Republic of China: Guan Yingren | Hengyue Travelogue (1935)

Publish Time:

2025-10-17 19:10

Source:

On September 14, 1935 (the 17th day of the eighth lunar month), the renowned modern scholar Guan Yingren, accompanied by his friends Zhang Changyun, Zhang Shishi, Guo Liuyao, and others, set out from Beiping to explore Hunyuan. The journey lasted seven days, after which Mr. Guan penned "A Travelogue of Hengyue Mountain," which was subsequently published in the 10th volume, No. 1, of the *Travel Magazine* in 1936. Passionate about traveling and diligent in writing, he always pens articles to document his experiences wherever he goes. His most distinctive trait is that, during his travels, he never fails to acquire and consult local guidebooks, while also carefully studying other travelers' accounts. This allows him to follow the "map" of each destination with precision, ensuring a deeper understanding of both similarities and differences. As a result, his writings reflect a solid and meticulous scholarly foundation.

Travelogues by modern figures who journeyed through Hunyuan and Hengshan Mountain have always been a key focus of this publication. We are now pleased to share this article with our readers. Editor's Note

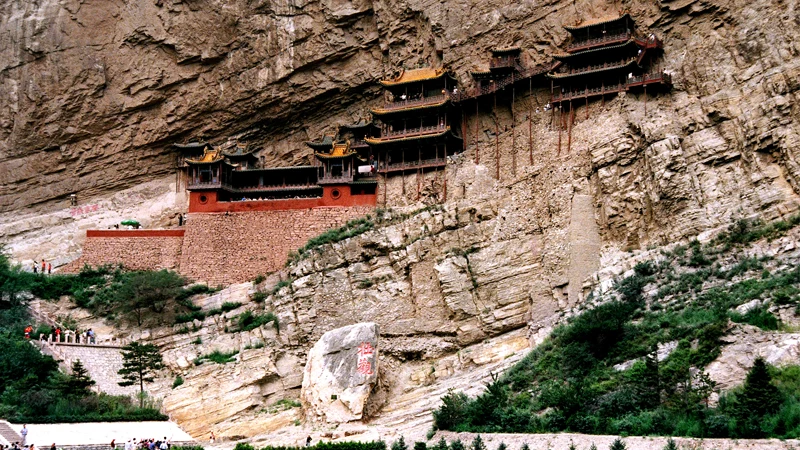

▲ Hengshan Mountain, the Cliffside Monastery Suspended in the Cui Ping Gorge

Illustrations in this article

Excerpted from "Travel Magazine," Volume 10, Issue 1, 1936

Guan Genglin (1880–1962), courtesy name Yingren, was born in Nanhai, Guangdong. He passed the imperial examination as a jinshi in the Guche Year of the Guangxu reign. A renowned poet, scholar, lyricist, industrialist, and educator in modern times, he was also a key figure in promoting China's railway development.

Hengyue Travelogue

Guan Yingren | Text

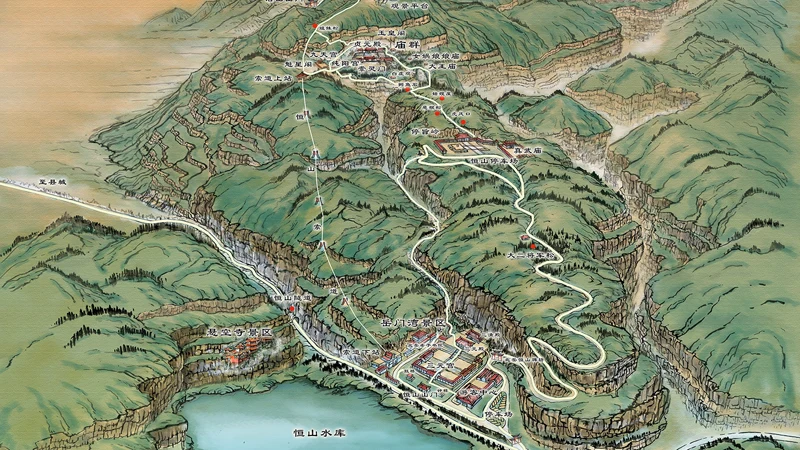

Hengshan is the most remote of the Five Great Mountains, with fewer, less prominent peaks that haven’t gained widespread recognition. Yet, some enthusiasts have even suggested challenging its status by awarding it to Wutai Mountain instead. At first, I myself was skeptical about this idea—but now I realize how unfounded it truly is. The mountain’s terrain is remarkably diverse: sometimes steep and sharply carved, other times broad and expansive; sometimes clustered into a single majestic form, and at other times branching off into two distinct ridges. Each configuration reveals the exquisite artistry of nature in seamlessly blending and shaping the landscape—yet despite these varied appearances, all forms ultimately converge to create one grand, unified whole. Hengshan Mountain itself originates from the Yinshan Range, extending southward from Yinshan through the regions of Suoping, Zuoyun, and Youyu, before crossing over Hongtao Mountain and reaching the watershed dividing line at Guancen Mountain. From there, it curves eastward, forming key landmarks such as Pandao Liang, Juzhu Mountain, and the Malan Pass of Yanmen Pass, before abruptly rising dramatically to the south of Hunyuan—a region that marks the main peak of Hengshan. Meanwhile, another branch of the range stretches eastward, flowing from Guangling into the territory of Zhili Province. Along this path lie iconic features like Feihu and Zijing Passes, all nestled beneath its towering presence. Meanwhile, the remaining foothills eventually fade away entirely toward the sea in a northeasterly direction. On the southern side, yet another branch extends southwestward, passing through Lingqiu and Fanzhi before entering Zhili Province once more. This segment gives rise to the Taihang and Wangwu Ranges, which then wind their way between Fuping and Quyang, culminating in the imposing Da Mao Mountain—the true backbone of Hengshan. From here, the mountain’s influence gradually diminishes, with its final remnants fading away in a southerly direction, ultimately meeting the river. Though Hengshan appears to split into three primary branches across its vast expanse, in reality, it remains a singular, cohesive mountain—united in both form and spirit.

Since the Ming dynasty, debates have been rife, with scholars like Ma Wensheng, Hu Laigong, Nian Bensheng, Yin Geng, and Xu Huapu advocating for Hunyuan as the true site of Mount Heng, while Ni Yue, Shen Li, and Wu Kuan insisted on Quyang. Each camp firmly held its own view. According to the "Geographical Records" in the "Book of Han," "Mount Hengshan is located in Shangquyang." This assertion has been consistently echoed by historical records throughout the ages. Similarly, the "Commentaries and Annotations on the Book of Documents and Zhou Rituals" notes: "Starting from the first year of the Shence reign of Emperor Xuan of the Han Dynasty, sacrifices to the Northern Yue, or Mount Changshan, were regularly conducted at Quyang." During the Tang and Song dynasties, these rituals were indeed performed in Dingzhou—this remains the foundational rationale behind the ongoing debate. Those who support the earlier claim argue that it was only during the Song dynasty that the idea emerged—that Mount Hengshan had disappeared beneath the Liao territory, prompting people in Quyang to continue offering sacrifices toward its supposed location. However, this narrative appears historically tenuous when examined closely against available evidence. As a result, throughout the entire Ming period—even though the imperial court officially recognized Mount Xuan in Hunyuan as the authentic Mount Heng—sacrificial rites continued to take place in Quyang. Despite numerous disputes among officials over the proper ritual practices, the only adjustment made was the renovation of the existing temple complex in Hunyuan. It wasn’t until the 17th year of the Shunzhi era in the Qing dynasty that the annual mountain sacrifice was finally relocated to Hunyuan. Yet, even then, the core issue remained focused solely on the location of the ritual site; no one ever questioned whether Mount Hengshan itself truly existed. In fact, the mountain’s status as the sacred "Northern Yue" remained unquestioned. Later, however, some individuals, driven by personal agendas, began challenging this consensus altogether, even going so far as to question the very existence of Mount Hengshan. As Shen Li pointed out: "The designation of Hunyuan as the 'Northern Yue' appears exclusively in local gazetteers and inscriptions. When examined through historical texts and commentaries, there is simply no reliable evidence to confirm this claim." Meanwhile, Wu Kuan remarked: "South of Hunyuan Prefecture lies a particularly towering mountain, widely believed by locals to be the original Mount Hengshan." And Xu Huapu added: "The name 'Hengshan Mountain' used in Quyang is merely a geographical reference—not an actual mountain. In fact, many seemingly coincidental occurrences across China involve similar misidentifications. The overlap between 'Hunyuan' and 'Hengshan' is just one such example, much like how the names 'Erhuo' occasionally coincide by chance." But isn’t this conclusion perhaps overly speculative?

I believe there is no doubt that Hengshan Mountain, as one of the Five Great Mountains, should be considered part of the same mountain complex as the other two. Examining various historical texts, we find in the *Guanzi*: "Hengshan Mountain faces Dai to the north, overlooks Zhao to the south, and stretches eastward between the He and Han rivers." Clearly, this description cannot apply to a single mountain alone—this serves as the first piece of evidence. In the first year of Tianxing during the Northern Wei dynasty under Emperor Daowu, the Hengling Pass was carved out to create a direct route. At the time, the Wei emperor was returning from Zhongshan to Pingcheng in the north, ordering 10,000 soldiers to construct this vital road, which connected Wangdu’s Tiedongguan Pass to Dai over a distance of more than 500 li. Today, Zhongshan corresponds to present-day Ding County in Hebei Province, located roughly 500 li southeast of Hunyuan. If we take the modern-day Ciyao口 area as the northernmost point, it aligns perfectly with this historical account. Thus, the two Hengshan Mountains can indeed be seen as a single entity, with the northern range clearly taking precedence—this provides our second piece of evidence. Furthermore, in the seventh year of Kaihuang during the Sui Dynasty, Quyang County was briefly renamed Hengyang; however, by the 15th year of Yuanhe in the Tang Dynasty, it reverted to its current name. Similarly, in the early Yuan period, Hunyuan County was initially called Hengyin, with “Shanyin” and “Shanyang” both referring explicitly to Hengshan. These three examples collectively reinforce the idea that the two Hengshan Mountains are part of a unified whole, with the northern range playing the dominant role. Pen-and-Paper Conversation 》It is recorded: "Hengshan Mountain in Hunyuan Prefecture lies over 300 li away from Damao Mountain in Fuping County, with peaks seamlessly connected. Indeed, Hengshan Mountain stretches for 3,000 li in circumference, and Hunyuan is situated 20 li south of it—yet it is, in fact, the same mountain as the one located 140 li northwest of Quyang." It is further noted: "Today, half of this mountain belongs to the Khitans, with Damao serving as the dividing ridge." These four points clearly establish the unity of the two regions. However, Gu Tinglin, in his poem on Mount Beiyue, specifically refers to Quyang. Yet, in his seminal work *Beiyue Bian*, he explicitly states: "Hengshan Mountain spans 300 li in length," adding, "I therefore first visited Quyang before ascending to Hunyuan." Here, "visiting" clearly refers to reaching the mountain's base, while "ascending" denotes climbing its lofty peak—thus providing five distinct pieces of evidence supporting their identity. This is precisely why Wei Yijie, in the preface to the *Quyang Zhi*, remarks: "Hunyuan stands atop the summit of Hengshan Mountain, while Damao represents its principal branch; originating from Hunyuan, the mountain range extends via Feihu all the way to Quyang." Similarly, the *Hunyuan Zhi* notes: "Hengshan Mountain lies 20 li south of the county seat, stretching continuously southward toward Damao Mountain in Fuping—a distance of over 300 li—and soaring southeastward until it reaches Quyang." None of these accounts ever suggest that the two mountains are separate entities. Even Wu Kuan, in the inscription for the restored North Yue Temple Stele, writes: "Wherever divine spirits reside, they come and go swiftly—when they arrive, it is Quyang; when they depart, it is Hunyuan." This sentiment echoes the very essence of their inseparable connection.

Since the North and South are essentially one mountain, it’s hardly surprising that the rituals were held either at the summit or on the sunny side of the mountain. During the Han dynasty, temples dedicated to the gods were built in Shangquanyang during the Shenjue, Yuanhe, and Taichang eras; and in the Tang dynasty, a temple was established in Shangquanyang during the Zhenguan period. Later, during the Yuanhe era of the Tang dynasty, the official rites were formally relocated to Quyang. In the Tang dynasty’s Zhenguan period and again under the Song dynasty’s Qiande and Zhenhe reigns, ceremonies were conducted in Dingzhou—each instance seemingly accidental. Wang Xiqi remarked: "When the Song lost control of Yunzhong, even light carriages couldn’t reach the area. Thus, they resorted to using flying stones as a pretext to cover up their own inadequacy." Meanwhile, Yin Geng observed: "The Tang dynasty lost northern Hebei, and shortly after, Shi Jinci ceded Yan and Yun to the Liao. Yet when the Song defended Zhengding, none of them managed to reach the foot of the mountain to present jade and silk offerings. Moreover, since these rituals were conveniently held in Quyang, no one ever bothered to correct this arrangement." Indeed, his assessment rings true. However, touring the mountain is entirely different from performing ritual ceremonies. While worshiping the mountain naturally takes place on its sunny side, exploring it invariably requires ascending to its lofty peak. Yet, despite never having climbed all the way to Hunyuan, one could still accurately say that they’ve never truly visited the Northern Peak itself.

▲ Hengshan Mountain Gate

Illustrations in this article

Excerpted from "Travel Magazine," Volume 10, Issue 1, 1936

I have traversed the Five Great Mountains—Taishan, Hengshan, and Huashan—but initially had no intention of visiting Hengshan. In the ninth month of the Year Yihai①, as I prepared for a trip to Wutai Mountain, I consulted with those who had already been there, who advised that it would take more than ten days. However, unable to commit to such an extended journey, I ultimately decided instead to head for Hengshan Mountain. On the evening of the second day after the Mid-Autumn Festival②, I departed from Beiping, accompanied by Zhang Changyun from Nanhai③, Zhang Shishi from Tongshan, and Guo Liuyao, also from Nanhai.

The next morning, we arrived in Datong. Stationmaster Gao Shengwen served as our guide to Yungang. Up and Down Huayan Temple Zhu Sheng and Guo Sheng returned ahead of the group. On the morning of the 19th, they departed separately in two mule-drawn carts. The journey from Datong to Hunyuan covered a distance of 120 li—roughly 60 kilometers—which a strong traveler could easily cover in a single day. However, due to some delays in packing their belongings, they arrived late, paying only four silver dollars for the cart fare. At 8 o'clock, they left the city and headed toward the South Gate, where they passed by the magnificent Jile Temple before turning eastward. By 3:45 a.m., they crossed the Shili River, also known as Wuzhou River. The area near the river was covered with fine sand, and a sudden gust of wind stung their eyes, making it hard to see clearly. At 2:12 p.m., after continuing southward to Miaor Village—referred to in Zhang Zhaosong's travel notes⑤ as "Sicun," though locals often mispronounce it as "Shiercun," suggesting it’s about twelve li from the city—this seemed unlikely. Along the way, lush melon fields were laden with ripe fruit, and both villagers, men, women, and children eagerly picked up slices of watermelon to enjoy—even the mules and horses couldn’t resist! It’s said locally that people traditionally savor watermelons during September and October. From mid-autumn onward, melons are carefully stored for consumption throughout the colder months, even enjoyed while gathered around a warm hearth until well into October. Yet, here in this region, we’ve grown accustomed to eating watermelon even after the autumn equinox without any discomfort—unlike back home, where consuming melon afterward often leads to stomachaches. By 2:12 p.m., they reached Neizhuang, located twenty li from Datong. There, they disembarked and walked several more miles on foot. At noon, after covering thirty li, they finally arrived at Shangquan, where they stopped briefly at Dongsheng Store. Unfortunately, the store offered nothing but steamed buns⑥, oil-fried noodle rolls⑦, and boiled eggs⑧—nothing else worth eating. At 1:15 p.m., they resumed their journey and reached Lilaocun by sunset, having traveled fifty li in total. Just three quarters of an hour later, they crossed the vast Sanggan River. Though the river was wide, with water lapping against the southern bank, local villagers brazenly waded across naked below the waist—a truly unsightly practice that should be banned immediately! After crossing the river, they continued southward until they reached Jijiazhuang, gradually drawing closer to Mount Guo⑨. Ahead lay the mountain pass, its rugged contours rising dramatically against the twilight sky. Mount Guo, also known as Hengshan, stretches northward from the Yunzhong Plateau, forming a dramatic range of peaks that resemble an imposing screen. As evening approached, they once again crossed the river, entering the narrow gorge of Guoshan Gorge—the very spot known as Wengchengkou, or "the Gateway of the Pot City." Despite the dense residential settlements lining the gorge walls, our cart driver initially suggested taking a break here. But we firmly refused, urging him instead to press on toward Nigou, where we would resume our trek. The canyon echoed fiercely with howling winds, and the chill grew sharper as night deepened. Towering cliffs flanked the path, occasionally punctuated by cascading waterfalls. The winding gorge stretched for about twenty li, offering no place to rest along the way. By the time darkness enveloped the landscape, the moonlight was already obscured by the towering peaks above. Yet, faint cries and shouts occasionally pierced the silence—revealing soldiers patrolling vigilantly along the roadside, which somehow brought us a sense of relief. Emerging from the gorge, they found themselves in a broad, open plain known as Songshuwan. Though still seven li away from Nigou, the first sliver of moonlight began to peek through the jagged rock formations, casting a serene glow upon the horizon. By 11:12 p.m., they finally reached Nigou and checked into Li’s old residence for the night.

Note:

① Yihai: The Yihai year of the Republic of China, which corresponds to 1935.

② Two days after the Mid-Autumn Festival: September 14, 1935, corresponding to the 17th day of the eighth lunar month.

③ Zhang Changyun from Nanhai: Zhang Yuchuan (1879–1953), courtesy name Changyun, was born in Nanhai, Guangdong. From April 15, 1918, to January 1920, he served as the president of Tsinghua School (the predecessor of Tsinghua University). Later, he held several positions, including Counselor at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs under the Beiyang Government, Advisor to the Pingjin Garrison Command, and Lecturer in the Preparatory Division of Peking University. During the Japanese occupation period, he served as Chairman of the Credentials Review Committee for the Wang Jingwei regime's North China Political Council. He passed away in 1953.

④The 19th: It should be the 16th; this is a mistake by the author.

⑤ Zhang Zhaosong’s Travelogue: Zhang Zhaosong (1867–1950), a native of Hepu, Guangxi, was a literary figure during the Republic of China era. After traveling to Hengshan Mountain in June 1919, he penned "Hengyue Youji," which was published in May 1921 in the journal *Xin Youji Huikan*. In the text, both "Zhang Ji" and "Zhang Youji" refer to this very travelogue.

⑥ Mantou: Steamed bun.

⑦ Oil-Fried Noodle Rolls: Youmian Rolls.

⑧ Chicken egg: Egg.

⑨ Mount Guo: Mount Guo should be located near Mazhuang and Baofengzhai Village in Hunyuan County, where the ancient county seat of Guo County lies at the foot of the mountain—this was the former administrative center predating the Later Tang period. However, this article incorrectly places Mount Guo near Jijiazhuang, indicating a mistake in the author’s memory regarding its actual location.

On the 17th, the weather was clear. Early in the morning, just after the first hour of the day, we climbed a small hill to watch the sun rise over the horizon. The courtyard faced directly toward Mount Hengshan, its dark, verdant slopes deeply shrouded in clouds and mist. At exactly 2:08 a.m., we set off. The mountain’s terrain is predominantly earthy; however, where water has carved through the soil, it often splits into deep ravines—what locals call "mud gullies." Looking down from our vantage point, we could see dozens of feet below—a patchwork of trees, fields of millet, and even a narrow path winding through the landscape. By around 9 a.m., as we continued along the road, we encountered Mr. Wu Zhihui① riding in a jiawo② (a type of mule-drawn sedan chair). He was returning from Hunyuan at that very moment. Hearing from others, we learned that Mr. Wu had spent the entire day exploring Mount Hengshan but hadn’t stayed overnight anywhere on the mountain. We crossed the river once more and arrived at the western gate of Hunyuan County by noon. After resting briefly at the Hui Bin Garden③ located right in front of the county government office, we resumed our journey at about 1 p.m. Around 1:30 p.m., our host, whose surname was Zhang, took us on a guided tour of the town. We first visited Yuanjue Temple, which was originally built in the third year of the Zhenglong era of the Jin Dynasty and later renovated during the early Ming Chenghua period. Inside the temple grounds stands a magnificent thirteen-story pagoda. Next, we explored Yong’an Temple, established in the third year of the Yanyou era of the Yuan Dynasty and extensively restored during the Qianlong reign. Just beyond the main hall of Yong’an Temple, we noticed a strikingly imposing military barracks. The grand central hall was particularly awe-inspiring, adorned with two large inscriptions: "Zhuangyan"④, elegantly calligraphed by Duan Shiyuan⑤, and "Hu Xiao Long Yin"⑥, penned by Zhang Ren⑦—each nearly six meters tall. Despite recent conflicts, the temple still bears numerous bullet marks etched into its walls and steps. Beneath these markings lie commemorative steles dating back to the fourth year of the Kangxi era, as well as the 34th and 52nd years of the Qianlong reign. Surrounding the temple are four smaller chapels dedicated to various deities: Galan, White-robed Guanyin, Ksitigarbha, and Frost God. Above each chapel hangs an elegant plaque reading "Chuanfa Zhengzong Zhi Dian," meaning "The Hall of Authentic Transmission of the Dharma." Inside, three exquisite Buddha statues are meticulously crafted, showcasing remarkable artistry. Our next stop was the Li family ancestral shrine in Li Family Lane, which also served as the former family temple of Li Yumei⑧, the renowned River Governor. Its plaque proudly proclaimed, "Temple of Duke Taibao⑨ and River Commander⑩." By late afternoon, just before 3 p.m., we finally reached the mountain entrance known as Ci Yao Kou⑪. There, an official notice posted at the local government office clearly marked this spot as "Jinlong Kou"⑫—though some modern travelers, referencing Qu Ji’s travelogue⑬, have since dubbed it "Jinlong Yu Kou." To the left of the entrance, a long flight of stone steps once led upward, though sadly, most of them have collapsed, making it impossible to climb any further.

Note:

① Wu Jun Zhihui: Wu Zhihui (1865–1953), later known as Wu Jingheng, was a native of Wujin, Jiangsu Province, and a renowned veteran member of the Kuomintang.

②Jiawo: A traditional mode of transportation in the past, also known as a mule-pulled sedan chair. It consists of two long wooden poles tied to the backs of two mules or donkeys—one at the front and one at the rear—forming a chair-like structure in the middle. Passengers could either sit or lie down inside, while porters accompanied them along the way to tend to the mules, making it easier to navigate rugged mountain paths on long journeys.

③ Hui Bin Garden: Located in what was once the Kyowa Hotel during the Japanese occupation period, it later became a public bathhouse in the 1980s—and today, it’s the spacious courtyard behind the current Antique City building.

Paragraph 4: Duan Shiyuan should be Duan Shida (Da), as "Yuan" was mistakenly written by the author.

⑤ Zhang Ren: Should be Zhang Nuan; "Ren" was mistakenly written by the author.

⑥ Palace Grand Protector: This refers to the Crown Prince's Grand Protector, an official title bestowed posthumously by Jin after Lord Li passed away.

⑦River Governor: An alternate title for the River Canal Superintendent; before his passing, Lord Li served as the River Canal Superintendent of Hedong.

⑧Mule sedan: Carrying pole.

⑨ Wheel-borne: Carried in turns.

⑩ Yu Qiji's Travelogue: Yu Qiji (1888–1957), native of Yangzhou, Jiangsu, was a renowned journalist during the Republic of China era. After traveling to Mount Hengshan in July 1918, he penned "A Record of My Visit to Mount Hengshan," which was published in May 1921 in the journal *New Collection of Travelogues*. In this article, both "Yu's Record" and "Yu's Travelogue" refer to this particular travelogue.

At the second quarter of Shen hour, we arrived at Ciyaoyu, where we ascended the Cliffside Temple, nestled atop Cui Ping Mountain. The mountain lies seven li west of the county town, rising two li high, and is also known as Gao Clan Mountain or Shi Ming Ridge—both names reflecting its rugged, towering presence. It’s here that the You River originates, making this spot the "Gateway to North Yue." The cliff plunges sheerly downward for over 300 zhang, rising vertically as if carved by divine hands. To anchor the structure, wooden pegs were driven into the rock face, supporting the soaring pavilions that seem to defy gravity. With tiered eaves and precarious stairways, the temple appears to hover mid-air, seamlessly blending into the landscape—a masterpiece that rivals a painter’s brushstroke, evoking the serene abode of immortals. Below, the You River flows vigorously, its waters converging in a thunderous roar that never ceases, echoing endlessly throughout the day. On the cliff face, inscriptions include poems by Liu Daoxian and Zheng Luo (though records suggest Li Cai and Fan Shi might also have contributed; unfortunately, these works remain unseen). Further up stands the Chunyang Hall, dedicated to the Three Miao Immortals, its plaque inscribed with the words "Fa Yun Jueling," calligraphed by Zhang Chongde. Higher still, a Buddha shrine awaits, adorned with carvings dating back to the 16th year of the Dading era and again in the 2nd year of the Tianqi reign, created by Li Gao. Beyond that lies the "Zhanxi Cloud Pavilion," whose plaque was personally penned by Bai Zhong, the imperial overseer of the Imperial Stables during the Wanli period. This hall honors Guanyin, though it also houses offerings to both Buddhist deities and Taoist immortals—typical of such sacred spaces. In our hurried exploration, we didn’t have time to inquire about the nearby Li Taibai Shrine or locate any accompanying inscriptions. Finally, traveling southwestward from Ciyaoyu for another thirty li brings us to "Tianci Chanlin"—but alas, we’re left wondering whether this ancient Zen monastery still exists today.

At the beginning of You hour, passing through Yun Ge and Hongqiao Bridge, you’ll notice stone caves measuring roughly two feet square—dozens of them, evenly distributed on both walls. These are the remnants of an ancient structure. According to the local gazetteer: "Two narrow gorges were carved with holes, spanning them with massive beams, upon which a grand pavilion was built as a strategic stronghold guarding the pass—a site truly deserving its reputation as a natural fortress." However, Yang Shucheng’s "Record of Ascending Mount Hengshan" suggests that this location might have been one of the three key defensive points during the early Song Dynasty—but whether it was directly associated with Yang Ye remains unverified and thus not entirely reliable. Further ahead, near the mountain’s edge, stands the Old Master Temple, dedicated to Guan Hou. Above it lie the Arhat Cave and the Bodhidharma Cave, though we haven’t yet reached them.

At 2:08 PM, we arrived at the mountain gate, marking the trailhead into the mountains. In the travelogue②, this path is described as the "Descent," though in reality it’s a gentle upward slope. At the top of the slope stands the Dragon King Temple, currently undergoing restoration by local artisans. Climbing the stone steps leads to a grand archway inscribed with the words "Divine Power Aiding Heavenly Fortune" and "Barrier Guarding Yan and Jin"—both erected during the Guangxu era and the early years of the Republic of China. Above the gate is the plaque reading "Hengshan Mountain," calligraphed by Liu Fu in the 16th year of the Hongzhi reign. Below this, a straight stele proudly declares, "The Number One Mountain North of the Pass." Inside the gate lies the Three Saints Palace, from which the Step-to-Clouds Path begins. Following this trail along the mountain ridge, one soon discovers that the terrain is rich in coal ash—a common sight here, easily found beneathfoot. By now, dusk was settling in, with the lingering warmth of the setting sun mingling with a refreshing breeze. The autumn grasses glowed a somber green, while towering peaks stretched endlessly into the distance, their jagged outlines softened by layers of rolling hills and scattered boulders. At exactly 3:01 PM, we reached the Dragon King Temple, situated at a place known as Tingzhi Ridge. From there, gazing northward, we beheld a breathtaking panorama of countless temple complexes nestled amidst dense forests. Their crimson walls seemed to blend seamlessly with the surrounding woods, creating an atmosphere reminiscent of Beijing's Western Hills or the serene retreats of Mount Lu and Guling—ideal havens for escaping the summer heat. In the distance, a prominent promontory jutted out—the iconic Zhangguo Ridge, flanked by the even more picturesque Sunset Ridge. Winding along the mountainside, we eventually came upon a quaint Daoist monastery adorned with ornate archways—this was none other than the famed Tiger Mouth Pass. Though we had lingered too long to descend safely before nightfall, we pressed on until we finally reached the official reception pavilion just before dusk. After briefly resting there, we moved on to the Pure Yang Palace to spend the night. The resident Taoist priest, Wei Yuanshan (originally from Shangdeng County), warmly welcomed us. Tradition has it that this very palace once housed a revered stele bearing poems channeled through spirit-writing sessions by the legendary alchemist Lü Zu. Sadly, however, the stele has since been dismantled and repurposed as a step in the nearby Yue Temple—leaving the palace itself devoid of any notable relics or treasures.

Note:

① Zhi: Zhi shu refers to the "Zhou Zhi" or "Shan Zhi"—that is, the various editions of the "Hunyuan Zhou Zhi" and the "Hengshan Mountain Zhi." The following are similarly defined.

② On travelogues: Refers to Yu Qiji's travelogue.

▲ In front of the hall at Chuyang Palace on Mount Hengshan

Illustrations in this article

Excerpted from "Travel Magazine," Volume 10, Issue 1, 1936

On the 18th, it was sunny. Starting at the second moment of the卯 hour, I strolled through the various temples and shrines on the mountain. To the right, just below Pure Yang Palace, lies the Shrine of the Wound God, featuring statues of the deity and his consort—this area also serves as the Mountain God Temple. Ascending further up the slope brings you to Bi Xia Palace, better known as the Goddess Temple, as noted in the records. Nine Heavens Palace , inscribed in the ninth year of the Republic of China by Fang Keyou. The deities enshrined here include Jinling Holy Mother, Goddess Nüwa, and Nine Heavens Xuan Nu. To the left stands the Great Compassion Pavilion, dedicated to these same gods; its plaque was calligraphed by Zhang Zongru in the year Xinyou. Adjacent to it is the Lingyun Pavilion, an exquisitely crafted structure perfect for enjoying panoramic views. Inside the pavilion lies the "Monument Inscribing the Renovation of Hengshan Mountain’s Niangniang Temple," penned by Zhao Guoliang and calligraphed by Li Yutian. Both the pavilion and its two side wings offer accommodations for visitors. In front of the temple rises the Bell Tower, while behind it lies the Jade Emperor Cave, situated to the right of the main hall. Ascending from the Chunyang Palace on its left-hand side leads to the Taiyi Heavenly Lord Temple, perched atop the Chunyang Palace itself. Further eastward from there is the Wenchang Temple, with the Guan Sheng Temple nestled to its left. The walls of this temple are adorned with vivid paintings depicting tales of Guan Yu, accompanied by statues of his loyal followers—Guan Ping, Zhou Cang, Ma Liang, Ma Dai, Wang Fu, Liao Hua, Mi Zhu, Zhao Yun, Yi Ji, and Xiang Lang. The inscription "Record of the Renovation of Hengshan Mountain Temple" was written in the tenth year of the Xianfeng reign by Magistrate Li Zhenwei. To the east of this complex stands the Linggong Temple, and higher still lies the Yue Temple. Outside the temple gate stands the Golden Rooster Stone, intricately carved into the shape of a rooster. Legend has it that when one strikes the stone from the opposite hillside, it emits a clear, resonant sound resembling a rooster's crow—a feature reflected in the temple's name, "Chongling," though originally known as Xuanling Palace, later renamed to avoid potential taboos. At the center of the temple grounds hangs a grand, imperial plaque reading "North Pillar of Humanity and Heaven." Surrounding this central monument are four monumental steles: 1. The stele erected in the 18th year of the Shunzhi reign by Magistrate Zhang Chongde, commemorating the renovation of the Hengshan Mountain Temple. This stele is renowned for its elegant parallel prose style, comprising 3,708 characters, many of which employ archaic or obscure vocabulary. Alongside it is engraved a poem composed by Feng Minchang in the Dingwei year of the Qianlong reign. 2. In the eighth year of the Republic of China, Zhang Zhaosong of Hepu added his own inscription beneath the original text. Unfortunately, the stone used for this addition was coated in cinnabar, making it relatively soft and easy to carve. 3. The stele recording the renovation of the Hengshan Mountain Temple during the 24th year of the Jiaqing reign, authored by Magistrate Sun Dasha. 4. The stele documenting the restoration of the North Sect’s Hengyue Temple, signed jointly by Magistrates Wang Zhi and others in the seventh year of the Daoguang reign. Finally, the stele detailing the latest renovation of the Yue Temple, completed in the 22nd year of the Republic of China, was penned by Zhao Guoliang and calligraphed by Li Yingzi. Upon entering the temple, one encounters 93 stone steps (though historical records mention either 98 or 108 steps, neither of which is accurate). These steps lead to what is known as the South Heaven Gate. To the left stands the Azure Dragon Hall, while the White Tiger Hall resides on the right. Flanking these halls are towering Chinese juniper trees. At the heart of the temple complex, the main hall proudly displays a plaque reading "Hall of True Primordiality," dedicated to Beiyue Yuyan Yuanwu Zhenjun, the supreme deity enshrined within. Above the altar hangs an imperial plaque bestowed by the Qing emperor, bearing the inscription "May Its Influence Last Eternally." Inside the hall, two magnificent dragon-carved pillars stand tall, each adorned with intricate depictions of mythical creatures. Behind them, four serene statues of civil officials face inward, while four imposing martial figures guard the outer corners. Before the main altar rests a majestic bronze cauldron, recently completed just four years prior. This cauldron, aptly named "Longquan Guan," serves as both a symbolic centerpiece and a testament to the temple's enduring legacy. On either side of the hall, rows of ancient stone steles stand in solemn silence—twenty-nine in total, all bearing imperial decrees from various Qing emperors. Among them are inscriptions from the Kangxi era (specifically years 5, 24, 36, 42, 52, and 58), the Yongzheng era (year 1), the Qianlong era (years 13, 14, 20, 24, 27, and 53), the Jiaqing era (years 1, 5, 14, and 24), the Daoguang era (years 1, 9, 16, and 26), the Xianfeng era (years 2 and 10), the Tongzhi era (years 1 and 4), and the Guangxu era (years 1, 16, 21, 29, and 31). Sadly, one or two of these steles remain partially hidden from view. (It’s worth noting that no Ming-era imperial decrees are preserved here; thus, Zhang Zhaosong’s claim in his travelogue—that the temple houses steles from every Qing emperor—is inaccurate.) Nearby, another stele catches the eye, featuring calligraphy in the distinctive style of Wang Xun from the Kangxi period’s wuxu year. This stele pays tribute to Wang Xiansheng, the author’s father, through four elegantly rhymed couplets celebrating the sacred mountains of Hengshan, their profound cultural significance, and their timeless allure. Along the temple’s perimeter, ornate wooden pillars support the eaves, each bearing poetic couplets composed by Ruan Ziqian during the Guangxu period’s renchen year. One of these verses reads: "Amidst Hengshan’s ancient towns, where the Central Plains meet, Only our holy dynasty ensures peace—no more war, no more cattle roaming free, For three millennia, our teachings have flourished far and wide. Beneath the six stars of Wenchang aligned with the Big Dipper above, True talents emerge like dragons and tigers, their brilliance piercing through nine heavens." Another verse continues: "As the moon ascends high in the sky, inviting us to revisit the glorious past, We recall with fondness how Guolao mastered the mysteries of the universe, And how the legendary immortal once carried wine across the heavens. Yet now, as clouds part to reveal the path before us, We pray that scholars may spread their wisdom far and wide, Never letting down the promise of spring blossoms or autumn breezes."

From here, ascend to the left for over a hundred steps, and you'll reach the site of the former Zhenyi Terrace, atop which lies Zizhiyu Valley. Continuing eastward, cross the Stone Beam—historically described as a "flying bridge" constructed from horizontal wooden beams spanning twenty *wu*; today, it has been replaced by a stone path, though still not particularly narrow. Climbing up the stone steps for several dozen paces will lead you to the old temple. This ancient temple was originally built in the first year of Taiyan during the reign of Emperor Taowu of the Northern Wei Dynasty. Over time, it underwent four major renovations during the Tang, Jin, Yuan, and Ming dynasties. In the 14th year of Hongzhi, the temple was finally rebuilt into Yue Temple on the sunny side of Zhongfeng Peak, designated as the "Chaodian" (Hall of Morning Worship), while this area became the temple's sleeping quarters. The temple consists of three bays situated at the foot of the peak, though it isn't very spacious. Inside, there’s a reclining stele inscribed by Zhang Shuyu during the Qianlong era, along with two other steles, each engraved with poems accompanied by explanatory notes. This path once led to the site of the old floating bridge, historically known as Floating Bridge Rock. Perched atop the rock is an inscription carved by Cui Yiyuan in the fourth year of Wanli, bearing the words "Road Connects to Heavenly Avenue," and another by Song Wang Xianchen, reading "Thousands of Rocks Compete in Splendor, Ten Thousand Valleys Vying for Flow." On the cliff face, you’ll find an inscription titled "Liquan at the Foot of the Mountain Reflects on Hengshan," alongside a commemorative record penned by Wang Xiyao, the Vice-Prefect of the region, in the 45th year of Wanli. Above this, in the same year, Kong Guangtao from Nanhai left his own inscription during the 12th year of Tongzhi. Nearby, Li Zongxue composed an eight-style poem in the ninth year of Jiajing, complemented by the characters "Gongchen," meaning "Guardian of the Heavens." The main hall bears the plaque "Tianyibao Hall," dedicated to the deity and its consort, adorned with an additional plaque from the 13th year of Yongzheng, inscribed with "Diji Tianxu" ("Earth's Ultimate Celestial Pivot"). Within the hall, four wooden cabinets once housed classic texts, though most have since been taken away by visitors. During the Jiaqing period, paper scrolls written by Daoist practitioners were still preserved. To the left lies Hanyuan Cave, commemorated in the sixth year of Wanli by Zheng Luo, then Inspector-General overseeing the region, along with a detailed account penned by Huang Yingkun, also an Inspector-General, titled "Record of Restoring Tianqiao Cave on Mount Hengshan." (Note: The records mistakenly interchange the names of Zheng and Huang.) Additionally, in the 35th year of Wanli, there’s the "Record of Reverence and Remembrance at Beiyue Temple." At the cave entrance hangs a plaque reading "Fuhuan Tianqiao," inscribed by Huang Yingkun. According to historical records, "the depth remains immeasurable, with cold seeping deep into one's bones; unfortunately, the interior has now been sealed shut, allowing passage for only two or three people at most." Outside the cave, two more stelae remain—both dating back to the Kangxi era (the first, from the sixth year, commemorates the abolition of outdated local regulations; the second, from the 21st year, documents the establishment of the annual wax offering ceremony). The cliff face is densely covered with intricate carvings, many of which are so weathered that they’re nearly illegible. Among them stands an elegiac poem dedicated to Mount Hengshan, composed by Zhang Shuling, the magistrate of Hunyuan, in the third year of Wanli. Continuing upward on the right-hand side, you’ll encounter a naturally formed, deep yet shallow stone hollow—commonly referred to by locals as the "Flying Stone Cave" (though Zhang’s account incorrectly places it within Tongyuan Valley). On the cave wall, two poems about Mount Hengshan penned by Wang Yu during the Dingmao year of the Tianqi era are inscribed, alongside a commemorative stele from the 30th year of Kangxi, featuring calligraphy by Hu Rujie. Interestingly, both the original records and modern accounts place these caves and hollows inside the temple grounds—yet today, they’ve clearly shifted outside, leaving their exact locations uncertain. Higher up, nestled against the cliffside, stands a small, makeshift shrine, likely dedicated to the Goddess of Earth. Adjacent to it is a stele from the seventh year of Hongzhi, authored by Lüzhen and titled "Ancient Record of Beiyue Flying Stone Cave in Hunyuan," with calligraphy by Dong Xi. To the left of the old temple, sheer cliffs rise abruptly, crowned by three large, boldly carved characters reading "Yide Peak." However, the character "Feng" appears distorted from afar, resembling instead the word "Jiang." On the ground floor below, a cursive inscription titled "Xuanque Poetry Draft" is partially legible, though its authenticity remains uncertain—it may well be the work of Liu Qinsun, according to historical records. Above this, a plaque reads "Embracing Boundless Horizons" (though the signboard actually says "Let My Embrace Run Wild," a significant misinterpretation). Unfortunately, there’s no staircase leading to the upper level; access is possible only by climbing around the back of the cliff. Perched atop the building is a plaque from the 50th year of Kangxi, bearing the inscription "Layered Peaks, Dyed in Verdant Splendor"—a structure locally known as the "Makeup Tower," a name that defies explanation. Outside the tower, an inscription from the 19th year of Jiajing by Hu Zongxian can still be seen, alongside a poem by Xie Huai titled "Visiting Beiyue Temple in Early Autumn," part of a series of four verses. Historical records suggest this poem was originally displayed at the Floating Bridge Pavilion—but given its current location, it seems more likely that this refers to the structure we’re examining here. Further up the cliff face, another inscription from the 20th year of Wuxin, penned by Wu Xin'an, catches the eye, alongside a poem by Bao Jiwen from the fifth year of Zhengde. Finally, to the west of the old temple, perched high above the cliff edge, looms a massive, weathered character reading "Baiyun Lingxue"—the "Cave of White Cloud Spirit," a site that, regrettably, remains off-limits to climbers.

Note:

① Zheng Luo Ji: Refers to "Huan Yuan Dong Ji," written by Zheng Luo.

② Jin La Hui Yin: Refers to the Jin La Hui Yin Stele.

Take a short rest. At exactly noon, head west past the Nine Heavens Palace and the Jade Emperor Cave. Unfortunately, neither the famed Cui Xue Pavilion nor the Wangxian Pavilion can be traced today. Arriving at the Kui Xing Tower, perched atop the mountain peak with panoramic views of the county town below, the tower itself is octagonal in shape, built against the mountainside. Scattered among the sparse residential areas, a serene pond reflects the surrounding landscape like a mirror. To the east, the Yingzhou Pagoda appears almost within arm's reach. From here, a narrow path leads directly back toward the town, offering a quicker route that covers roughly ten li. Returning along the original trail, climb upward on the left side of the Niangniang Temple, eventually reaching the Yue Temple. There, briefly exchange greetings with the Taoist priest Zhang Yuanqing before purchasing his detailed map of the area to guide your journey. From behind the temple, continue ascending into the mountains, where you’ll soon arrive at Zhenyi Terrace and Zizhi Valley—but not quite yet. At 11 o’clock, arrange for a local guide to lead you westward to Qinqi Terrace, perched high atop the mountain ridge. Beneath the terrace looms a massive, towering boulder, its jagged cracks seemingly defying gravity as it braces precariously against sheer cliffs—yet somehow, you manage to climb up! Atop the terrace lies a flat, expansive rock surface, perfect for sketching—or perhaps even playing a game of chess, though this particular "chessboard" isn’t the traditional Go board but rather a unique, ancient-style game resembling Chinese chess. Looking down from the terrace, you can gaze into Tongyuan Valley, legend has it, the very spot where Zhang Guo once refined elixirs of immortality. At the base of the cliff, inscriptions from 1935—including names like Mo Dehui—are etched into the rock, alongside calligraphic phrases such as "Round and Majestic," penned by Chen Xingya, and "Great Permanence Brings Tranquility," crafted by Mo Songsen.

Shortly afterward, the path turned eastward, leading to the Huixian Mansion, whose name was inscribed on the cliff face. Inside the grand hall, deities of the immortals were enshrined, with a total of twenty-four sculpted statues—identified by the guide as the eight celestial beings from the Upper, Middle, and Lower Caves. Above the entrance hung a plaque reading "Gazing Southward at the Four Sacred Peaks," calligraphed by Huang Zhao in the Gengxu year of the Qianlong reign. On the northern rock wall stood an ancient stele bearing a poem by Fang Daqi from the Dingyou year of the Wanli era, alongside another poem composed by Zhu Xiuting during his ascent of the mountain in the Gengxu year of the Qianlong reign. Nearby was Zhu Xiudu, who later became the magistrate of Guangling County under Emperor Jiaqing's Zhamao year. To the left stood the Kuixing Pavilion, dedicated to the Jade Emperor, with an imperial stele pavilion (historically known as the Wanshou Pavilion) positioned slightly further left, housing a monument inscribed with the words "May Its Influence Last Forever." To the north of this area lay Jixian Cave, built atop what had once been the mansion's foundation. High above the northern cliff face loomed a colossal character—"Kunlun Shoupai"—carved by Wu Dingyan during the Liao Dynasty; this inscription is widely regarded as one of the oldest surviving examples of its kind.

At 12:30 p.m., we began our walk around the Yue Temple, pausing briefly before heading to the Erlang Temple, which stands tallest among all the shrines. Changyun mentioned that one could ascend to the mountaintop from here at the right moment, but we decided not to venture further, instead returning once again to the Huixian Mansion and Longquan Guan. By 12:45 p.m., I made my way alone to the sleeping quarters, where I sat, lay down, and leisurely admired the surroundings while carefully brushing away moss to read the inscriptions. From there, I continued toward the Jieguan Pavilion, outside which stood the "Monument Commemorating the Reconstruction of the North and South Yue Temples," inscribed in 13th-year Hongwu-era calligraphy by Zheng Yunlao. The script was executed in the Northern Wei style, exceptionally elegant—though I couldn’t help but wonder if it seemed somewhat too modern for such an ancient site. (Before this monument stood another, the "Monument on Abolishing Outdated Practices.") To the right lies Liyi Spring, locally known as Xuanwu Well or Tai Xuan Spring. It features a unique dual-source system, with water tasting sweet on one side and bitter on the other; today, villagers often draw their drinking water directly from here. (According to the old "Hengshan Mountain Record," these two springs—"the Hidden Dragon Spring"—are located just about a foot apart, one sweet, the other bitter. However, this description seems inconsistent with the actual location near Tongyuan Valley.) Above the spring, the plaque was inscribed in 1790 by Huang Zhao during the Qianlong reign, while a later plaque titled "Li Quan Pavilion" was erected in 1884 along Beishuncheng Street during the Guangxu era. The pavilion’s surrounding corridors are adorned with numerous poetic steles, bearing the works of notable figures such as Liu Shiwei, Wu Yan, Zheng Luo, Xiong Mingcheng, Gui Jingshun, Li Shuchun (in 1765), and Li Tao. Next, we visited the main hall, Bai Xuguang Temple, dedicated to Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, the Ten Kings, and their two judges—commonly referred to as the "Ten Kings Hall." In front of the hall stands the Horse God Shrine, flanked by intricately carved statues depicting riders leading their horses. Before the shrine, an ornate archway proudly bears the inscriptions "North Yue Hengzong" and "Eternal Foundation of Ji Province." At 1:15 p.m., Changyun and the others started descending. They remarked that the summit of Mount Yue is devoid of towering trees or elaborate stone monuments, though the guidebook claimed it rises a thousand feet above sea level. Instead, the landscape is dominated by low-lying pine bushes intertwined with wild vines, interspersed with clusters of weathered yellow stones—a sight that indeed aligns closely with their observations. Standing barefoot under the crisp mountain breeze, munching happily on a freshly sliced melon—it truly felt like a moment of pure joy! When asked about the famed Stone Grease Map and the breathtaking views from Zanyungang Ridge, they admitted they hadn’t had the chance to explore those spots yet. Sadly, even the site of Cui Xue Pavilion remains completely untraceable. Later, reading through the travel notes of a recent visitor, Jiang Weiqiao①, I learned that the mountain stretches from its base all the way to the summit, rising an impressive 1,720 *chi* higher than the surrounding plains—equivalent to roughly 5,160 Chinese feet. As dusk approached, we enjoyed our afternoon meal. By 6:00 p.m., we resumed our journey to the Qin-Qi Terrace, where Changyun climbed up for another look. Afterward, we returned to Longquan Guan, following the cliffside eastward until we reached Purple Mist Cave, perched high on the eastern precipice. Unfortunately, this cave wasn’t part of our planned route, so we didn’t make it there after all. Not long after, we arrived at Yan Dao Cave, though work on completing its restoration remained unfinished. Continuing onward, we then came across Wei Cave, home to a striking statue of a Taoist guardian deity. Nearby, a stone tablet dated to the 16th year of the Kangxi reign commemorates the establishment of Yuhua Hall by officials including Xuan Chengyi. The inscription credits the Taoist priest Qingquan, also known as De Yi—an allusion to the nearby De Yi Hermitage. Interestingly, the local "Hengshan Mountain Record" mistakenly identifies "Wei" as "Wei," suggesting either a clerical error or perhaps deliberate misdirection. (It’s particularly amusing how some locals even refer to the temple as "Weidao Temple," adding another layer of confusion!) To the left of the cave entrance sits a small niche dedicated to a figure named Geng Gu, though her identity remains a mystery. Our path, carved directly into the mountainside, eventually comes to an abrupt end. By 7:15 p.m., we retraced our steps back to Xiaoyangling Pass, where we paused to watch the mesmerizing spectacle of the setting sun. Positioned on the western side of the ridge, the view perfectly framed the mountain’s dramatic silhouette, making it the ideal vantage point to soak in the golden hues of the evening glow. Finally, at 9:15 p.m., we settled down for dinner, followed by a peaceful night’s rest by 10:15 p.m.

Note:

① Jiang Weiqiao's Travelogue: Jiang Weiqiao (1872–1958), a native of Wujin, Jiangsu Province, was a renowned educator in modern times. In September 1918, he traveled to Hengshan Mountain and penned "Jiyou at Hengshan Mountain," which was published in the "New Collection of Travelogues" in August 1928.

On the 19th, the weather was clear. We departed early at around 6 a.m., bidding farewell to Yuanshan. At about 9:15 a.m., I began walking ahead of the palanquin, leaning on my walking stick. Along the roadside, there stood a stone cliff adorned with an inscription in seal script that remained indecipherable. Only the words "□ Hua Gui Mao Jingzhong" nearby could be faintly made out. As we walked, we noticed shallow depressions on either side of the path—marks resembling handprints and even donkey tracks, which local villagers believe were left behind when Zhang Guolao accidentally fell from his donkey during a legendary journey. Further up the cliff, two more characters in ancient seal script were partially visible; notably, the upper pair clearly read "Da Ming." By noon, we reached the Tiger Wind Pass, where two towering stone monuments stood against the mountain backdrop. One, erected in the 17th year of the Wanli era, bore the inscription "Hunyuan Prefecture Community Donates Tea to the Clear Spring," while the other, inscribed in the 2nd year of the Hongzhi reign by Dong Xi, proudly displayed the character "Jie Shi." Nearby, there was also the Golden Dragon Pass, directly opposite the Tiger Wind Pass. Though some doubted whether this location truly matched the historical account, it had long been associated with the legend. Continuing onward, we arrived at Da Zi Ridge (also known as Da Zi Bend), where large and small characters reading "Heng Zong" were carved into the cliff face. The larger one featured double-outline strokes arranged vertically, while the smaller one was inscribed horizontally. Ahead lay the majestic Zhenuo Temple, perched atop a secluded peak, directly facing the adjacent Longwang Temple below. In the temple courtyard, several well-preserved steles still stood. Among them was the "Beiyue God's Monument Commemorating Divine Grace," erected in the 7th year of the Chenghua reign by Magistrate Guan Zong—a work penned by Bao Kekuan, though the author's name is now missing. Nearby stood another stele from the 5th year of Chenghua, chronicling the reconstruction of the Beiyue Temple in Hunyuan Prefecture, authored by Liu Xu. And then there was the "Monument Recording Rain-Praying Insights," created in the 15th year of Chenghua (Year of Yi Hai) under the supervision of Magistrate Feng Gui, with the text penned by the Taoist scholar Yian Dao Ren. Interestingly, most of the steles from the Yuan and Ming dynasties bore inscriptions signed with the sages' Daoist monikers—something rarely seen elsewhere. (According to historical records, all three steles were supposedly commissioned during the reign of Emperor Wuzong, but this contradicts current evidence. Moreover, the authors listed—Yang Xin, Liu Yu, and Li Min—also seem inconsistent with the actual historical figures.) Finally, at around 9:15 a.m., we boarded the palanquin once again and resumed our journey downhill. The terrain became increasingly rugged, with alternating patches of earth and rock, occasionally revealing layers of coal. The mountain was largely devoid of trees, save for a few sparse groves near what locals call the "Deep Valley of Ten Thousand Pines"—though even those remnants numbered no more than a hundred or so scattered specimens. Instead, the landscape was dominated by vast fields, stretching endlessly across the rolling hills and deep valleys below. By noon, we reached the mountain gate, and after another hour’s walk, we arrived at the village nestled just outside the mountain entrance. Here, nearly a hundred households relied entirely on this remote area for their daily needs.

At exactly 2:15 PM, we dismounted and began our ascent up the mountain, arriving at Daruma Cave. Inside the cave stands a single statue, while the cavern itself spans over ten zhang in width, complete with windows, doors, and even a traditional kang-style bed. Climbing further, we reached Luohan Cave, which overlooks the back of Daruma Cave. This second cave is even larger and houses eighteen statues of arhats. Adjacent to it are two small rooms—fronting the hall dedicated to Weituo, which was recently renovated and officially completed last year. By shortly after noon, we passed by the Old Master Temple and continued onward until we reached Yun Ge Hongqiao, the famous Hanging Temple perched high above the clouds. From there, we headed northward, veering slightly left toward Fufang Temple—but unfortunately, despite our efforts, we couldn’t find Li Bai’s inscription reading "Zhuangguan" (Magnificent View). At exactly 2:15 PM, we arrived at Jinlongkou. By noon sharp, we made our way to the Nangong Gate and the Hengyue Xingong Palace, whose main hall—the Dazhen Hall—is an architectural marvel in its own right, boasting grandeur and splendor. At exactly 12:15 PM, we stopped at Huibin Garden for lunch, where I purchased copies of the *Hunyuan Prefecture Gazetteer* and the *Hengshan Mountain Gazetteer* to cross-reference during our journey. Hunyuan is renowned for its eight scenic attractions: First, the misty rain over Cixia Gorge; second, the pine-scented winds atop the mountain peak; third, the golden hues of sunset reflecting off the cliffs; fourth, the pristine snowfall on Longshan Mountain after a clear sky; fifth, the icy cascades of Yiquan Spring; sixth, the vibrant autumn colors adorning Baiyan Rock; seventh, the serene moonlight shimmering over Shenxi Stream at night; and eighth, the tranquil, cloud-filled vistas of Yuanyu Valley. However, due to our tight schedule, we could only visit half of these breathtaking sites before rushing on. As the afternoon wore on, we noticed that transportation costs had soared—each vehicle now demanded five silver coins, making travel increasingly expensive. By 3:15 PM, we crossed the river once more, stopping along the way at a local farmer’s home to buy some refreshing watermelons. For just one silver coin, we managed to grab six juicy slices—truly a bargain! Finally, as the sun dipped lower in the sky, we took a winding path through Xiaojiagou. By dusk, we reached Erling—a quaint spot where we decided to spend the night, nestled comfortably amid the quiet countryside.

On the morning of the 20th, we rose before dawn, had a light meal, and began packing our belongings. We set off precisely at 2:02 a.m., traveling under the moonlight through the night. By 2:15 a.m., we arrived at Songshuwan. From there, the path descended steeply downhill; we followed a muddy ditch on foot, looking down to catch a glimpse of the trail we’d taken earlier as we made our way back. The mountain valleys were remarkably clear and pristine, though the earthen banks occasionally crumbled, and even the rocks seemed to shift and tumble—evidence of the heavy rainfall from the previous day. By 6:00 a.m., we reached the edge of the mountain. Still wary of continuing along the narrow canyon, we instructed the driver to carefully scout ahead before proceeding. At times, the uphill sections posed significant challenges, with steep slopes that raised concerns about safety. Along the way, we passed a couple of small huts where travelers could rest—and, notably, purchase steamed buns. This mountain range is predominantly composed of earth rather than stone, but in its narrowest sections, water flows through naturally, creating breathtaking "gateways" of cascading streams. By 7:00 a.m., we finally reached Wengchengkou. Just after 8:15 a.m., we crossed the Sanggan River. By noon, we arrived at Lijiagou, still some 50 miles away from our destination. Deciding to stop for a quick meal at a nearby inn, we found none of them occupied—every single one was deserted. We pressed on for another 20 miles, arriving just before 9:00 a.m. at Shangqiao, where we stopped for lunch at Dongsheng Inn. After finishing our meal, we resumed our journey and continued eastward. By 3:45 p.m., we crossed the Shili River, wading through fine sand churned up by the relentless wind, which swirled fiercely into our eyes, stinging our noses and soaking our clothes. As dusk approached, we finally entered Datong’s eastern gate and headed straight toward the railway station. At 9:45 p.m., we boarded the express train back home via the Ping-Sui Railway. Along the way, Station Chief Ning Shufan and Station Master Gao Wenzao came to bid us farewell. Early the next morning—at around 6:00 a.m.—we safely arrived back in Beiping.

▲ The Huixian Mansion on Mount Hengshan

Illustrations in this article

Excerpted from "Travel Magazine," Volume 10, Issue 1, 1936

Although Mount Hengshan was historically a key stronghold of Bingzhou, it has long been neglected and poorly cherished. After Zhao Xiangzi conquered the state of Dai, King Xiao Cheng of Zhao exchanged Fenmen for Pingshu—Pingshu today corresponds to Hunyuan County. During the Han dynasty, Emperor Guangwu abolished Guo County altogether, relocating its officials and residents inland. Later, during the Jin dynasty, Liu Kun even abandoned the area to Dai King Tuoba Yilu. Subsequently, the Later Jin dynasty ceded Yingzhou to the Khitans as a bribe. In the third year of Song Yongxi, the region was briefly recaptured but soon lost again. By the eighth year of Song Xining, the land north of the ridge of Mount Hengshan was ceded to the Liao dynasty. It wasn’t until the Southern Song period, when the Jin dynasty finally overthrew the Liao, that the mountain was finally restored to Chinese territory—only to be reoccupied by the Jin shortly thereafter. Over the centuries following the Yuan dynasty’s fall, the region remained under foreign rule for nearly several hundred years, a period marked by profound cultural decline. As a result, despite the mountain’s breathtaking natural beauty, very few notable historical sites or landmarks remain. Consequently, a full day is usually sufficient to explore all its scenic spots. As for literary figures who have celebrated this place through poetry and prose, the list is surprisingly short: starting from the Tang dynasty with poets like Zheng Fang and Jia Island, we find Yuan Hao-wen from the Jin, followed by Zhao Bingwen and Liu Yin of the Yuan, then Qiao Yu, Yang Wei, Dong Xi, Yang Shucheng, Hu Zongxian, Wang Jiaping, Li Mengyang, and Wang Shizhen of the Ming, and finally Wei Xiangshu, Qu Dajun, Cao Rong, Xu Jisi, Zhu Xiudu, and Li Yuwang of the Qing—and even these names can easily be counted on one hand. When it comes to travelogues about Mount Hengshan, the number remains disappointingly small, limited mainly to works by scholars such as Xu Hongzu, Yang Shucheng, and Wang Xiqi, extending only to more recent writers like Yu, Jiang, and Zhang. This scarcity reflects the mountain’s relative obscurity compared to other famous landscapes, leaving much of its rich history and charm untold for those yet to visit.

Note:

① The Yu, Jiang, Zhang, and other individuals: Refers to Yu Qiji, Jiang Weiqiao, Zhang Zhaosong, and others.

Hengyue Travelogue

"Travel Magazine," Volume 10, Issue 1, 1936

Pages 75 to 83

Proofreading: Xuefang

Editor: Xuelin

About the Author

Guan Genglin (1880–1962), courtesy name Yingren, was born in Nanhai, Guangdong. He passed the imperial examination as a jinshi in the special class of 1904 during the Guangxu reign and went on to become a renowned modern poet, scholar, lyricist, industrialist, and educator. He was also a key figure in promoting China’s railway development. After the establishment of the Republic of China, he held various high-ranking positions, including Director of the Jinghan Railway Bureau, Director-General of the Road Administration Division at the Ministry of Communications, President of Beijing Jiaotong University, and Director of the Pinghan Railway Bureau. In 1956, he was appointed as a member of the Central Academy of Literature and History Research. Notably, his son, Guan Zhaoye, was a distinguished student of the celebrated couple Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin, and later became an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. He is the author of… "A Record of the School Inspection Trip to the East" "Lectures on the History of Chinese Railways," "The Present and Future of the Beijing-Hankou Railway," "Yingtan," "Jiyuan Poetry Collection," and more.

Keywords:

Related News