowned artisans. For the five hundred Arhats, the attendants and offerings each have their own instruments, all sculpted by skilled craftsmen." One can imagine the meticulous craftsmanship and the auspicious, radiant images that once illuminated the heavens. Although much has been reduced to ashes, the magnificent scale and design are still imaginable. I hear that a girls' school was once established in the temple, and most of the statues were destroyed. These few remaining statues, with their imposing forms, are a testament to what remains. The resident monk, Miaodao, a native of Sichuan, grieved over the destruction of the ancient site and tirelessly appealed to the capital. Officials took pity and issued an order to protect it; otherwise, even these remnants would have long since been reduced to ruins. However, the rafters and beams in the hall are gradually tilting, and urgent measures should be taken to preserve it.

Shanhuasi Temple

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

The temple possesses two Jin Dynasty steles. One is the "Record of the Reconstruction of the Main Hall of the Great Puen Temple in Xidu," written by Zhu Bian of Jiangdong in the second year of Huangtong, with the inscription written by Ding Wei and the calligraphy by Kong Gu. Zhu Bian, whose literary name was Shao Zhang, was sent to Jin during the early years of Jianyan and detained for seventeen years. He remained steadfast and unyielding, and because he stayed in the temple for a long time, he wrote this inscription. The inscription mentions his fourteen years of interaction with the temple community as if it were one day, thus fulfilling his request. The currently circulating "Qu Wei Old News" records the Qingliang Mountain in Daizhou and the Baiti Mountain Temple in Hunyuan, mostly what he heard and saw during his time in Yunzhong. As a work of a Song Dynasty official, it circulated in a foreign country (the Jin Dynasty) and remains complete and undamaged to this day, a true treasure. The other is the "Inscription on the Stele Commemorating the Completion of the Buddha's Enlightenment at the Great Puen Temple," written in the first year of Mingchang, recording the text of Wang Bo. The calligrapher's name is worn away, but Yang'an identified it as written by Wanyan Zhao. The calligraphy is solemn and imitates Pingyuan style, also valuable. Next to the hall are the two pavilions of Puxian and Wenshu, also remaining structures from the Jin Dynasty. Only the Puxian pavilion remains, but it is also in danger of collapse.

24th

Dawn, observing precepts. Two carriages were prepared, each carrying a large log, with ropes tied underneath for sitting and lying down, and mats on top for protection from rain and wind. This is the mode of transportation on the land routes of Shanxi. The use of logs in the Dayu Mountain area is reminiscent of this ancient method, isn't it? Three light carts and two guards accompanied us.

Leaving the South Gate, we turned southeast. Five li to Sha Ling, six li to Twelve Villages, three li to Xiao Nantou, seven li to Ai Zhuang, two li to Ta'er Village, eight li to Shangquan. We stopped to rest. Ten li to Zhoujiabao, five li to Nuo Zhenying, five li to Lirenzao, eight li to cross the Yuhe River, two li to Jiji Zhuang for the night. The countryside was impoverished, the houses dilapidated like stables, the water muddy like pulp, chickens and pigs scarce, and vegetables rare. The rice and flour were mixed with sand and stones; eating it was truly like grinding one's teeth. The hardships of the people of North Shanxi are truly imaginable.

25th

Early departure. Ten li to Wengchengkou, passing Matou Mountain. South of Datong is a plain, but here high ridges stretch across the clouds, extending for more than ten li. The carriage passed through the mountains. Along the cliffs and streams, houses were connected, forming villages. The road avoided water and climbed hills, often passing over the roofs of houses. Looking down, one saw green trees and flowing springs, as if looking into a deep well. Sitting precariously in the carriage, one felt a chilling fear of falling. This was also a unique aspect of the journey.

Ten li to Songshuwang, five li to Nigou, the mountain journey ended. Five li to Beiyulin, eight li to Jiangjiagou, ten li to Tuqiao Fort, two li to Hunyuan County. County Magistrate Li Xi Xuan and Zhao Lin greeted us on the left side of the road.

Once settled in the guesthouse, county officials and school students came to pay their respects. After a long time of socializing and a short rest with tea, we went out together.

Hunyuan Kuixing Tower

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

After investigation, it should be the county's drum tower or bell tower.

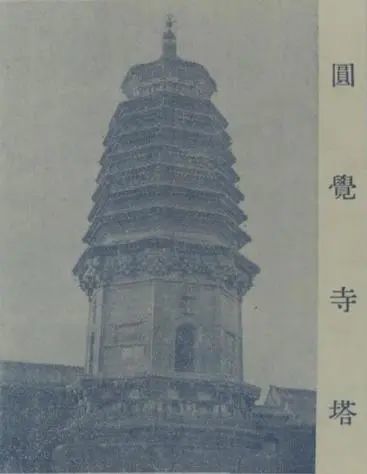

Entering the West Gate, we arrived at the Yuanjue Temple. The temple was built in the third year of Jin Zhenglong and rebuilt in the early years of Ming Chenghua. A nine-story brick pagoda stands at the entrance, dilapidated like an old monk, standing tall in the clouds. Two Ming Dynasty stone carvings are embedded in the pagoda's waist. The statues in the hall have been completely destroyed. I heard that in the past, troops were stationed in the temple and wantonly destroyed it, making it already unbearable. Later, when Feng Jun's army came from the west, Fang Zhenwu occupied the city, and the imperial army besieged it for eight months, resulting in complete destruction (Han's note: Fang Zhenwu did not break into the city, nor did the imperial army besiege it for eight months. This is a mistake by the author due to hearsay). Only a few Qing Dynasty stones remain in the courtyard, a cause for much sighing.

Yuanjue Temple Pagoda

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

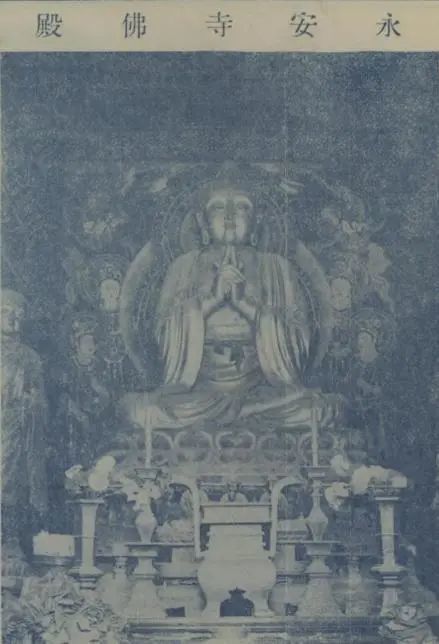

Turning northeast, we arrived at Yong'an Temple, commonly known as the Great Temple. Its layout is grand, its construction magnificent, and the colors of glazed tiles and gold shine brightly in the sky, even more vibrant than the old imperial palaces in the capital. The front hall housed the garrison troops; it had been modernized and there was nothing to see. The middle hall was relatively intact. After opening the door, we saw tall statues with exquisite and dignified features, and elaborate carvings.

Yong'an Temple Buddha Hall

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

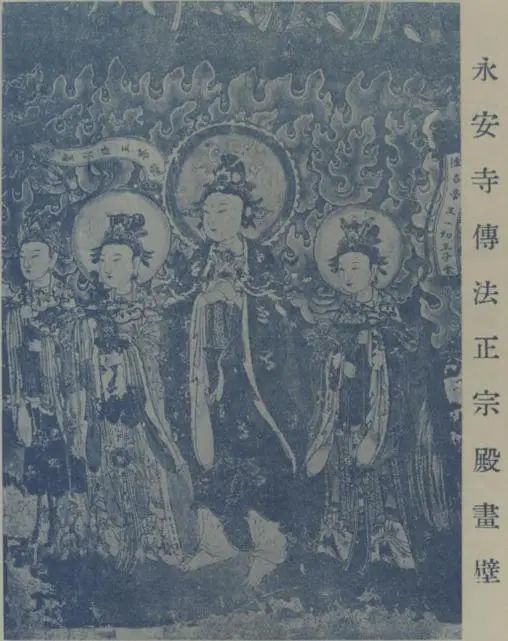

The four walls are painted with images of various deities and the rituals of men and women participating in water and land ceremonies. Their serene expressions and strange Buddhist images are as if flowing from the tongue, and their compassion emanates from their brows, making those who gaze upon them feel awe and reverence, as if they were at the Dragon Flower Assembly in a world of radiant treasures. Its design is extremely unique, and its colors are particularly rich. Compared to the works of the Huayan Temple in Datong, its ancient charm is even more outstanding, and it could not have been accomplished without the master craftsmen of the Jin and Yuan Dynasties. Zhonglang, a connoisseur of art, also happily admired it. Unexpectedly, in this ruined city and temple, we saw these treasures. He planned to use the new magnesium light method to photograph them and send them to fellow enthusiasts.

Wall Paintings in the Dharma Transmission Hall of Yong'an Temple

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

The hall's sign reads "Hall of Dharma Transmission," written by Xue'an Puguang of the Yuan Dynasty. Its style is strong and solid, and although it has been repaired many times over the generations, its form remains intact. Yang'an made a copy. Two steles at the foot of the steps are suspected to be from the Yuan Dynasty, but the characters are worn away and illegible. One pagoda is very ancient, but its age is also worn away. This temple has also been damaged by war, and bullet marks are still fresh on the walls. How many relics of our ancestors have been destroyed by such people? Alas, it is lamentable!

In the evening, Magistrate Xia Xuan came. We discussed the itinerary for Mount Tai and matters related to transportation and security, and he sent the official chef to the mountain to prepare food and drink. The thorough preparations were deeply touching.

26th

Good morning. Mr. Li Lingjun came and presented me with a copy of "Travel Notes of Hengshan Mountain" written by Zhen, a resident of the county, whose account is quite detailed and allows one to trace the journey with a map. He also gave me a volume of "Records of Ancient Objects," which records the discovery of bronze ritual vessels in Li Jiacun village in our county the year before last.

We set off at the beginning of Chen time, with Xiaoxuan and the school inspector, Mr. Luo Wenju, accompanying us as guides. There were no simple carriages in the city, so we used an official sedan chair. With its green mud coating, red mudguards, tin roof, gauze windows, and layers of ornaments all around, and two boys following on horseback, it looked just like the style of a high official's procession thirty years ago. Sitting in the chair, I couldn't help but laugh.

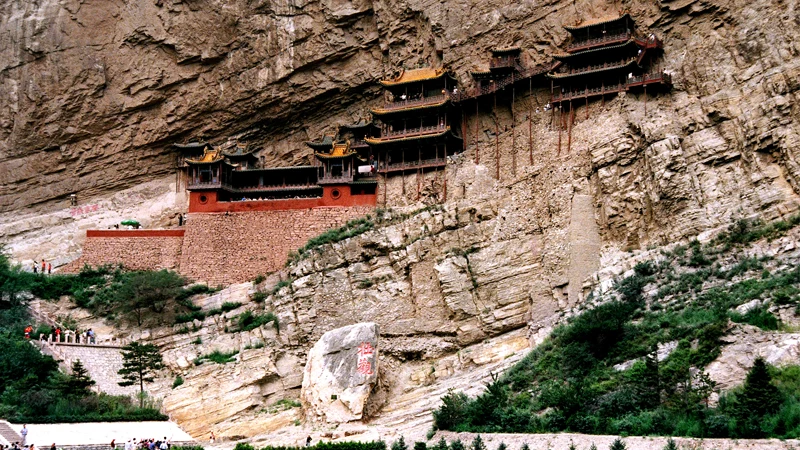

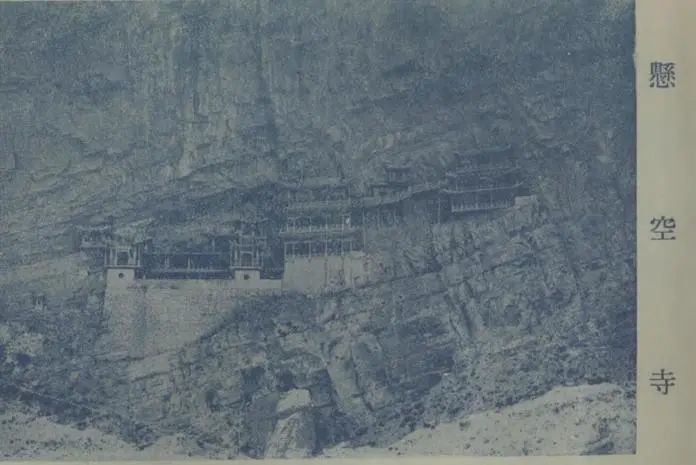

Leaving the south gate, we passed through fertile fields where straw hats were as numerous as clouds, a stark contrast to the vast expanse of yellow sand north of the county. At Qi Li Tangjiazhuang, we were already near the foot of the mountain. Along the way, channels were built with stacked stones, and cascading streams flowed into the paddy fields, resembling the beautiful countryside of the south. Entering Jinlongkou, Cui Ping Mountain was on the right, and a branch of Hengshan Mountain on the left; the two mountains stood side by side, their peaks piercing the sky. Water flowed through the gorge, with white waves surging—these are the Heng and Pi rivers. The "Shan Hai Jing" says: "Gao's Mountain, the Pi River flows from it." The county gazetteer states that Cui Ping Mountain is another name for Gao's Mountain. After entering the gorge for about a mile, high peaks encroached upon the clouds, and the two cliffs seemed to meet. People and horses crossed the stream by stepping on the stones along the ravine, like traveling through the three gorges of Kuizhou and Wuxian in Sichuan. Turning slightly westward, we suddenly saw mist and fog gathering, the deep valley shrouded in darkness. On the right, a towering cliff stood tall, its walls without steps, yet exquisite palaces and halls were scattered and suspended above, looking up, they seemed like pavilions in the air or divine mountains in the sea, making people feel refreshed and invigorated. This is the Hanging Temple outside the northern gate of Mount Heng. The gazetteer records that the temple was built during the Southern Song Dynasty, but this cannot be verified. However, Li's annotation on the Pi River states: "In the gorge, there is the Zhihuan Jinglu, Feilu Ling Mountain, Danpan Hongliang, Changjin Fanlan, winding below, flowing northeast into the Pi River." The essence of imitating mountains and rivers is right here. The construction of the temple in this gorge has a long history. Looking up at the sacred pass, my spirits soared, and I quickly climbed the more than one hundred stone steps to the temple gate. The middle building has two floors, and the main hall has five bays. Further in, the east upper building has three floors, the top being the Chongyang Palace, with a sign that reads "Fayu Jiushi," written by Zhang Chongde, the prefect during the Qianlong era (Han's note: should be Shunzhi). The west upper building has two floors, with a sign that reads "Zhanxi Yunge," written by Bai Zhong, a eunuch during the Ming Wanli era. Passing through a stone cave, we crossed a flying bridge about ten meters long. Beyond the bridge is a five-story high pavilion, the Taiyang Palace. There are signs that read "Qingxiao Dubu," written by the Taoist Sun Xun, and "Juebi Cenglou," written by Xu Shen of Wumen, both prominently displayed in the temple. The halls are filled with a mix of Buddhist and Taoist deities, including niches of the Buddha and Maitreya, and statues of immortals riding oxen and carrying swords. The decoration and carvings largely retain the style of the Jin and Yuan dynasties. There are two large Buddha statues carved from the rock, majestic and beautiful, with a particularly ancient style. The construction method involves cutting into the rock to create a foundation about one meter wide, with nothing beneath it. They then carved caves into the mountain, inserting large beams horizontally to support the sides, and long pillars to support the bottom. These are interconnected horizontally and vertically, forming a stable structure. Thus, the building is constructed in mid-air, with beams extending over dangerous cliffs, and low eaves flying like clouds, creating a breathtaking and ethereal sight that seems to float in the sky. I climbed, lingered, and gazed from the railing, imagining myself sailing on a vast ocean, with waves rising and falling, precariously floating. Occasionally, I heard human voices falling into the ravine, and the sound of bells and chimes floating in the air, like cranes flying on the Mount Gao Ridge, with a sense of ethereal ascension. Then, the sound of wind and springs echoed below the green forest, and the cries of monkeys echoed above the white clouds, making me feel as if I were in a fairyland, my emotions soaring, and my senses overwhelmed. I carefully examined the temple walls, finding many inscriptions from the Ming Dynasty, with only the couplets by Zheng and Luo being relatively neat. I added my name beside them to commemorate my visit.

Hanging Temple

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

Inside the temple, I found four steles with inscriptions from the Jin and Yuan dynasties. One was inscribed on the day before the Double Ninth Festival in the sixteenth year of the Dading era, with a seven-character quatrain and a preface, signed by the donors Wang Gongdao and Ma Xin. The poem and prose are crude and of little value, but according to the preface, we know that the abbot at that time was the monk Shan Ci from Shifoyuan Temple in Xuanning County, Yunzhong Prefecture, who was seventy years old and had lived there for eight years; another one dates back to the fifteenth day of the fourth month of the eighth year of the Dading era, and includes the names of Wu Dacheng, Yin Quan, Zhang Sitong, Zhao Daji, and Liu Jinchang; another is a fragment of the inscription on the memorial tablet of Chengying Gong, written by Zhang Shouyu, the magistrate of Ninghua Prefecture, and inscribed by Wang Mou. The text contains the year 4 of the Mingchang era, so it is also a Jin inscription; the last one lists the names of twenty-five donors, including Zhao Shun, who may have donated money for the construction of the pagoda during the Jin or Yuan dynasties. These are the oldest stone inscriptions in the temple and should be included in the local records.

I heard that there are two clerical script characters "Cui Ping" carved on the cliff face at the gorge entrance, but I did not have time to look for them. There are many carvings on the stone walls outside the temple, but the cliffs are high and covered with moss, making it difficult to see them clearly from a distance. The two characters "Magnificent View" on the left of the temple are said to be written by Li Bai, but this cannot be verified. There is a seal script inscription of "Xuankongyan" (Mysterious Void Cliff), about one meter tall, ancient and beautiful. After careful examination, I found that it was signed by "Yanling Xuankongzi Wengang," who is suspected to be a Ming Dynasty person, but is not recorded in the mountain gazetteer. Yang'an brought a skilled calligrapher with him to copy these inscriptions. Only the three characters "Xuankongyan" are carved high on the cliff face, requiring scaffolding to copy. More than a month after returning, Yang'an offered a substantial reward to obtain a copy, which was eventually sent to me. This shows the difficulty of studying ancient relics and Yang'an's courage and dedication, which is beyond the reach of ordinary people.

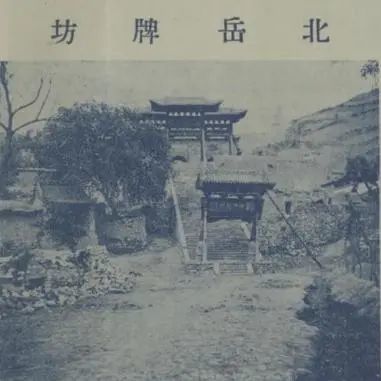

Northern Peak Archway

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

The locals said that there used to be a Baima Temple opposite the cliff, with a strange structure similar to this temple, but it has long been dilapidated. Looking from afar, one can still vaguely see the path. After a long chat, it was already past noon, so we left the temple and headed south. Along the cliffs by the water, many square holes were carved into the stone, which are the remains of old wooden bridges. There is a large inscription on the cliff face that reads "Yun Ge Hong Qiao" (Cloud Pavilion Rainbow Bridge), written by the educational supervisor Ai Gang. Next to it is the character "Qing," below which the characters are illegible. The county gazetteer records that Wu Kuan wrote "Qing Qi" (Pure Qi). In the gorge, the two rivers flow rapidly, and in the hot summer, they swell, making it impossible for carriages and horses to pass. The construction of bridges and rafts to help people cross is something that local officials should diligently attend to. From Jinlongkou Mulongwan to Ciyao Kou, the gorge stretches for seven or eight li, with steep cliffs and dangerous natural formations. At the point where the two cliffs meet, there are still traces of ancient carving. According to historical records, in the first year of the Tianxing era of Emperor Daowu, 10,000 soldiers were mobilized to excavate Hengling and build a straight road from Wangdu Tiemenguan to Dai, a total of 500 li. It is suspected that the construction started from here.

Leaving the gorge, we arrive at Ciyao Kou. Historical records mention a stone carving of "wind gourd and silk fans" by Zhang Junxiang, but I was unable to find it. From here, the mountain gradually opens up, with Li Mu's Shrine and the Dharma Cave on the right cliff, both of which I did not have time to visit. Further on, we reach a small village called Xia Po, with the Yue Temple gate clearly in sight. There are dozens of stone steps leading up to a stone archway. Two iron mythical creatures, with inscriptions on their backs indicating that they were created by Zhou Huai, a government official during the Wanli Yuan Dynasty, sit in front. Beyond this are three stone doorways with glazed tiles, looking bright and new. To the left of the gate is the Sanyuan Palace; after a short rest inside, I was disturbed by the chanting of a Taoist priest who was teaching a child. Leaving the palace, I followed the Buyun Road, which is the main road to Yue Temple, winding upwards. The scenery was bleak and desolate, like traveling through a chaotic mountain range. Five li further lies the Zhiling Ridge, with the Zhenwu Temple in front of the village, and three tall pines known as the "Dadafu Pines." After passing through a desolate valley village with earthen walls and earthen houses, where dozens of families made their living digging coal, the abandoned pits and old caves were as dense as beehives, with coal dust accumulated and rubble scattered everywhere. As Yue Temple is a nationally important shrine with solemn ceremonies and annual visits from envoys, it's deplorable to find such squalor nearby. The lack of proper governance is truly lamentable!

East Zhenwu Temple

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

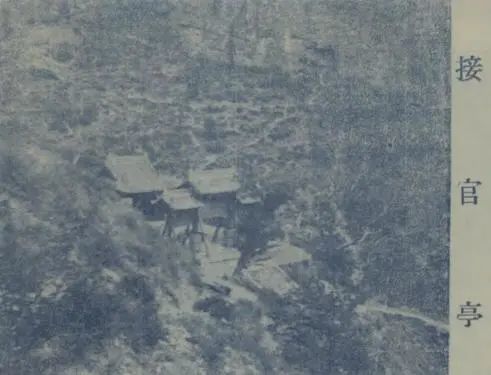

After this, ascending hundreds of steps, we reach the steep, high red cliffs of Daziliang, so named for the inscription of the two characters "Hengzong" carved into the stone wall. Looking north, the central peak rises majestically into the sky, with the grandeur of a dragon palace and a canopy of treasures. Turning northwest and climbing a high ridge, the wind is fierce and biting cold, giving the place its name, "Tiger Wind Mouth." The shape of the mountain protrudes, and the wind blows constantly, as fiercely as a tiger. Nearby is a stele inscribed by Dong Xishu, titled "Jie Shi." A short distance ahead is Guolaoling, with hoofprints on the stone, believed to be traces of immortals. Beyond the ridge, the trees become denser; looking north, we see the red walls and green tiles of buildings arranged intricately among the trees and hills, like a painting unfolding before our eyes. After half a li, we reach the official reception pavilion.

The Official Reception Pavilion

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

Descending and walking, the road winds nine times, leading to the Yue Temple. Entering the Chongling Gate, several steles stand on either side; only the inscription by Zhang Chongde is notable, although its ornate style lacks elegance and refinement. At the end of the stele, there is a quatrain by Feng Minchang with a fresher style. Inside the gate, on either side are the Qinglong and Baihu Halls, with a steep staircase with ninety-eight steps. Ancient cypresses line the path, their cold green casting a shadow. Above the steps is the South Heaven Gate; inside the gate is the main hall, the Xuanling Palace, where the Antian Xuansheng is worshipped. The abbot, Gao Yuanqing, invited me to stay in the right annex of the hall in a red-painted room.

Hengshan Mountain North Peak Xuanling Palace

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

My exhaustion eased, and my spirits lifted. Guided by the Taoist and Luo Jun, I went out. A plaque on the temple door reads "Zhenyuan Hall." Zhenyuan is a Yuan Dynasty title, so this plaque is likely an old relic. Stone steles stand before the hall, all Qing Dynasty imperial sacrificial texts; there are no carvings from the Yuan or Ming dynasties. The hall is tall and magnificent, a remarkable structure in the mountains, yet it pales in comparison to those in Song and Dai, let alone the temples in the West and South Peaks. The image of the Yue Emperor is imposing, yet the craftsmanship lacks antiquity, likely being made in recent times. However, four portraits of Daoist figures on the wall are powerfully drawn, but sadly lack inscriptions. To the left is a changing room, and to the right is a sutra library where many Ming dynasty sutras have been lost. Yuanqing showed me an imperial edict issued in the 27th year of the Wanli reign, granting sutras. The paper and ink are vibrant and exquisite. There was also a seal from the Yuan Shengdi of Hengshan Mountain. When the army entered the city during the Renxu year, the former magistrate took the seal, and local gentry took over county governance and used the seal for official documents; this is an unusual story of Yue Temple.

Hengshan Mountain North Peak Sleeping Palace

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

Descending the mountain past the Dawang Temple, crossing a stone bridge, and heading east along the foot of the cliffs, after about a li, we arrive at the old Yue Temple. Built since the Northern Wei Dynasty, it was repeatedly destroyed by war and fire until the Jin and Yuan dynasties. During the Hongzhi reign of the Ming Dynasty, the censor Liu Yu, seeing that the old temple was dilapidated, chose a site on the sunny side of the central peak and rebuilt the main hall, using the old temple as a sleeping palace. This location is surrounded by cliffs and has a hollow area inside, like a cave. The cliff faces the hall from a distance of about five zhang; the high cliffs are like outstretched wings. The left wing curves, forming a screen in front. The gap between it and the right wing is only about one zhang wide; in front of this gap is a gate. The gate overlooks a precipice; horizontal beams and posts support a bridge across the twenty zhang chasm. Historical records call it the floating bridge, but it is now paved with stone. The hall is built against the cliff; the cliffs overhang it like collapsing clouds. In front is a small platform. The space is too narrow for a staircase, but the structure is quite ingenious. Inside is a shrine dedicated to the Yue God; in the hall, there is a shrine to Kang Taiwei. The Huanyuan Cave is on the left side of the hall, dark and hard to see. Initially, there were no wonders, but during the Ming Dynasty, Huang Yingkun removed the stones blocking it and renamed it "Fu Huantian Qiao", adding an inscription to the stone. This was considered a good deed. Exiting the hall and going up to the right, beside a mountain shrine is a small cave called Feishiku. According to legend, a large rock fell from here to Quyang, leading to the origin of the worship. This stone is still in the Quyang Yue Temple. During the Hongzhi reign, Yan Zheng wrote about this event, but it is somewhat difficult to verify.

North Peak Floating Bridge Pavilion

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

In front of the hall is the Floating Bridge Pavilion, a square building, popularly known as the "Dressing Tower." Climbing the tower to look out, we see a plaque by Su Keji that reads "Layers of mountains and lush greenery." The cliff walls are covered with colorful carvings and inscriptions; the three characters "Yide Peak" are particularly imposing. On the cliffs on either side, there are many inscriptions, mostly written by envoys and visitors who came to worship and visit Yue Temple since the Ming dynasty. The beautiful mountains and peaks are adorned with engravings. The words of Wang Xianchen, and poems by Hu Zongxian and Qiao Yu, are particularly notable. A short stele on the left wall is inscribed with a seven-character quatrain entitled "Luquan," expressing profound grief; it was likely written by someone from the period between the Ming and Qing dynasties. I immediately ordered it to be copied for further study. Looking back, we see Baiyundong, halfway up the Zanyungang cliff; it is too dangerous to climb. Next to it are the four characters "Baiyun Lingxue," resembling a partially closed cave door; locals use the clouds emerging from it to predict rain. Going south from the old hall, one can take a path to Xiyang Ridge, where there's a hermitage, but the dangerous road prevented my visit. Looking up at the steep cliffs, a small cave is slightly visible, protected by a low wall, and there's someone living there. I asked Yuanqing, who said the cave was above the Yan Dao Shrine; it was previously abandoned, but last year, a man named Wang from East China went there to live in seclusion. He supported himself and his child by lowering food and water, living a secluded life in the mountains.

Hui Xian Fu

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

We rested briefly at the temple, then climbed again to the right of the cliff, visiting the imperial stele pavilion, the Meeting Immortals Mansion, and the Qinqi Terrace, among other historical sites. The Meeting Immortals Mansion is located on the cliff to the right of the temple. The area is spacious and offers a clear, expansive view. Tall maple trees, sparse ancient pines, and lush purple vines create an unparalleled, secluded beauty. Several rooms are nestled within the cliff face, housing statues of numerous immortals. To the east are the Wan Shou Pavilion and the Wenchang Pavilion; to the west, the Imperial Stele Pavilion, which bears the imperial inscription "Transformation Endures Through Time." To the north is the Gathering Immortals Cave, but it is dilapidated and we did not enter. Further west and north is the Qinqi Terrace. After climbing the rocks, we reached a flat area with a chessboard, used only by shepherds and woodcutters for their leisure. It lacked the refined atmosphere of scholars. We lingered, inquiring about the Xuan Yuan Valley, which lies further west in the ravine. It is overgrown and filled with rubble, and the stone gate is long gone. The north cliff is covered in inscriptions, many large and prominent. One inscription reads "The First School of Kunlun," written by Wu Dingyan, said to be a Liao dynasty person, though I did not have time to examine it closely. As dusk approached and the wind grew cold, we hurried back.

Passing the west gate, Yuan Qing showed me the Golden Rooster Stone. When struck, it produced a faint echo, but nothing else remarkable. Only an ancient pine tree behind it, its branches reaching out like a dragon's claws, was truly picturesque. It has long been called the "Four-Clawed Dragon" by the locals.

That night, I visited Luo Junwen, inquiring about the affairs of the county school. I learned that primary school teachers receive only seven taels of silver per month, while middle school teachers receive only ten. This poverty is truly lamentable. Do those in charge of education even consider this?

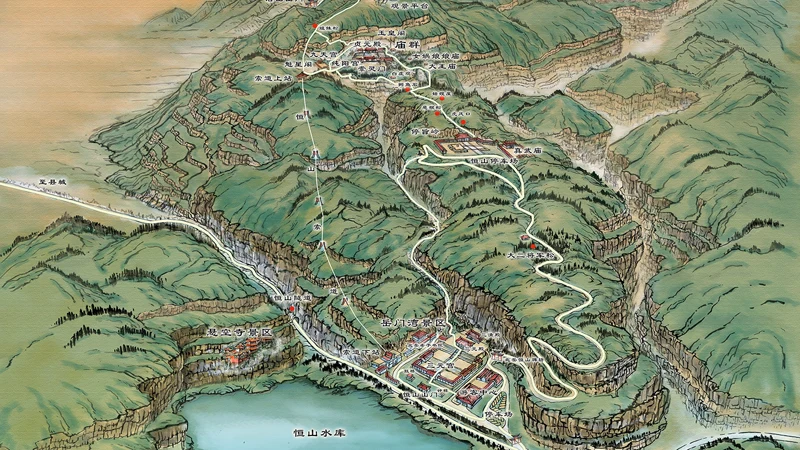

Hengshan Mountain Temples and Observatories

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

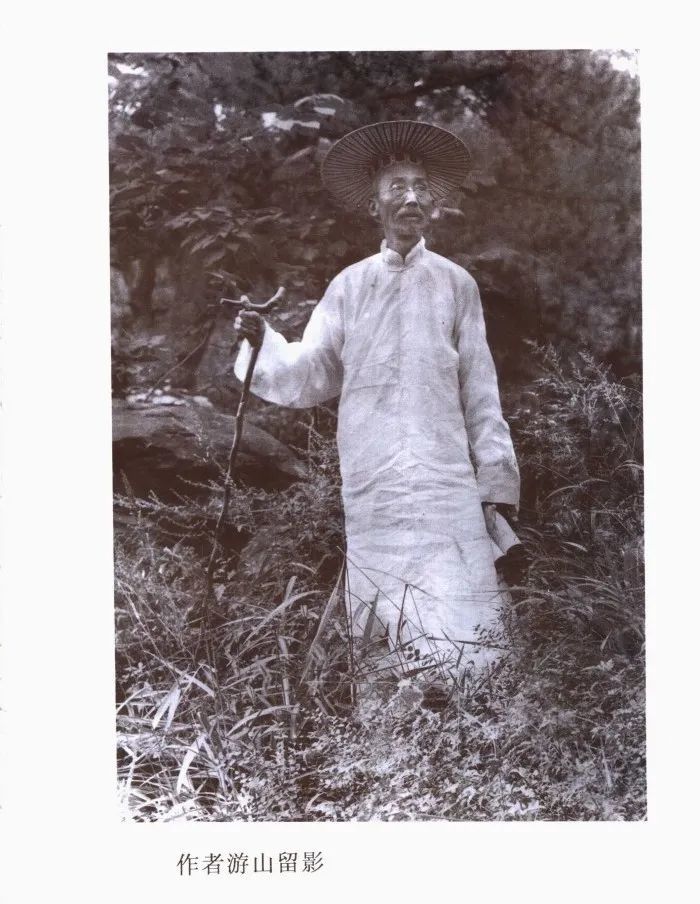

The 27th

I woke up early, and Yang'an had already left for a morning excursion. Zhao Chuanbi and Yin Chengzhi came to visit; both are military officers from Shanxi Province. They came to admire the mountain and we spoke briefly. They gave me two volumes of travelogues before departing. Yesterday, I searched the mountain for stones from before the Ming Dynasty, but found none. Yang'an returned and said he had seen an iron cloud board in the main hall with a Taiding year inscription, which he happily copied. The front inscription reads: "Long Life and Protection Heavenly Venerable, Taiding Year 1, March, made by Qi Yanju." The back reads: "The Abbot of the Longquan Observatory on Mount Yueshen, Hunyuan Prefecture, Datong Road, Master Hou Zhizhong, and the names of those who contributed to the observatory." I loved the secluded beauty of the Meeting Immortals Mansion, so I returned in the afternoon. I had Zhonglang paint a portrait of me under a pine tree and inscribe a five-character poem next to the imperial stele to commemorate my visit.

After dinner, I visited the Zhenyi Terrace to the left of the temple. I climbed a path along the stream, which was about 150 steps long. Thorns and brambles snagged my clothes, and sharp rocks hindered my progress. It took a long time to reach the top. There was a large rock about a meter high, with a flat top suitable for spreading a mat. I climbed to the top and looked out at the nearby mountains and distant waters, the white mist and blue haze, which broadened my mind. I inquired about the Zizhi Ravine, which is nearby. According to records, during the Jiajing era, the imperial court needed herbs and ordered the collection of northern Mount Tai's Xuanzhi fungus. The magistrate Song Ju was sent to the mountain and collected twelve specimens, which resembled cloud brocade. This became an annual practice, and Ju wrote "The Ganoderma lucidum Collection Record" to document the event. I entered the ravine, but the streams were dry, and the valley was overgrown, with no trace of the precious herbs. I wanted to climb to the peak to enjoy the pine wind of Hengding, but a woodcutter told me it was still two li away, so I turned back. I saw a solitary peak and climbed to its top, where there was a flat rock suitable for sitting or lying down. Zhonglang was still in the valley, so I called him up. I took a picture of myself on the peak, which truly captured the feeling of standing on a high peak.

I returned to the temple and said goodbye to Yuan Qing before leaving. I traveled west, visiting temples along the mountain, such as the Dragon King Temple, the Linggong Temple, the Guan Di Temple, the Wenchang Temple, and the Taiyi Temple, as well as the Dabei Pavilion, the Lingyun Pavilion, and the Doumu Pavilion. They were all small structures nestled among the green trees and red cliffs, only three or four rooms each, and rather dilapidated. I reached the Jiutian Palace, which is also the Bixia Palace, dedicated to the Golden Spirit Saint Mother and the Nine Heavens Profound Girl. The location is spacious and open, with sparse pines, giving it a certain charm. The courtyard is quiet and far from the hustle and bustle. To the left is the Dabei Pavilion, and next to it is the Lingyun Pavilion, with bright windows, ideal for viewing the distance. The Yuhuang Cave stands behind it, with exquisite pavilions, also a fine structure. The former Cui Xue and Wangxian Pavilions are only indicated by their remaining foundations in the bushes. A little further ahead is the Chunyang Palace, newly built and quite magnificent, with paintings of pines and plums in an old style. A Taoist priest invited me into the alchemy room for tea. Besides the Yue Temple, these two places are the most pleasant for visitors to rest.

Ancient Pine Tree at the Mountain God Temple

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

Nearby temples include the Bai Xu Guan, the Ziwei Pavilion, the Mountain God Temple, the Plague God Temple, and the Horse God Shrine. They are dilapidated and uninviting. I visited the Xuanwu Well, located to the left of the Bai Xu Guan, covered by a square pavilion labeled "Liyi Spring." The inscription on the spring pavilion was written during the Guangxu reign, and it is also called "Qianlong Spring." The local records say that "in a small area, there are two springs with different tastes." I drank from it, and it tasted sweet and clear. Another well nearby contained only dirty water. There are many steles around the spring, with poems by Liu Shiwei, Wu Yan, Zheng Luo, Xiong Mingcheng, and Gui Jingshun, all praising the spring. The discovery of a spring in the mountains is precious, but people always marvel at its miraculous nature, spreading its supernatural powers, which is quite amusing. After the visit, I got on my carriage in front of the town and arrived at the mountain gate, where Yang'an had been waiting for me at the Sanyuan Palace for a long time.

I crossed the stream to the west and saw the Luohan Cave in the cliff face. I followed the stream up a narrow path and entered. The cave was about three meters wide, dark and deep, and its bottom was unknown. Legend has it that during the Guangxu reign, a monk saw a strange ox-like creature at night, which was frightening, so they blocked the entrance with stones, leaving it abandoned for many years. Recently, a Taoist priest surnamed Zhang came here and raised funds to renovate it. Three rooms were built at the entrance, facing a large stream. Water marks on the rocks resembled silver, and in summer, the waterfall was spectacular. I left my name at the cave entrance. The Dama Cave is below, several meters wide and spacious enough to live in. There is a side room to the west, also bright and airy, but unfortunately, it is neglected. About a hundred steps down the west slope, there is a large rock shaped like a house, with the inscription "Tai Bai's Remains," written by Wang Xianchen, a Ming dynasty censor. Passing the Hanging Temple, I was delighted that my interest in sightseeing had not diminished, but I was also worried about missing the wonders, so I stopped the carriage and lingered for a long time.

I entered the city as dusk approached. Mr. Li, the magistrate, hosted a banquet at the guesthouse to welcome me, and we chatted casually. I learned that he had served in Shanxi Province for more than 40 years, and this is his second term in Hunyuan. He is over 60 years old. Recently, due to the implementation of new policies and numerous laws, the county government has established public welfare groups, resulting in a lot of miscellaneous matters, leaving him overwhelmed and considering retirement. In his spare time, he is also interested in literature and art, skilled in painting orchids. He has compiled a collection of Tang poems as titles for his paintings, and gave each of us a painting of orchids and a two-volume collection of Tang poems. He asked me to write an inscription, but I was too busy to do so, promising to write one and send it to him later.

The 28th

Early in the morning, Li Lingjun arrived. After a short stay, we set off. The magistrate and his officials and students saw us off at the outskirts of the town, and stayed to see us off for a long time. The two officials were copying murals of Buddhist images from Yong'an Temple, proceeding slowly. After noon, we passed Ni Gougou, and Li Ling had already sent people to the post station to prepare, but he insisted on refusing. When the two officials arrived, we set off at Shenke. Passing Matou Mountain, we stayed at Ji Jiazhuang for ten miles.

The 29th

At noon, we arrived at Xiaquan. We tested horses with Zheren Liuying, and each took a picture. We took a detour to visit Liuquan Bay, which is ten miles outside Datong City. There are tens of thousands of willows, with dense shade in four directions. There is a clear spring in the center, gushing out from the ground, overflowing into two pools, flowing into a long canal for irrigation. Beside it is a majestic high mound, with a dragon temple built on top, and small pavilions for viewing. Outside the temple, there are two pavilions on the left and right, with a stele inscribed by Governor Lu Kun. Inside the temple is a couplet written by villager Wu Hongen. Wu Gongzi Chunhai is from Tongliang. In the early years of Guangxu, he served as a Hanlin imperial censor in Shuoping, and this is what he inscribed when he was the prefect of Yunzhong. According to records, the spring source has two pools, "Purunquan" and "Aikequan," forming a bay. With green plants and willows, clear water and trees, you can take a short boat ride for swimming. In the Northern Wei Dynasty, buildings on both banks were connected, called "Liugang." In the Zhengtong period of the Ming Dynasty, Liugang Temple was built, and in the Daoguang period of the Qing Dynasty, Magistrate Li Zhongfu repaired it, which is believed to be the present temple site. The border is desolate and cold. Suddenly encountering this clear stream and jade, the dust was washed away. I composed two quatrains in the car to commemorate it.

In the evening, we entered the city and returned to Yanjing by car the next morning. The tour of Mount Hengshan was completed in seven days.

Mount Hengshan Temple in Quyang

Illustrations from "Special Issue on Mountain Travel" (Volume 9)

According to historical records, Hengshan Mountain is the town mountain of Bingzhou, as seen in the "Zhou Li." Its name "North Mount" first appeared in "Erya." During the Han Dynasty, it was changed to "Changshan" to avoid the emperor's taboo. It is called "Xuan Yue" and "Yin Yue" according to "Shui Jing Zhu." It is called "Hongshan" according to "Shangshu Dachuang." It is called "Qingfengtuo" according to Buddhist texts. It is called "Zongyuandongtian Jinchenfudi" according to Taoist texts. Other names such as "Damaoshan" or "Shenjianshan" are according to "Kuodi Zhi." The mountain is ten miles high and 130 miles in circumference. It is connected to Yuhua Peak in the north, Baishan in the southeast, and Qiangfengling in the southwest. Its veins extend from Yinshan to the areas between Shuoping, Zuoyun, and Youyu, passing Hongtaoshan to the Guancan Mountain watershed. It turns east to Pandao Liang, Gouzhushan, Yanguan Pass, and Malankou, and rises south of Hunyuan as Hengshan Mountain. Its main peak is Tianfengling, where the old Yue Temple is located.

Since the Han Dynasty, it has been worshipped in Quyang. During the Ming Dynasty, Ma Wensheng and Hu Laigong repeatedly requested to change the worship to Hunyuan, but Ni Yue and Shen Li opposed it, so it did not happen. In the early Qing Dynasty, in the 17th year of Shunzhi's reign, it followed the request of Nianbensheng, and the ceremony in Hunyuan was finally established. However, Gu Tinglin and Yan Qianqiu both argued against it, leading to disputes and heated debates in both places. To be fair, Hengshan Mountain is blocked by the desert on the outside and connected to the passes on the inside. It stands as a barrier for China and protects the capital. Its majestic presence is unmatched by other mountains. However, according to the maps and records I consulted, the area of Hengshan Mountain that spreads across northern Wei is extremely vast. "Guan Zi" describes the mountain: it faces Dai in the north, looks down at Zhao in the south, and connects to the Hehai area in the east. Speaking of the veins of the mountain, from north to east to south, it rises and falls through Zijin and Daomalu to reach Quyang, then reaches Feihugu in the east, Sangqianyin in the north, and reaches the Xiongguan dangerous passes east of Gouzhu, all being the winding and turning lands of Hengyue, which is the main peak of Gao's. It is also the ancestor of Damaoshan. Quyang is its foot, Fuping its ridge, and Hunyuan its peak. In this 500-mile area, which part is not blessed by the spirit of the mountain? Why be so insistent on one place to argue about right and wrong? Is this not a narrow view? As for the ceremonies, all the temples of Tai, Hua, Song, and Heng mountains are located on the sunny side of the mountain, or even tens of miles away. In ancient times, people looked up to mountains and rivers, and also used them to meet feudal lords and examine customs. This was their original intention. Now, abandoning the bright and flat land of Quyang and the centuries-old ceremonies, and rushing to a dangerous, remote, and isolated area, building a temple on the top of a deep valley and a cave, isn't this a mistake of the ritual officials?

Although its name is among the Five Great Mountains, its appearance is far inferior. The mountain body is low and barren, and the atmosphere is withered. Compared to the spiritual wonders of Tai and Hua Mountains and the abundance of Hengshan Mountain, the difference is vast. Moreover, its cultural relics are desolate, and its literature is quiet. Unlike Song and Dai Mountains, where ancient inscriptions are abundant for people to appreciate. In addition, it is located in a remote border area, and the roads are difficult. Therefore, looking through the records of those who visited Hengshan in the past, except for Qiao Yu, Xu Xiake, and Yang Shucheng, there are very few famous articles. In recent times, Li Yunlin went to Niejiazi Ridge, crossed Zijinguangguan, climbed to the top of Damaoshan, to seek the so-called "true form of Xuan Yue." Although the intention is curious and unique, it also shows that the scenery of this mountain is ordinary and cannot attract attention, which has been the case for a long time. Therefore, I record my journey here, referring to historical records and writings, detailing them in this article. Even if the old sites are long gone, I still record their names for future generations to explore. The tediousness of it is beyond my concern. As for the relics in the mountain, such as the deep and beautiful Fuchiao Pavilion, the tall and strange Huixian Mansion, which were once famous areas and landmarks for sightseeing, if we can clear away the weeds and rocks, the beautiful buildings will be bright and the view will be wide. Those who live here will have a poetic and romantic mood, and those who live here can look for the secret of cultivating immortality. I hope that future outstanding people will design and build the place, so that this blessed land can have a unique view. When I return in the future, I hope to enjoy more beautiful scenes here.

Originally published in "Yilin Monthly: Special Issue on Mountains," Volume 9

Travel Notes of Mount Hengshan (1937)

Special Issue on Mountains and Travel Notes of Mount Hengshan

Background Information

Yilin Monthly: Special Issue on Mountains was founded in Beiping in 1929 and ceased publication in 1937. It was an irregular art publication with a total of 9 volumes, published by the Yilin Monthly Publishing House. The parent publication of the Special Issue on Mountains, Yilin Monthly, was founded in January 1930 and was a monthly publication. It inherited Yilin Weekly. The first issue of Yilin Monthly was also issues 73-75 of Yilin Weekly. The time and reason for its cessation of publication are unknown. Yilin Weekly was founded in Beiping in 1928 by the China Painting Study Society and edited and published by the China Painting Study Society. It was a weekly publication and ceased publication in December 1929. It was inherited by Yilin Monthly.

Yilin Weekly (and Yilin Monthly) was sponsored by the Chinese Painting Research Society and should have been the society's journal. The reason for using "Yilin" in the title was to reflect the intention of gathering talents widely and not being limited to the biases of the society. The articles published aimed to explore the future of Chinese painting, showcase various paintings such as Southern School, Northern School, meticulous brushwork, and freehand brushwork, introduce the lives and works of famous painters and calligraphers from various dynasties, and explain painting and calligraphy techniques. The articles published were mostly about calligraphy and painting, poetry, and ci, along with a large number of paintings, seal carvings, etc. The Chinese Painting Research Society was founded in 1920, with its office located at No. 24, Fafa Hutong, Xuannei Dajie, Beijing. It was initiated and established by leading figures in the Beijing painting circle, such as Jin Cheng (founding president), Zhou Zhaoxiang, and Chen Shizeng, representing the mainstream of the national painting circle at that time. Zhou Yang'an (Zhou Zhaoxiang, courtesy name Yang'an, director of the Palace Museum Antiquities Exhibition Office from 1926 to 1928), the leader of the Jingjin painting school, served as the president of the Chinese Painting Research Society from 1926. Yilin Weekly, Yilin Monthly, and Youshan Special Issue were all founded under the leadership of Zhou Yang'an.

Zhou Yang'an loved traveling and his footprints covered the whole country. He had many friends, learned scholars, and celebrities, and often invited them to travel together, writing articles, poems, and taking photos to record their journeys, forming a small group of mountain travelers centered around Zhou Yang'an and Fu Cangyuan. In 1929, six gentlemen, namely Fu Yuan Shu (Fu Zengxiang, courtesy name Yuan Shu) from Jiang'an, Zhou Yang'an from Shaoxing, Xu Senyu (Xu Hongbao, courtesy name Senyu, from Wuxing, Zhejiang, a famous antique appraiser) from Wuxing, Jiang Yiyun (Jiang Yong, courtesy name Yiyun, from Changting, Fujian, a modern legal scholar) from Changting, Zhou Lizhi (Zhou Xueyuan, courtesy name Lizhi, from Zhide, Anhui, a poet and educator) from Jianshi, and Ling Zhizhi (Ling Wenyuan, courtesy name Zhizhi, from Taixian, Jiangsu, a master of flower-and-bird painting and economist) from Taixian, gathered together and decided to compile their travelogues and poems written during their visits to Baihua Mountain, Lianhua Mountain, and other mountains into the first volume of a special issue of Yilin Monthly, hoping to guide and inspire the younger generation to pursue noble entertainment and cultivate strong physiques. Thus, the Yilin Monthly: Youshan Special Issue was published.

However, the members of the mountain-traveling group were not fixed for each trip, but were temporarily invited and organized, so some peripheral members joined. For example, in 1936, there were 7 participants in the trip to Mount Taihang, namely Fu Cangyuan, Fu Zhongmo (Cangyuan's eldest son), Fu Yummo (Cangyuan's fourth nephew), Li Yuling (Cangyuan's fellow painter), Xing Mianzhi (a Hanlin scholar of the Qing Dynasty), Zhou Yang'an, and Zhang Hei (a rubbings expert). Fu Cangyuan, Zhou Yang'an, and Xing Mianzhi were core members of the mountain-traveling group, while the other four were temporary peripheral members. Regarding this trip, Fu Cangyuan wrote "Travelogue of Mount Taihang" and Zhou Yang'an wrote "Travelogue in the Clouds," which were compiled and published in the 9th volume of Yilin Monthly: Youshan Special Issue in 1937. This volume also included Fu Cangyuan's "Travelogue of Jinci Temple" and "Travelogue of Wutai Mountain," and Zhou Yang'an's "Diary of Wutai Mountain Trip." This was the last issue of Yilin Monthly. Shortly after, the "July 7 Incident" broke out, the country was in ruins, the mountain-traveling group disbanded, and Yilin Monthly ceased publication permanently.

Proofreading: Xue Fang

Editor: Xing Xuelin

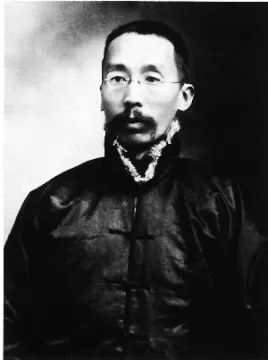

Fu Zengxiang (1872-1950), courtesy name Runyuan and Yuanshu, other names included Shuangjianlou Zhu ren, Qingquan Yisou, Changchun Shi Zhu ren, and later Cangyuan, Cangyuan Jushi, and Cangyuan Laoren, was from Jiang'an, Sichuan. In his youth, he studied at Lianchi Academy in Baoding, under the tutelage of Wu Rulin, a master of ancient prose from Tongcheng. In 1898, he passed the imperial examination and became a Hanlin scholar. Later, he served as the director of education in Zhili, and was commissioned to establish girls' normal schools in Tianjin and Beijing, becoming a founder of public girls' schools in China. Enter the Republic of China, he entered Yuan Shikai's government. In 1914, he became a member of the Provisional Parliament of the Beijing government, and in 1915, he served as the director of the Department of Supervision. In December 1917, he was appointed Minister of Education, gaining considerable reputation. During the May Fourth Movement in 1919, Cai Yuanpei, president of Peking University, and Fu Zengxiang, Minister of Education, resigned successively for protecting students and resisting the orders of the Beiyang government. In 1927, Fu became the director of the library of the Palace Museum, leaving the post in 1929. After the Lugouqiao Incident in 1937, Fu stayed in Beiping, engaged in the collection and collation of ancient books. From 1938 onwards, he served as vice president and president of the East Asia Cultural Agreement Association controlled by the Japanese puppet government, which has been criticized by later generations. On the eve of the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Zhou Enlai specially sent Chen Yi with a handwritten letter to visit him, but Fu Zengxiang had already passed away before Chen Yi arrived.

▲Portrait of Cangyuan, painted by Xu Beihong

Fu Zengxiang devoted his life to the study of ancient books, collecting a total of more than 200,000 volumes, including more than 100 Song editions (3,400 volumes), 60 Jin and Yuan editions (more than 3,500 volumes). Among his collection, more than 16,000 volumes were personally collated. He wrote "Shuangjianlou Shanben Shumu" (4 volumes), "Cangyuan Xiaoshu Lu" (4 volumes), "Cangyuan Qunshu Tijiji" (20 volumes), "Cangyuan Qunshu Jingyan Lu" (19 volumes), and "Cangyuan Dingbu Kaoting Zhijian Zhuanben Shumu" (23 volumes), totaling about 3 million characters. Except for "Xiaoshu Lu," all of them have been published. Hundreds of precious Song and Yuan editions, famous calligraphers' and scholars' annotated books, and more than 16,000 personally collated books from his collection have been donated to the country and are now kept in the Beijing Library; 30,000 Ming and Qing ordinary fine books and dozens of self-carved book editions were bequeathed to his hometown, Sichuan Province, and are now kept in libraries across the region. Fu was a famous scholar of editions, catalogs, collation, and a great collector of books in modern times. His collection of fine books was the largest among private collections of his time, making him a leading figure of his generation.

Fu Zengxiang left immortal academic achievements in the field of ancient literature, but he was by no means a person who merely spent his time reading thousands of books in his study. Beyond his research and collation of ancient books, he had a refined love for mountain travel, long admiring the high achievements of Li Daoyuan and Xu Xiake, and expressing his feelings for the beauty of mountains and rivers through writing. After middle age, he travelled extensively for years, his travels over 40 years covering the Five Great Mountains and famous scenic spots in Southeast, North China, Inner Mongolia, and Northwest China. Over the years, he wrote more than 30 travelogues, including those about the Five Great Mountains, Huangshan, Jiuhua, Tiantai, Yandang, Tianmu, Jingshan, Lushan, Laoshan, Lingyan, Wutai, and places in the suburbs of Beijing, Hebei, Inner Mongolia, and Guanzhong. Before setting out on his journeys to various places, he would always extensively read historical records, gazetteers, books on mountains, temple records, writings by local celebrities, and ancient and modern travelogue poems and prose, thus gaining a basic understanding of the local customs and historical sites. During his travels, he vividly described his daily observations and investigations, meticulously listing and studying inscriptions on stone tablets and cliffs, cultural relics, and the inscriptions of famous scholars, incorporating them into his records, paying particular attention to items that were missing from historical records or new discoveries, in order to illuminate the profound historical and cultural origins of these scenic spots. There are 33 travelogues by Fu Zengxiang extant. Some chapters were published in the "Yilin Xunkang-Travel Section" in the 1930s, and in the early 1940s, 14 of them were printed in a small number of woodblock editions. In August 1995, Fu’s 33 travelogues, compiled by his grandson, Fu Xinian (an architectural historian and academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering), were published in sixteen volumes under the name "Zangyuan Travelogue," totaling 300,000 characters and published by the Printing Industry Press.

Keywords:

Hengshan

Related News

Tourists visiting Hengshan Mountain, in addition to appreciating the magnificent natural landscape of Hengshan Mountain, are more interested in learning about the profound cultural heritage of the Northern Mountain.

Republic of China hemp mat treasure | Guiyou (1933) Deng Hengyue Ji (with poems and texts)

In today's ancient city of Hunyuan, when discussing well-preserved ancient residences, one must mention the "Ma Family Courtyard." The original owner, Ma Xi Zhen, has also gained attention, as if the person is known because of their residence.