Hengshan Mountain's Fool | A Brief Talk About Su Baoheng: His Life and Legacy

Publish Time:

2025-09-17 10:14

Source:

A brief overview of Su Baoheng and his accomplishments

Text / Hengshan Mountain, Fool

Regarding Su Baoheng, I’ve always had this vague, elusive feeling—sometimes it seems as though I see him clearly, yet at other times, he appears shrouded in a hazy mist. On one hand, if we say he wasn’t from Hunyuan, why is it that many local chronicles of Hunyuan County still list him among the region’s distinguished scholars, even mentioning that his tomb lies beneath a hill seven li northwest of Hunyuan city? On the other hand, if we assume he was indeed from Hunyuan, why does the *History of the Jin Dynasty* place him instead as a native of Yunzhong Tiancheng—a region that corresponds to today’s Tianzhen County in Datong City? According to the *History of the Jin Dynasty*: "Su Baoheng, courtesy name Zongyin, was born in Yunzhong Tiancheng." After all, county gazetteers document the history of specific regions and counties, while the *History of the Jin Dynasty* covers the broader narrative of an entire nation. Yet determining which account holds greater authority or accuracy remains uncertain, as even national histories often draw heavily on materials compiled by individual authors. For instance, the *History of the Jin Dynasty* itself was essentially pieced together from two key works: Liu Qi’s *Guiqian Zhi* and Yuan Haowen’s *Renchen Zabian*.

Su Baoheng (Image from the internet)

I’m interested in a person named Su Baoheng—first, because Su Baoheng might have been from Hunyuan, and as someone who shares the same regional background, I naturally find him intriguing. Second, Su Baoheng served as the "Envoy to Celebrate the Spring Festival," sent annually by the Jin dynasty’s emperor to the Song court to mark the Lunar New Year; moreover, he also played a pivotal role as a negotiator in peace talks between Jin and Song. According to the *Song Shi: Benji, Volume 32*: "On the day Renzi, the Jin dispatched Su Baoheng and others to pay tribute for the upcoming Spring Festival." Similarly, the *Jin Shi: Benji, Volume 5* records: "In the eleventh month, on the day Xinyou, Su Baoheng, then Minister of the Ministry of Works, was appointed along with others as the envoy to celebrate the Song Dynasty's Spring Festival." When I was younger, I often listened to Liu Lanfang’s storytelling of *The Biography of Yue Fei*, which filled me with deep-seated hatred toward figures like Jin Wushu. But now, as I’ve grown older, I’ve come to view the conflict between the Jin and Song dynasties as a rivalry between two rival regimes within the same vast territory. Moreover, at that time, our hometown, Hunyuan County in Datong City, was still under Jin rule. Thus, while I still hold onto my reverence for Yue Fei’s unwavering loyalty to his country—and maintain a sense of national unity—I no longer harbor intense animosity toward the Jin dynasty. My mindset has become much more balanced. As a result, Su Baoheng, as a key figure bridging the Jin and Song courts, has naturally piqued my curiosity and drawn me to explore his role and significance further.

I. Su Baoheng, Who Devoted Himself Entirely to His Duty

According to historical records such as the "Jin Shi," Su Baoheng, courtesy name Zongyin, was born in 1113. His ancestral home was likely in Yunchengtiancheng. His father, Su Jing, was an imperial scholar of the Liao dynasty who later became the military governor of Xijing—essentially the chief administrative official of Datong. It is speculated that Su Baoheng, seeking to escape the turmoil of war, moved with his mother from Tianzhen County to Hunyuan County. During his youth, Su Baoheng studied at Cuiping Academy, located on Cuiping Mountain in Hunyuan County—a renowned institution at the time. Notably, Liu Hui, Jin China's first-ever top scholar in literary composition and rhetoric, was also a student there around the same period. By then, Su Baoheng had probably already settled permanently in Hunyuan. In April 1122, the Jin army launched an attack on Xijing (modern-day Datong, Shanxi), forcing Liao Emperor Yelü Yanxi—the last ruler of the Liao dynasty—to flee. Seeing that resistance was futile and aiming to safeguard the lives of Datong’s residents, Su Jing, the military governor of Datong, ultimately surrendered the city to the Jin forces. As Su Jing lay gravely ill and near death, he entrusted the Jin commander-in-chief, Zong Han, to take care of his young son. After Su Jing passed away, Zong Han honorably fulfilled this promise by recommending Su Baoheng to the imperial court—though the boy was only 10 years old at the time. Following the Jin conquest of Datong, they retained the city as Xijing while reorganizing the region from Xijing Dao into Xijing Lu.

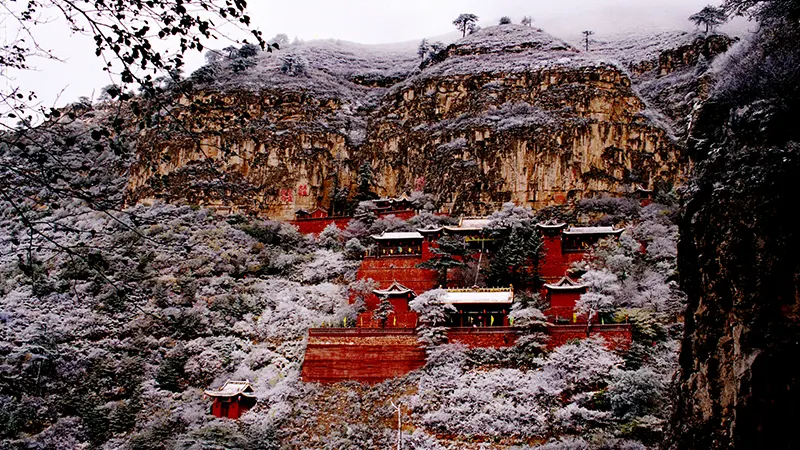

Former Site of Cuiping Academy

In 1128 AD (the sixth year of the Tianhui era), Su Baoheng, who had been diligently studying all along, followed his mother's wish and traveled to Xijing to take the imperial examination. At just 16 years old, he ultimately impressed the court with a remarkable second-place ranking in the palace examination, earning him high praise from the imperial authorities. From that moment on, Su Baoheng embarked on a distinguished official career, serving with unwavering dedication and leaving an enduring legacy that would be remembered for generations. Initially, the court bestowed upon him the title of "jinshi," appointing him to fill a vacant position. Crown Prince's Horse Groom , serving as a mediator for the provincial military judge. He was later appointed to the staff of Zuo Jianjun Salihai, where he served as a military advisor and participated in the construction projects of the Jin Dynasty's central capital and imperial tombs. During the Song-Jin conflicts, he commanded the naval forces of the Zhe-Dong region as the Grand Commander of the Water Fleet, overseeing shipbuilding operations and leading his fleet across the sea in combat. Unfortunately, his forces were defeated by the Song navy, resulting in the Grand Commander's tragic death at sea. In the second year of the Dading era, he was dispatched to Shandong to provide disaster relief, ordering grain from government granaries to aid those in need. For those without clothing, he distributed currency and textiles; if official grain supplies fell short, he arranged for additional purchases to meet the demand. Meanwhile, individuals lacking spouses had their names submitted for official consideration. Later, he was also sent to Henan, Shandong, and Shaanxi provinces to comfort and support soldiers stationed in agricultural colonies, bestowing commendations upon those who demonstrated exceptional military achievements. As a key negotiator in the Song-Jin peace talks, he played a pivotal role in brokering the eventual reconciliation between the two dynasties. Following this, his career advanced steadily until Senior Minister and Right Vice Minister The high position.

In 1167 AD, Su Baoheng, who was plagued by illness, repeatedly petitioned the emperor to retire and return home—but each time, the emperor warmly persuaded him to stay. That winter, Su Baoheng finally passed away at the age of fifty-five. At the moment of his death, the Jin dynasty’s emperor was out hunting in the suburbs; upon receiving the devastating news, he immediately returned to the capital and ordered the Ministry of Rites to organize a solemn memorial ceremony. Throughout his life, whether confronted with immense power or vast state wealth, Su Baoheng remained utterly dedicated, impeccably honest, and tirelessly devoted to his duties—working himself to the very brink of exhaustion before passing away. His remarkable talent, combined with his unwavering integrity and lofty moral character as an official, earned him the deep respect and trust of the Jin emperor. Indeed, such a life was something that even Han Chinese officials like Su Baoheng could rightly take pride in. As lauded in the *Jin Shi* (History of the Jin Dynasty): "Su Baoheng, Zhai Yonggu, Wei Ziping, Meng Hao, and Liang Su—all were outstanding statesmen of their time."

II. Su Baoheng, Who Climbed the Ladder of Success

As the old saying goes: "A thousand-mile horse may be common, but a true master who recognizes its worth is rare." Su Baoheng's career path has been remarkably smooth—ever since he encountered his mentor, Zonghan, he has steadily risen through the ranks, soaring effortlessly to great heights. The sheer number of prestigious high-ranking positions he has held is truly astonishing.

According to the Ming Wanli edition of the "Hunyuan Prefecture Gazetteer," Su Baoheng was a *jinshi* of the Second Class, second-ranked candidate, having passed the imperial examination in the sixth year of Tianhui. Meanwhile, the "History of the Jin Dynasty" records that Su Baoheng was awarded the title of "Ci Jinshi Chushen," which specifically referred to those who, after successfully passing the palace examination, were bestowed this honor by the court as members of the Second Class. In other words, all individuals recognized as "Ci Jinshi Chushen" were indeed *jinshi*, but not every *jinshi* received this particular distinction. Those ranked first among the *jinshi* were titled "Ci Jinshi Jidi," while those in the third class were called "Ci Tong Jinshi Chushen." Thus, it is clear that Su Baoheng earned his scholarly status through a formal examination. A few years earlier, Liu Hui had become the top scholar—known as the "Zhuangyuan"—in the second year of Tianhui, earning him the title "Ci Jinshi Jidi." Interestingly, both men had been students at Cuiping Academy, highlighting the academy's reputation as one of the premier educational institutions during the Jin dynasty. Their presence there underscores Hunyuan County's status as a cultural and educational hub, reflecting the region's prominence in the nation's intellectual and academic landscape at the time. However, historical records also reveal that Su Baoheng was not well-versed in Confucian classics or historical texts. As noted in the "Chronicles" section of the "History of the Jin Dynasty" (Volume 19), Emperor Shizong remarked: "Although Right Vice Minister Su Baoheng, despite being Han Chinese, lacks proficiency in Confucian classics and history, Vice Minister Shi Ju excels in these areas yet remains silent. Given that the previous ceremonial officials were already stripped of their posts for similar lapses, shouldn’t even you feel alarmed? Submit detailed accounts of past dynastic rituals so I may review them and decide how to proceed." At the time, the Jin dynasty’s imperial *jinshi* examinations primarily tested candidates on their skills in composing literary essays and poetry—subjects that Cuiping Academy students focused heavily on. By contrast, classical Confucian texts and historical studies were largely overlooked in the curriculum. This explains why Liu Hui, who won the prestigious title of Zhuangyuan, did so specifically in the category of literary composition rather than in classical scholarship.

The Hunyuan Prefecture Gazetteer records (image from the internet)

After Su Baoheng passed the imperial examination and became a jinshi, he officially embarked on his official career, serving successively as太子洗马 and Military Judge of Jiezhou. Deputy Governor of Xingzhong • Deputy Prefect of Daxing, Commander-in-Chief of the Naval Forces in Zhejiang East Circuit, Senior Advisor and Minister of Public Works, Minister of Finance, Director of the Bureau of Rites, Minister of War, Minister of Justice Senior Vice Minister of State Affairs "Right Vice Minister" and other official titles. "Prince's Wash Horse" is a specific official position. Originally known as "Xianma," it was first established during the Qin and Han dynasties. The Han dynasty continued the Qin system by placing it within the Eastern Palace administrative structure. When the prince traveled, this official would lead the way ahead; in peacetime, the primary role was to assist the prince, guiding him in matters of governance and scholarship. During the Han period, the salary grade for this position was equivalent to 600 *shi*. By the Jin dynasty, its responsibilities had shifted to that of a court librarian. During the Sui dynasty, it was renamed the "Sijing Bureau Wash Horse." By the Qing dynasty, it had become a fifth-rank official position, which remained until the very end of the Qing era when the post was finally abolished. In the "History of the Jin Dynasty," "supplementing the Prince's Wash Horse" refers to assigning individuals who had earned the title of *jinshi* (successful candidates in the imperial examinations) to serve in this particular role. The "Jiezhou Military Judge" was a subordinate official serving in the military administration at the prefectural level during the Jin dynasty. Primarily, this position assisted the chief official in handling administrative and military affairs—such as managing military documents, planning and advising on military strategies, and overseeing routine tasks related to daily army operations. In the term "Tongzhi Xingzhong Yin," "Tongzhi" denotes an official title referring to a deputy or vice position, while "Xingzhong Yin" is the chief official of the Xingzhong Prefecture—a regional administrative division that existed during both the Liao and Jin dynasties. Thus, "Tongzhi Xingzhong Yin" specifically designates the deputy official who assists the Xingzhong Yin in managing all administrative matters of the Xingzhong Prefecture. Another official title is "Daxing Shao Yin." "Daxing" was a significant place name during the Jin dynasty; the Jin dynasty once established Daxing Prefecture there, which served as the administrative center of the capital city, Zhongdu. "Shao Yin" refers to the deputy official assisting the prefect himself in handling governmental affairs. Lastly, "Zhedong Dao Shuijun Dutongzhi" designates a high-ranking military commander responsible for leading the naval forces stationed in the Zhedong region. In the "History of the Jin Dynasty: Biography of Su Baoheng," Su Baoheng held this position, indicating that he oversaw all naval affairs in the Zhedong area. During military campaigns, he had the authority to deploy and direct these naval units effectively. Historical records show that, leveraging the power and responsibilities associated with his office, Su Baoheng led the navy directly from the sea toward Lin'an, the capital of the Southern Song dynasty. Jeongbong Dae-bu "It refers to the treatment accorded to officials at or above the third-rank civil administrative position. The positions of ‘Minister of Punishments,’ ‘Minister of Rites,’ ‘Minister of Revenue,’ ‘Minister of War,’ and ‘Minister of Public Works’ are relatively straightforward—they reflect how the Jin dynasty adopted the ‘Three Departments and Six Ministries’ system from the Northern Song, with each of the six ministries serving as a specialized executive body under the Ministry of Personnel. All six ministerial posts were held by officials of the third rank. Notably, Su Baoheng served as Minister of Personnel, though this particular role was not explicitly mentioned among his previous appointments. The title ‘Taichang Qing’ evolved from ‘Taichang.’ During the Southern Liang and Northern Qi dynasties, ‘Taichang’ officially became ‘Taichang Qing,’ taking on the primary responsibility of overseeing rituals related to ancestral worship, state sacrifices, imperial court assemblies, funerals, and other ceremonial functions. As an assistant to the emperor during these rites, the Taichang Qing also managed the emperor’s private temples, tombs, and mausoleums. In ritual ceremonies, this official guided the emperor in performing sacrifices; for smaller-scale rituals below the level of major state ceremonies, the Taichang Qing could even represent the emperor in offering sacrifices. The official held a rank of the third grade. ‘Canzhi Zhengshi,’ meanwhile, was one of the highest-ranking administrative officials during the Tang and Song dynasties, often grouped alongside titles like ‘Tongping Zhangshi,’ ‘Shumishi,’ and ‘Shumishi Fushi’ as part of the broader ‘Zai Zhi’ group. In the early Tang period, ‘Canzhi Zhengshi’ initially served as an additional title bestowed upon officials outside the three major departments, allowing them access to the Political Affairs Hall for deliberations. It wasn’t until the second year of Qian De in the reign of Emperor Taizu of the Song Dynasty (964) that ‘Canzhi Zhengshi’ was formally established as a deputy prime minister. By the sixth year of Kaibao (973), ‘Canzhi Zhengshi’ began regularly meeting with the prime minister at the Political Affairs Hall to discuss state affairs, gradually gaining powers and honors comparable to those of the prime minister himself. Although the position was briefly abolished during Emperor Shenzong’s administrative reforms in the Song Dynasty, it was later reinstated during the Southern Song era. Throughout the Liao, Jin, Yuan, and other dynasties, this official post was largely retained, though it eventually disappeared entirely after the ninth year of Hongwu in the Ming Dynasty. In the Jin dynasty, ‘Canzhi Zhengshi’ occupied a second-rank position. Lastly, ‘You Cheng,’ or Right Vice-Minister, referred to the Right Vice-Minister of the Ministry of Personnel. This position was first established during the reign of Emperor Cheng of the Han Dynasty, originally functioning as an assistant to the Minister of Personnel and the Chief Clerk. Over time, its status steadily rose, eventually reaching the second rank during the Jin dynasty—placing it on equal footing with ‘Canzhi Zhengshi’ as a key executive official and serving as the prime minister’s deputy. Thus, Su Baoheng’s highest-ever official appointment ultimately reached the prestigious second-rank position."

Su Baoheng was a filial son who lost his father at an early age, yet he and his mother relied on each other while never forgetting their late father’s aspirations. He was also an outstanding student, studying at the Hunyuan Cuiping Academy, where he diligently pursued his studies and eventually earned the prestigious second-class imperial examination ranking as a jinshi. As an official, Su Baoheng consistently governed with moral integrity, demonstrating unwavering dedication to his duties, passion for his work, and tireless efforts—always upholding the trust of both the court and the people. Moreover, as a beloved local figure, he remained deeply connected to his hometown, forever grateful for the nurturing influence of Hunyuan’s breathtaking landscapes. After his passing, he was even laid to rest by the banks of Shenxi Stream in Hunyuan, truly embodying his profound affection for his native land. In summary, Su Baoheng shares remarkable similarities with Li Yumei from the Qing Dynasty. The people of Hunyuan should take him as a role model, striving to become patriotic and virtuous individuals who honor both their hometown and their nation.

September 12, 2025, drafted at Yu Zhai

Keywords:

Related News